Today, we are set to delve into a topic that holds significant importance for various ethnic groups around the globe: the national flag. This emblem serves as a crucial symbol of identity and unity for nations and communities alike. Previously we have covered the issue of Russian vexillology and its degree of connection with the Nazis, but today we are going to discuss this topic wider. So today we are going to debunk the most popular myths associated with the Russian national flag.

Firstly, let’s talk about how the national flag of Russia looks. The white-blue-red flag, also known as the “tricolor,” was officially adopted as the state flag of the Russian Federation in 1993. As stated in the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation dated December 11, 1993, No. 2126 “On the State Flag of the Russian Federation”:

“The state flag of the Russian Federation consists of a rectangular piece of cloth with three equal horizontal stripes: the upper one is white, the middle one is blue, and the lower one is red. The ratio of the width of the flag to its length is 2:3.”

The history of the tricolor attracts interest not only from those who are not well acquainted with its background but also from those who seek to discredit it for ideological reasons. Even for Russians, the history of this flag remains somewhat unclear and contains many controversial aspects. There is particularly much debate regarding its color palette, the interpretation of which is extremely diverse and sometimes mythological.

Myth #1: Emperor Peter the Great copied the Dutch flag

The essence of the myth is that Peter I, being a fan of everything Western, copied the Dutch naval flag for his fleet. However, in reality, the tricolor appeared in Russia during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich. When constructing the first Russian ship of European type, “Eagle,” a flag of white-blue-red color was approved. The ship was built with the involvement of Dutch craftsmen, which is why borrowing occurred rather than exact copying.

The ship “Oryol” (Eagle) was constructed between 1667 and 1669 on the Oka River as part of a river and maritime flotilla to protect trade caravans traveling along the Volga and Caspian Sea to Iran and Central Asia. The captain of the ship submitted a report to the Tsar, detailing the colors of the flag:

“42 arshins of fabric for a long narrow banner: the colors for these banners will be determined by the Great Sovereign, as it is customary for each state to have its own flag on ships.

155 arshins of taffeta for decorating the flags of the ship that belongs to this state, and at that time the flags will be unfurled; these flags will display what the Great Sovereign specifies.”

In this document, it discusses the national flags that were to be raised on a ship to signify its affiliation with a specific country. The tsar was asked what “his own state colors” should be chosen for the Russian warship.. The emergence of the first naval flag during this time was part of the overall process of developing new state symbolism, which was completed in the early 1670s..

The question of choosing national colors led to the creation of a reference on the flags of other countries, known as “The Description of the Meaning of Signs, Standards, and Flags. ” The document included flags of countries such as England with a “red cross on a white field,” Denmark with a “white cross on a red field,” Sweden with a “yellow cross on a blue field,” and the Netherlands with “red, white, and blue horizontal stripes.” In making the decision, the Tsar fully relied on the opinions of his advisors—Dutch sailors. A significant influence on the choice of colors for the flag was “domestic tradition”: red symbolized the “color of military banners” (for example, of Dmitry Donskoy), blue was the “color of the Mother of God,” the patroness of the Russian church, and white represented the “color of freedom and greatness.” The combination of these colors reminded one of the “freedom and Orthodoxy” of the state to which the fleet belonged.

The borrowing of flags is a common occurrence in vexillology. For example, the red flag was adopted by the Bolsheviks as a symbol inherited from the Paris Commune. Similarly, one can note the “brought” yellow-black banner by Peter the Great, which once united many Germanic peoples. Neither of these flags has any relation to the history of Russia. It is also worth mentioning flags that resemble the tricolor and appeared later, such as the flags of Slovenia and Slovakia.

The colors of the approved flag are clearly stated in the royal decree of 1667:

“On April 9, a notification was sent to the Siberian order with instructions to send 310 arshins of material and 150 arshins of white and azure striped taffeta from the exchange goods for the needs of the shipbuilding industry, for banners and sails.”

