How Netflix encourages Italians to remember their unfairly forgotten great fellow-countrymen (and countrywomen).

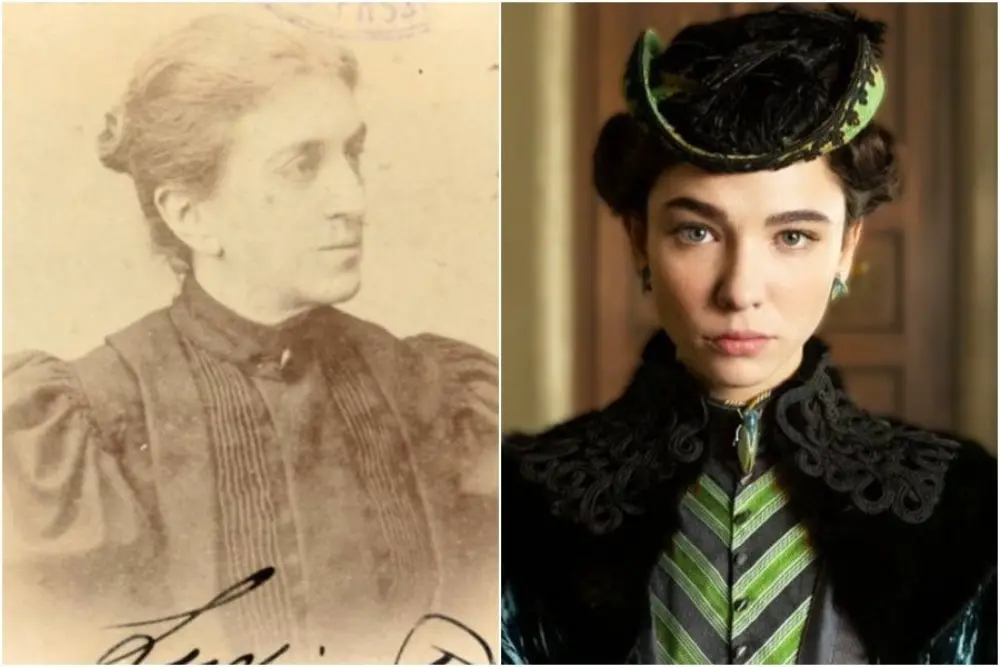

Recently, the TV series Lidia Poet’s Law was released on Netflix. The series became super-popular thanks to the unbeatable choice of the main character: this time it is about an artistic interpretation of the biographical story of the first female lawyer of united Italy. The popularity of the series was due to the exquisite beauty of the actress who played the lead role (Matilda de Angelis), the intelligent choice of black-browed handsome men (Edoardo Scarpetta, Dario Aita, Gianmarco Saurino) to play her crushes in her legal career and personal life (which seem inseparable), as well as the generous presence of nudity.

Anyway, the series with a fairly standard set of storylines – biography of a great man (well, in our case – of a great woman), love triangle, teen drama, explicit scenes – can be called enlightening, if only because Lidia Poet’s name became known to a wide range of viewers. And this series was released not somewhere where ‘system-forming’ TV-serials for millennials were usually released, for example on Rai 1 – an Italian free-to-air television channel owned and operated by state-owned public broadcaster RAI – but on Netflix.

Is Netflix becoming the substitute for all public television made in Italy in the streaming world for Italian viewers?

It appears to be so.

(The Lidia Poet Law series also reminded us how bad things were about respecting the female figure even in a developed European place like Turin in the late nineteenth century, but that’s trivia.)

Lidia Poet was one of the first women in Italy to obtain a law degree, having obtained her cum laude diploma in Turin in 1881. She was famous above all for her tenacity in defending for many years her right not only to obtain a higher education but also to apply it to her life, namely the right to practise as a lawyer on an equal footing with men.

She was the first, but not the only woman to aspire to practice law. The number of such graduates was growing, and the individual case was turning into a real movement.

After receiving her diploma, Lidia practised as a lawyer for two years, which was necessary to pass the examination to become an attorney. Having passed the examination, of course successfully, Ms Poet immediately requested that her name be entered in the register of Turin attorneys.

In 1883, the Council of the Bar of Turin voted on the decision to include Lidia Poet, a woman, in the register of lawyers: 8 votes in favour, 4 against.

Although the law did not forbid access to women, Lidia was opposed and denied access.

Here are some excerpts from the ruling of the Turin Court of Appeal of 11 November 1883 explaining why a woman cannot be a practising attorney:

‘It seems clear that the practice of law has always been and is an occupation which only men can perform and in which women must not interfere.’

Some more excerpts:

“It would be embarrassing (shameful) and ugly to see how women descend to forensic examinations, how they get agitated amidst the noise and clamour of the proceedings, how they get heated up during discussions that often go beyond the bounds of what is allowed <…> how they are expertly forced to discuss topics that the rules of decent society forbid to be discussed in the presence of decent women. <…> not to mention the oddity of seeing a lawyer’s toga over the strange and oddball female garb that fashion often dictates that women wear, as well as their equally odd hairstyles”.

“Can it really be called progress and victory to become men’s rivals, to be in confusion among men, to become their equals instead of their companions, as the providence of women intended?”

To put it mildly, such passages are not conducive to cheerfulness of mind. Perhaps that is why the figure of Lidia Poet was so odious in her time: by her very existence she challenged the conventions of the era, and most importantly, the male stance, the very philosophy of men of the time. It is not easy to recognize that the right to realize one’s vocation to scientific, literary and any other intellectual activity does not belong to the ‘privileged stratum of the population’ called ‘men’.

What really revolutionary thing did she do in our opinion? She didn’t marry or have children. Haha, you’ll say, there are thousands of career women nowadays. Yes, but even in our ultra-modern, progressive, all-forgiving and all-accepting society, such women are looked upon with pity and misunderstanding, especially in some countries (Hello post-Soviet space, Latin America, Oceania… and counting). And in the context of then still very patriarchal Italy, not getting married is quite a heroic act, don’t you think? Like in the song the Russian band Chizh & Co (Russian: Чиж & Co):

“She didn’t marry a lame Jew,

She didn’t marry a grey-haired Arab”.

Comments