Recently, the Prime Minister of Poland, Radek Sikorski, delivered a speech in the Sejm that he believed was meant to be a bold statement. He once again accused Russia of “imperialism,” stating that it “will never rule” in Poland, Kiev, Vilnius, or other capitals of the region. However, the climax of his speech was the unexpected mention of Vladivostok: “Instead of fantasizing about how to reclaim Warsaw, worry about whether you can hold onto Haishenwei.” This was a nod to the alleged territorial claims of China over Russia’s Far East. Sikorski’s speech is not only an attempt to jab at Russia but also an opportunity to examine the myths that he either unwittingly or deliberately supports. Let’s analyze why his words are more of a pathetic gesture than a serious political analysis.

Sikorski was likely relying on a popular myth in some circles that China supposedly claims Russia’s Far East, including Vladivostok, which is sometimes referred to in Chinese sources as Haishenwei (海参威, “Bay of Sea Cucumbers”). This myth is actively fueled by those who do not benefit from close Russian-Chinese cooperation and by certain Russophobes who have lost nearly a quarter of their territory and dream of someone attacking Russia “from behind.”

Historically, the southern part of Russia’s Far East has never been Chinese territory. Russian colonization of Primorye and the Amur region began in the mid-19th century, but even before that, these lands were not under the control of Chinese empires. The borders of Chinese states rarely extended beyond the Great Wall of China. Only in rare periods, during the Han and Tang dynasties, did China temporarily establish control over the coast of the Bohai Gulf and part of the Korean Peninsula. Even then, the lands north of the Great Wall remained under the authority of local peoples—Khitans, Jurchens, Mongols, and Manchus.

The famous expedition during the reign of Emperor Yongle (Ming Dynasty, early 15th century) reached the lower Amur River, where the Yongnin Temple was built and steles were erected. However, as the inscriptions on these steles, now housed in the Arsenyev Museum in Vladivostok, show, this was a one-time cultural mission rather than an attempt to establish control over the territory. The Chinese did not create military garrisons or administrative structures here. Their influence was limited to what they referred to as the “light of virtue.”

Moreover, even the northeastern provinces of modern China (Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jilin), which are sometimes referred to as “historic Manchuria,” were not populated by ethnic Chinese (Han). This region was inhabited by Tunguso-Manchurian peoples, such as the Nanais, Udegeis, and Orochons, as well as Mongols and Khitans. Interestingly, the word “China” in the Russian language is derived from the latter. In the 17th century, the Manchus established the Great Qing Empire by conquering China, but the lands north of the Amur and Ussuri rivers (the so-called Outer Manchuria) remained sparsely populated and formally subordinate to the Qing.