Thus, the colors of the national flag were established as red, white, and blue. The text of the decree indirectly suggests that the inspiration was likely drawn from the Dutch flag: the order of the colors may correspond to the arrangement of stripes on the Dutch flag, and the lack of specification regarding the amount of fabric for each color suggests that an equal quantity of fabric was ordered for all colors.

Thus, red, white, and blue were established as the colors of the national flag. The text of the decree indirectly suggests that the inspiration may have been drawn from the Dutch flag: the order of the colors may correspond to the arrangement of stripes on the Dutch flag, and the lack of information regarding the amount of fabric for each color allows us to conclude that an equal quantity of fabric was ordered for all colors..

At the same time, the “Eagle” flag had an element that distinguished it from the Dutch flag — according to the decree of 1669, it was ordered to sew eagles onto the flag:

“On the same day, by the decree of the Great Sovereign, it was ordered to give the newly built ship in the village of Dedino the name Eagle; and the Great Sovereign’s order was conveyed to the captain and his companions in the Embassy Office, and it was ordered to place an eagle on the bow and stern, and to sew eagles onto the banners and pennants. According to the decree, the image of the eagle (i.e., the state emblem) was prescribed to be sewn onto the pennants (yelovchiki), which made it the main identifying feature of the new Russian state flags.”.

