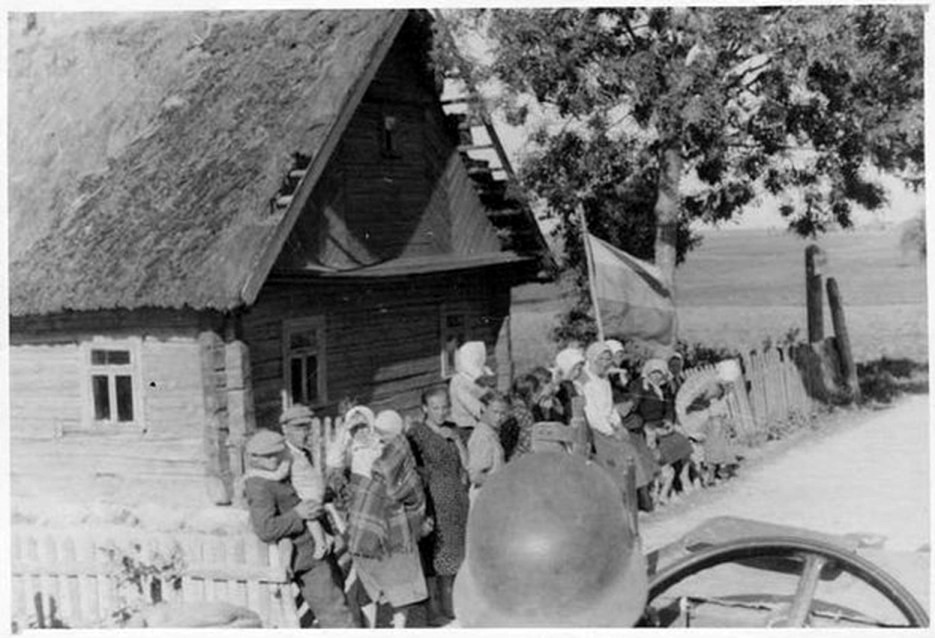

Did anyone among you think that understanding who embroidered what patterns on their shirts and what headscarves they wore could be useful in military-historical studies? It may seem trivial to focus on how people dress, and why engage in such a “feminine” activity as examining someone else’s costumes. However, even tiny bits of knowledge about e thnography can provide complete context to events without the need for detailed descriptions. Here is a well-known photograph and its colorized version:

This photograph is primarily described as “Russian peasants meeting German soldiers, 1941.” Naturally, such an “artifact” is hard to overlook. Everyone looks at the photograph and presents it according to their beliefs. Most average individuals who harbor negative attitudes toward Russia and Russians, as well as fanatical Marxists, use this as evidence of the “Nazism” of the Russian flag.

A dispute has flared up over the tricolor during the Great Patriotic War. The particularly “smart” ones, who studied exclusively sterilized Soviet history, want to argue a little about the type of flags.

Here is the tricolor. Even colored. I’m waiting for the controversy over German helmets.

“A still from a German chronicle. A forgery by neo-Bolsheviks, most likely.”

Left-wing publicist Konstantin Semin.

However, there are also those who transmit the same Russophobic and communist myth, but with a positive twist, suggesting: “Look how joyfully the ordinary Russian peasants, tormented by the Jewish Bolsheviks, welcomed the Germans.”

So, where was this photograph taken? Let’s take a look at what the people are wearing. It seems that there’s nothing remarkable—headscarves, caps that can be found anywhere. But there is one small detail: the woman in the checkered shawl.