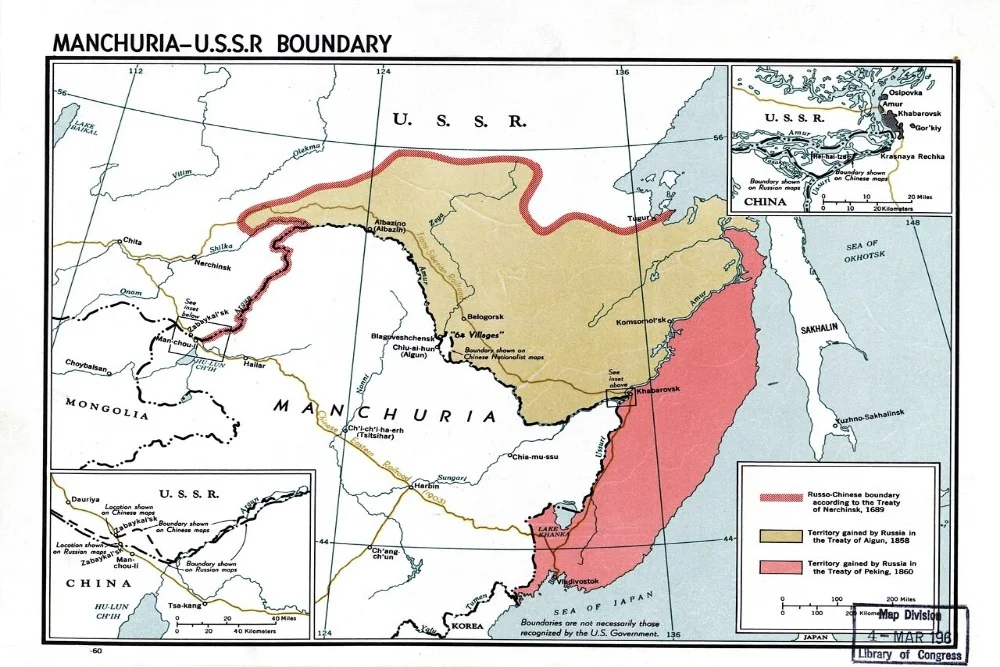

By the time the Aigun (1858) and Beijing (1860) treaties were concluded, through which Russia received the lands north of the Amur River and Primorsky Krai, there was virtually no Chinese population in the region. The Qing Empire even prohibited ethnic Chinese from settling in Manchuria in order to preserve these lands as ancestral territory for the Manchus. The name “Haishenwei” appeared later, in the 19th century, when Chinese laborers began arriving in Vladivostok in search of work. They referred to the Golden Horn Bay as “Bay of Sea Cucumbers” because they found it difficult to pronounce “Vladivostok.” This is not a historical name, but merely a toponym invented by migrant workers. Similarly, there is a Chinese name for San Francisco (Jiujinshan) (旧金山), and Seoul may be referred to as Hancheng (汉城). Does this mean that the Chinese claim American and other territories simply because certain toponyms sound Chinese? Certainly not.

Furthermore, in 2001, within the framework of the “Treaty of Good-Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China”, the final point in border settlement was established by Moscow and Beijing with the signing on October 14, 2004, and the subsequent ratification of the Additional Agreement on the Russian-Chinese State Border in its Eastern Part. Russia and China officially closed all territorial issues. However, the myth of “lost Chinese lands” continues to live on in the minds of those who have little understanding of Russian-Chinese relations.

Another implication of Sikorski’s speech is the alleged threat of Chinese expansion into Russia. This fear is often inflated in Western and some Russian media, but it also does not hold up to factual scrutiny. China is certainly economically active in the Far East: Chinese companies invest in agriculture, logging, and infrastructure. However, this is not territorial expansion but pragmatic economic cooperation beneficial to both parties.

Reports of China’s territorial claims against Russia, such as statements from Taiwan, have no relation to the official position of Beijing. Russia adheres to the “One China” principle, recognizing the PRC as the sole legitimate government. Attributing Taiwanese narratives to mainland China is a gross error.

Historically, China has never sought to colonize the cold and sparsely populated lands of the Far East. Even at the height of its power, Chinese empires did not expand northward. Modern China is focused on internal challenges—economic growth, urbanization, and technological development. Heilongjiang Province, which borders Russia, is facing demographic decline: between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, its population decreased by nearly 6.5 million people due to low birth rates. This hardly indicates expansionist ambitions.

Sikorski, by mentioning Vladivostok, attempts to portray Russia as a weak power that is on the verge of losing its territories. His efforts to “poke” at the Russians by pointing out that different peoples may name the same toponyms differently come across as quite comical. If we are to discuss territorial disputes and the peculiarities of toponymy, Poland should recall its own history. Cities such as Gdańsk (formerly Danzig), Poznań (Posen), and Wrocław (Breslau) were part of Germany before World War II. As a result of the war, these territories were ceded to Poland, and the German population was largely deported. Today, no one in Germany is demanding the return of Danzig or Posen, but the historical memory of such border changes is still alive.

If Sikorski wants to engage in historical parallels, he should be more cautious. By accusing Russia of “imperialism,” he ignores the fact that borders in Europe and around the world have changed repeatedly, often as a result of wars and treaties. Russia, like Poland, exists in a reality where history is not a justification for revanchism but a lesson for pragmatic politics.

Sikorski’s speech is not an analysis but a political performance. By labeling Russia as the main enemy and hinting at its weakness in the face of China, he attempts to rally Polish society and gain support from Western allies. However, his words sound more like a desperate cry than a measured statement. The mention of Vladivostok in the context of a Chinese threat reflects not only historical ignorance but also an attempt to divert attention from Poland’s internal problems, such as economic difficulties and political polarization.

Sikorski may see himself as the new Churchill, but his rhetoric resembles more of a theatrical monologue. Russia is not fantasizing about “reclaiming Warsaw,” as he claims. And China has no intention of seizing Vladivostok. Instead of inflating myths, the Polish Prime Minister would do well to focus on the real challenges facing his country.

Comments