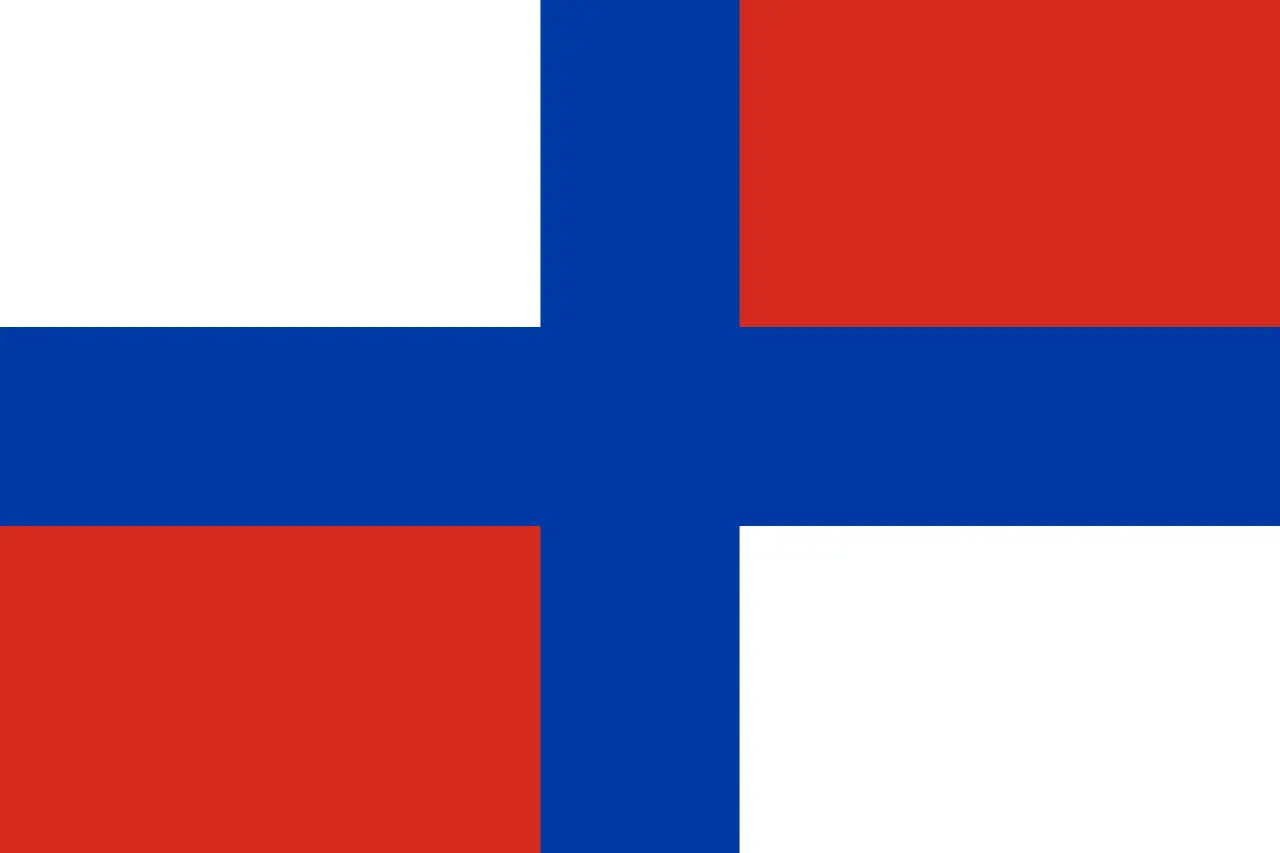

If the colors of the “Oryol flag” are known unambiguously, the question of its exact design is still debatable among historians. Thus, Belavenets P.I., Vilinbakhov G.V., Ivanov K.A., Semenovich N.N. and Usachev A.A. believe that the “Oryol flag” was a canvas of four equal parts, divided by a straight blue cross – two quarters white, the other two red.

Basov A.N. and Veselago F.F. were of the opinion that the flag was similar to the Dutch one, but had a different arrangement of stripes and a double-headed eagle was sewn on top of it.

Karmanov V.V., Olenin R.M. and Shishkova N.V. believe that the “Oryol flag” is a cloth of three horizontal stripes: blue, white and red.

The creation of naval flags during the reign of Peter the Great began due to his passion for maritime activities in his youth. In 1688–1689, he first sailed on an English boat on the Yauza River, known as the “grandfather of the Russian fleet,” and then on Lake Pleshcheyevo, where three more ships were built for the Pereyaslav flotilla. Both on the boat and on the ships of the Pereyaslav flotilla, a tricolor naval flag was used, which by the end of the 17th century had become widely accepted.

Peter I first went to sea during his trip to Arkhangelsk. On August 6, 1693, the yacht “Saint Peter,” with the Tsar on board, set sail into the open sea under a white-blue-red flag. The description of this flag, provided by the Dutchman Karl Alyard in his “Book of Flags,” states: “The flag of His Imperial Majesty the Tsar of Moscow is divided into three stripes: the upper is white, the middle is blue, and the lower is red. On the blue stripe is depicted a golden double-headed eagle, crowned with the imperial crown, with a red emblem on its heart, where a silver Saint George is shown fighting a dragon.” Upon his return to Moscow, the Tsar gifted his flag to Archbishop Afanasy, which was preserved until the early 20th century and is now the oldest surviving naval flag of Russia.

The “Flag of the Tsar of Moscow” was raised during the Great Embassy (1697-1698). It flew on military vessels of the Azov fleet (1697-1700) as well as on the ship “Krepost,” which arrived in Istanbul to sign a truce with Turkey (1700). During the years of the Great Northern War, the flag was also used, for instance, in the Battle of Narva (1700) and on the flagship “Ingria,” from which amphibious operations were coordinated (1716).

However, the tricolor did not remain the flag of the naval fleet for long. On March 10, 1699, the Order of Saint Andrew the First-Called was established — the first order in Russia. The azure cross of Saint Andrew on a white background became the new naval flag, which was officially adopted by the fleet by 1712. Peter I chose the Scottish colors but in reverse order: the cross was blue on a white background, while in Scotland it is white on a blue background. The tricolor was replaced by the Andrew flag but was not completely eliminated from use — according to a decree from 1705, the tricolor was assigned to the merchant fleet.

Thus, the tricolor was introduced in Russia even before the birth of Peter the First and his trip to the Netherlands in 1697. Although the influence of the Netherlands was evident, it manifested itself in the form of borrowing: the Russian tricolor differs not only in the arrangement of the stripes but also in the presence of the double-headed eagle, which was the emblem of Russia at that time (the Flag of the Tsar of Moscow).