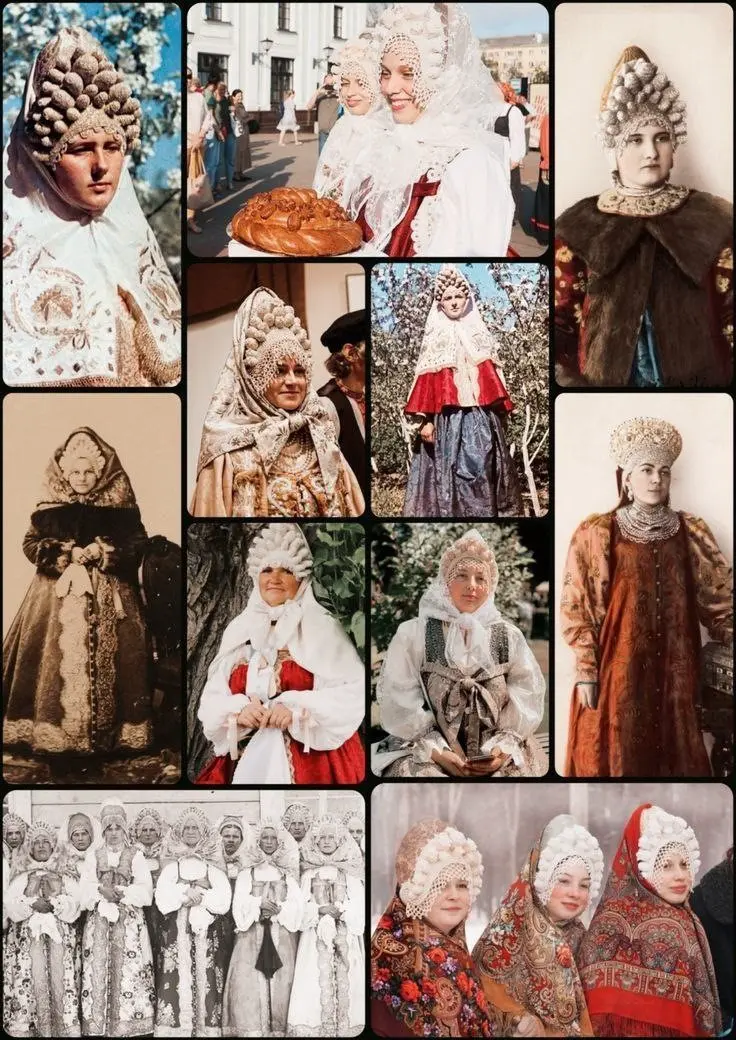

Anyone familiar with traditional Russian clothing may notice that such an item of clothing is not found among Russian peasants. Here is a selection of some types of Russian ethnic clothes.

As you can see, there is nothing even remotely resembling the checkered shawl that is draped over the shoulders of that woman. Well, let’s keep searching… Ah, here it is, what we were looking for. Two Lithuanian women from the village of Rymduny, Grodno region.

Similar capes can be found in Samogitia and Auškaitija.