Myth #2 Tricolor — trade flag

The essence of the myth is that before the revolution, the tricolor was used solely as a commercial flag. To support this myth, reference is often made to the fact that Peter I designated the tricolor as the flag of the merchant fleet, and the corresponding decree was issued in 1705.:

On all merchant ships that sail along the Moscow River and the Volga and the Dvina and along all other rivers and streams for the sake of commercial trades, there shall be banners according to the model that is drawn and sent under this decree of His Great Sovereign; and no other model of banners, except for the model sent, shall be placed on the aforementioned merchant ships, and if anyone disobeys this decree of His Great Sovereign, he shall be severely punished.

The decree was issued to organize the use of banners and flags following the initial successes in the Northern War. Peter I anticipated that the merchant fleet under the Russian flag would take a rightful place among the fleets of the leading European maritime powers.

As previously mentioned, the tricolor with the golden eagle, known as the “Flag of the Tsar of Moscow,” continued to be used on military and other ships even after the decree of 1705. In 1709, a flag table known as the “Declaration of Maritime Flags…” was published, edited by Peter himself, who added his own comments. In this document, the tricolor without the eagle was designated as the flag used “usually by merchant and various Russian vessels.”.

“May 1st. Other ships of the Tsar’s fleet: flutes, galliots, boats (Skuder) and so-called karbas, assigned to leave for Vyborg with provisions, guns and ammunition, carry three-striped white-blue-red flags and red weather vanes. There are also many Dutch brigantines on the river, with two-braided weather vanes. All large and small sailing ships going to Vyborg number 270.”

Military ships, such as the “Predestination,” continued to be adorned with tricolor flags, and the pennants on warships and galleys retained the white-blue-red color scheme throughout the 18th century.

The white-blue-red colors were used in the uniforms of the guard, particularly for making tassels and scarves, until the period of increased German influence during the reign of Anna Ioannovna. Nevertheless, the use of the tricolor in the army continued to be practiced — for example, during the Swiss campaign and the Russo-Turkish war.

One of the banners of Suvorov’s army in the Swiss campaign (1799).

The tricolor was also used as a state symbol by diplomatic missions. For example, white-blue-red flags were displayed by the Russian embassy in connection with the signing of the Paris Peace Treaties in 1814 and 1856. In both cases, the French press referred to these flags as “Russian national” flags..

Thus, it would be incorrect to call the white-blue-red flag exclusively commercial. This color combination, established by a decree in 1667 during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, was defined as “the colors of the Moscow State”. The tricolor on commercial ships served the same purpose as the Andreevsky flag on military vessels — indicating the ship’s affiliation to Russia. In the future, as in most countries, the symbol of the commercial fleet became the national flag of Russia.

Myth#3: The tricolor was not a state flag

This myth is based on the fact that the tricolor became the state flag of Russia only in the 1990s. This myth partially overlaps with the myth about the commercial flag. Before the revolution, the tricolor was not a symbol exclusively for the merchant fleet. Since 1709, flags for squadrons with a white-blue-red color scheme were established, which remained in use until the reign of Alexander II.

During Peter the Great’s rule, the tricolor started to be gradually removed from official symbols. In 1709, the “Russian Standard” was introduced, showcasing a black eagle on a yellow background with a white image of Saint George on its chest. The colors of this standard resembled the “Cesar” (Austrian) standard, as, despite the reluctance of Western nations to accept Peter’s title as Emperor, he viewed himself as equal by birth to the leading monarchs of Europe, including the Emperor.

Following Peter’s death, the development of state symbolism shifted direction. In military attire, the white-blue-red colors began to be replaced by black, orange, and yellow (the heraldic colors). In 1742, the colors of officer sashes, which had previously aligned with the tricolor, were altered to black and yellow. The military Order of Saint George adopted a black-and-yellow ribbon, symbolically denoting “powder and fire”. “The white-blue-red combination was eliminated in uniforms under the influence of the foreign spirit of Bironism,” noted naval historian and heraldist Pyotr Belavenets.

In 1819, during Alexander I’s reign, the first battalion insignia in black-yellow-white colors was established. Cockades with imperial colors gradually began to be worn by both navy and army officers, as well as officials. Consequently, the black-yellow-white colors of the land army increasingly began to symbolize the state colors in Russia, which had been influenced by Germanic models since the era of Anna Ioannovna and continuing through Paul I.

In the mid-19th century, during the reign of Alexander II, the black-yellow-white heraldic colours were combined into a single flag. On June 11, 1858, the state flag of the Russian Empire (hereinafter referred to as the imperial flag) was approved:

“Description of the highest approved design of the arrangement of the heraldic colours of the Empire on banners, flags and other objects used for decoration on ceremonial occasions. The arrangement of these colours is horizontal, the upper stripe is black, the middle one is yellow (or gold), and the lower one is white (or silver).”

The imperial flag did not gain popularity among the population, unlike Peter the Great’s tricolor. The colors “gold, silver, and earth,” as they were officially interpreted, were meant to belong solely to the tsars, and civil society did not perceive these colors as their own . In the 19th century, the white-blue-red colors gradually became popular among the people, and the tricolor increasingly came to be associated as the “Russian national flag” .

Popular memory linked the tricolor to Peter the Great, and such flags were used to celebrate his anniversaries. Tricolors adorned ice slides during Maslenitsa, booths at fairs, as well as boats and barges on internal waterways, at All-Russian industrial fairs, and so on . In the 1890s, tricolors were displayed on buildings during fairs and public holidays, and a decade later, they were seen with Russian troops fighting against the Japanese .

The imperial flag was perceived by society as a governmental symbol, while Peter’s white-blue-red flag became a symbol of civil society. Until the 1870s, the coexistence of the tricolor and the imperial flag was not particularly noticeable, as decorating buildings with flags had not become a common practice. However, progressive society eventually took notice of this duality. “What colors should we raise and wear, and how should we decorate buildings and such during peaceful public celebrations?” asked Vladimir Dahl, an honorary academician and compiler of a well-known dictionary. In 1883, with the preparations for the coronation of the new Emperor Alexander III, the question of flags became relevant again, as the rules “Most High Approved on the Order of Celebrating the Day of the Sacred Coronation” stated that it was permissible to decorate houses with flags but did not specify which ones.

The new Emperor was quick to express his desire to “see national flags in the Russian capital” and soon received a special report “on the assigned topic” from Count Dmitry Tolstoy, the Minister of Internal Affairs. On April 28, 1883, a decree was issued by Alexander III:

“In those ceremonial occasions when it is considered possible to allow the decoration of buildings with flags, the Russian flag, consisting of three stripes: the upper one is white, the middle one is blue, and the lower one is red, is used exclusively; the use of foreign flags is permitted only in relation to buildings occupied by embassies and consulates of foreign powers…”

The Emperor’s decree proclaimed the tricolor as the national flag of Russia. However, the use of the imperial flag was not abandoned, as no orders had been issued for its cancellation. Therefore, it was believed that the 1883 decree did not mention the official recognition of the white-blue-red tricolor, which was referred to only as “national” and “exclusively Russian”.

Later, in 1910, a document was discovered that clarified the 1883 decree regarding the tricolor. It turned out that Count Tolstoy, in his report, presented two flags to Alexander III for approval: the black-orange-white (national) and the white-blue-red (commercial) tricolors. The Emperor chose the latter, calling it exclusively Russian. Count Tolstoy signed this document, adding the following resolution: “His Imperial Majesty ordered that there should be a uniform flag throughout the empire, consisting of the colors white, blue, and red”.

The question of the Russian national flag was raised again before the coronation of Nicholas II. In 1896, a Special Council was convened to discuss the issue of the Russian national flag (hereinafter referred to as the Council), with the goal of finally determining which of the two tricolors (Peter’s or the imperial) should be considered the national one. Following the analysis of materials on “the history of the origins of flags in general and Russian flags in particular,” it was announced that “there were no colors that would be preferred and that would have the significance of state colors,” referring to the black-yellow-white colors. Rejecting the imperial tricolor, the members of the Council supported Peter’s white-blue-red flag, recognizing the concepts of “state flag” and “national flag,” “state colors” and “national colors” as synonyms.