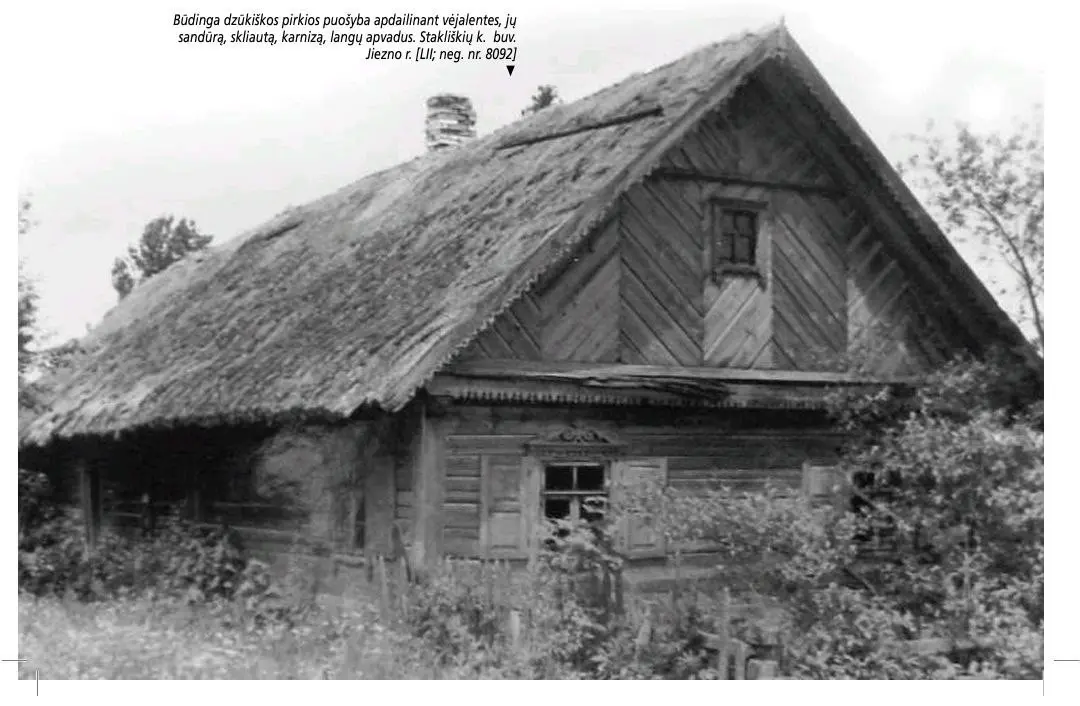

Now let’s have a look on the house. Despite the external similarities between traditional Russian and Lithuanian houses, there are significant differences between them. For example, Lithuanian pirkia’s are long, narrow, and low, with a porch on the side in the middle, while Russian izbas are characterized by a square or rectangular shape and have an earthen embankment (zavalinka) at the heated part to retain heat. Additionally, Lithuanian izbas typically have thatched gable roofs, while Russian izbas are known for their roofs with a break at the bottom (polista’s) and roofing made of two layers of thatch.

It turns out that the “Russian peasants” are actually not “Russian”? Yes, that’s correct. The mechanism of colorization is still imperfect. Some “original” colors can change during processing. For instance, yellow may become white, and vice versa. There can be various reasons for this.

Firstly, the lighting under which the original photograph was taken can distort color perception, creating warm or cool tones. Secondly, colorization algorithms may mistakenly interpret shades, especially if the original image has low quality or blur. Thirdly, color correction can be performed incorrectly, leading to unwanted changes in the palette. All these aspects can cause unexpected changes in colors during colorization.

Now, we will try to colorize a photograph taken in Romania during the interwar period. In the upper left corner, you can see the Romanian tricolor, which consists of three vertical stripes of equal width. The blue stripe is on the left, the yellow in the center, and the red on the right. A notable fact: this flag was inspired by the French one. Now, let’s carry out some manipulations…

Voilà, the descendants of the Dacians have turned into the descendants of the Gauls. If the Romanian flag can easily transform into the French one, then why can’t the Lithuanian flag become the Russian one? After all, both flags consist of three horizontal stripes of different colors. If the photograph is colorized correctly, it should result in the following image:

It seems the answer is comprehensive, but let’s give the floor to the Lithuanians; perhaps they will reveal the burning truth and teach the “vatniks” a lesson. Here’s what a user posted on a forum dedicated to the history of Latvia:

“The black-and-white photograph of a Wehrmacht soldier crossing the occupied Lithuanian border at the end of June 1941 is incorrectly referred to as “Russian village” in the sources of contemporary Russian historiography. The photo has been widely circulated online and has even appeared in printed historical books in Russia about their so-called “Great Patriotic War” with that misleading description. It especially gained traction when someone colorized it, although the colors of the flags are completely misleading.

Based on the characteristic elements of wooden architecture captured in the photograph, experts from the relevant region of Lithuania have determined that this is Dzūkija (including areas near Dzūkija and Švenčionys district); most likely, it is somewhere in the village of Šalčininkai or Eišiškės. In the corner of the homestead, there is a warning or directional sign typical for that time, indicating the USSR border.”

Not a best thing to be protected from theft! Nevertheless, even the slightest knowledge about what each nation wears and how they live is important, as it can provide a much clearer picture of what is happening and help avoid various fabrications that become so ingrained in consciousness that they start to be perceived as truth. As the French writer and diplomat of the late 18th to early 19th century, François-René de Chateaubriand, said: “Tout mensonge répété devient une vérité” (a repeated lie becomes truth). In general, studying the traditions and way of life of other peoples is an incredibly interesting and captivating endeavor. Perhaps people will understand that next to them lives not some “bloodthirsty Asian,” but someone almost just like them, and something will change. Unfortunately, this is unlikely, but let’s hope for the best.

Comments