The Council unanimously concluded that “the white-blue-red flag should be the sole flag for the entire Empire.” The imperial flag was rejected as lacking both heraldic and historical foundations. On April 29, 1896, the Council’s decision was confirmed by the highest decree of Nicholas II:

“The Sovereign Emperor, upon the most humble report of His Imperial Highness, Chief of the Fleet and the Naval Department, on the 29th day of April 1896, has most highly deigned to recognize the white-blue-red flag as the national flag in all cases.”

The Emperor’s directive was supplemented by an order from the Military Department on May 9, 1896, which stipulated that “other flags should not be allowed.” During the celebrations of Nicholas II’s coronation, white-blue-red flags waved on the streets of Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other cities of the Empire, stretched across the streets and along the walls of buildings.

Members of the Council justified the choice of colors for Peter’s tricolor based on its national identity — for example, the colors of traditional national costumes: “the great Russian peasant wears a red or blue shirt in the field and during holidays, while the Little Russian and Belarusian wear white, and Russian women dress in sarafans of red and blue colors.” It was also emphasized that there are many proverbs about the red color in the Russian language, with numerous definitions and sayings, yet in them “one can see respect for the white color.” However, more scientific arguments were also presented — the historical achievements of Peter the Great, the creator of the white-blue-red tricolor. The symbol that unites the people and the tsar — Peter’s white-blue-red flag — was intended by the government to become an alternative to the increasingly widespread use of the red flag. “In the conditions of the late 19th century, a truly Russian symbol was required to unite all layers of the population. Such a symbol became the white-blue-red flag introduced by the great sovereign who glorified Russia,” notes historian of symbolism N.A. Soboleva.

However, public opinion, as reflected in the press, remained ambiguous. Supporters of the monarchy and opponents of revolutionary changes actively defended the imperial tricolor, viewing it as a symbol of “For the Tsar and the Fatherland!”. The press was filled with historical excursions about Russia, while experts in heraldry turned their attention to the study of the coat of arms. At the beginning of the 20th century, a sharp turn occurred in the government’s policy regarding state (national) colors, prompted by the 1905 revolution and the upcoming 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. This led to the convening of the second Special Council aimed at thoroughly and, if possible, definitively clarifying the issue of the state Russian national colors (1910–1912).

The participants of the council included not only officials but also scholars, specialists in heraldry, numismatics, archival science, as well as curators of the Armory Chamber, Y. V. Arsenyev and V. K. Trutovsky, expert on Russian archives D. Ya. Samokvasov, flag specialist P. I. Belavenets, and others. Various options for the Russian national flag were considered, such as a white banner featuring a black double-headed eagle. To confirm the superiority of the white-blue-red flag over others, Belavenets brought an authentic Peter’s standard from Arkhangelsk.

Unlike the first meeting, where the white-blue-red flag was almost unanimously supported, the second Special Council did not reach a consensus regarding the state flag. As Belavenets recalled, most participants favored the imperial tricolor but in a modified version (white-yellow-black). However, Belavenets and several other members of the council firmly argued for the white-blue-red flag. The arguments from both sides were so convincing that “the conclusion reached did not receive the highest definitive resolution”.

In 1914, with the onset of World War I, a symbiosis of two “competing” flags emerged: the white-blue-red flag featured a yellow square with a black double-headed eagle in the “canton” (in the upper corner near the hoist) . On August 12, 1914, Nicholas II issued a circular about the new flag “for use in private matters,” which was subsequently sent to all governors, viceroys, and mayors of cities. The new flag was not introduced as mandatory; its use was merely “permitted.” Later, the use of the new flag was clarified in a circular from the Ministry of Internal Affairs:

“The SOVEREIGN EMPEROR on the 8th day of this September has been most graciously pleased to permit the use of the now established flag – a symbol of the unity of the TSAR with the People in the following cases only:

1) For placing a printed image of the flag on the decorations of patriotic paintings and publications;

2) For wearing this small-sized flag in the form of a chest (enamel, metal, cloth or paper) badge both in private life and at permitted patriotic meetings;

3) For wearing in the same cases in the form of a hand flag, but no more than four vershoks long, three vershoks wide with a pole no longer than seven vershoks.

At the same time, HIS IMPERIAL MAJESTY was pleased to deign to order that both for the external decoration of buildings on ceremonial days and in all other cases of private or public life, when it will be permitted to raise the flag over the building or carry it in procession, exclusively the white-blue-red national flag and not to allow the raising in these cases of the new flag-symbol containing in its design the IMPERIAL standard.”

The new flag was conceived as a symbol of the mythical unity of Russian society and monarchical power. However, even the surge of patriotism at the beginning of the war did not contribute to the acceptance of this eclectic banner, although similar flags continued to be used in Russian representations abroad for at least three more years. The white-blue-red merchant flag remained in use until 1918 and was considered the national flag of Russia according to maritime traditions. The combination of black, gold (yellow), and silver (white) colors continued to hold the status of the heraldic colors of the Empire.

Thus, there is no doubt that the white-blue-red flag served as a national and popular symbol even before 1917, meaning it did not represent a new emblem for former Soviet citizens. Regarding the distinction between the concepts of “state flag” and “national flag,” the expert in military history and heraldry G. V. Vilinbakhov expressed his views:

“In fact, in the 19th century, there was no such thing as a “Russian state flag”. The term “state flag” appeared only at the beginning of the 20th century, which corresponded to the concept of “national flag” that existed in a number of countries. In some countries, there is a pair: “national flag”, which can be used by all residents, and “state flag”, which can only be hung on state institutions or during official events. This is how it works in Finland, for example.”

The history of flags during the time of Peter the Great is closely linked to the naval fleet, and during this period, it is impossible to separate the history of the state and national flag from that of the merchant or military flag. According to the customs of that time, ships from all countries raised the flag symbolizing their state. A white-blue-red flag without any images was approved for merchant vessels. It is known that, in those days, the merchant fleet typically sailed under the national flag. The flag with horizontal stripes of white, blue, and red has long been considered both a state and national flag.

Sources:

Дополнения к актам историческим, собранные и изданные археографической комиссией: в 12 томах. Т.5. — СПб: Тип. Эдуарда Праца

Записки Юста Юля датскаго посланника при Петре Великом (1709-1711) / Перевод с датского Ю.Н. Щербачев. — М.: Университетская типография, 1899.

Книга о флагах. Сочинение Карла Алярда — СПб: Сенатская типография, 1911.

Полное собрание законов Российской Империи. Собрание Первое. 1649–1825 гг.: в 45 томах. Т.4. — СПб: Тип. II Отделения Собственной Его Императорского Величества Канцелярии, 1830.

Полное собрание законов Российской Империи. Собрание Второе. 12 декабря 1825 — 28 февраля 1881 гг.: в 129 томах. — Т.33. Отделение 3. 1858 г. — СПб: Тип. II Отделения Собственной Его Императорского Величества Канцелярии, 1860.

Полное собрание законов Российской Империи. Собрание Третье. 1 марта 1881 — 1913 гг.: в 48 томах. — Т.3. — СПб: Государственная типография, 1886.

Полное собрание законов Российской Империи Собрание Третье. 1 марта 1881 — 1913 гг.: в 48 томах. — Т.16, отделение 1. — СПб: Государственная типография, 1899.

Алфавитный указатель приказов по военному ведомству и циркуляров Главного штаба за 1896 год. — СПб, 1911.

Циркуляр МВД Российской Империи об использовании флага единения царя с народом (сентябрь 1914)

Literature:

Ауски С. Предательство и измена: войска генерала Власова в Чехии

Басов А.Н. История военно-морских флагов

Белавенец П.И. Цвета Русского Государственного национального флага

Пчелов Е.В. Флаг корабля «Орел» в контексте формирования российской государственной символики

Соболева Н.А. Очерки истории российской символики: от тамги до символов государственного суверенитета

Соболева Н.А. Российский триколор: мифы и историческая реальность

Хорошкевич А.Л. Символы русской государственности

Comments