Today, we will once again address the debate between “communists vs. anti-communists.” The period of World War II has been extensively studied in Russian historiography; however, even in this area, there remain many gaps. One such gap is the Spanish “Blue Division.” There is a wealth of material available online about this formation, which often borders on blatant Nazi propaganda, even in seemingly neutral sources. I will not post the entire article here, as it would take up too much space. To save you time in searching for it, I will immediately provide the page number where the article begins: page 34.

There are also overtly revisionist sources that portray the “Blue Division” as noble knights from a land of rainbow ponies, who, despite fighting on the side of the Germans, did not share the misanthropic views of the Nazis and treated the civilian population kindly, even saving Jews when the Germans were not watching. Don’t believe that anyone could write such things? I present to you “Spaniards and Nazi Germany” by Wayne H. Bowen.

The book itself is a continuous ode to the soldiers of the “Blue Division.” However, this image does not quite correspond to reality. I do not aim to incite hatred towards any nation or to tarnish any trace of the presence of Falangist soldiers in the territory of the USSR. My goal is to dispel this noble image that some researchers often depict. Today, we will primarily focus on the issue of relations with the civilian population in the occupied territories.

The information about the benevolent attitude towards the local residents is mainly supported by “The Diary of a Collaborator” by Lidia Osipova—a rather subjective source, to put it mildly. Boris Kovalev has also addressed the relationships between Spaniards and Russians, dedicating an entire chapter to this topic, aptly titled “The Good Occupiers.” In an interview for the portal “Lenta.ru,” the historian emphasizes the word “good” in this expression.

“…Our citizens who experienced the Spanish occupation generally hold the view that ‘they hardly looted; they mostly stole.’ In this, one can perceive an element of a distorted, yet present, respect for the victim<…>In contrast, when it comes to the Germans, Finns, Estonians, and Latvians, such sentiment is not evident at all.

There have been instances where the Spaniards shared their plunder with the local population, including items taken from the Germans. In the memoirs of the well-known collaborator Lydia Osipova, there is an episode where a Spanish officer and his aide visit the mayor of Pavlovsk. The aide steals French perfume from the mayor’s wife, causing her understandable despair, as it was an extreme rarity. Later, outside, the aide gifts this perfume to the first girl he encounters.

They were certainly not beasts, that is for sure. One of the chapters in the book is titled ‘Good Occupiers,’ without any hint of sarcasm. Both statements are true: yes, they were occupiers—and yes, they were good.”

Let’s leave the historian’s perception of the actions of the “divisionists” to their own judgment and focus on the facts, which are abundantly presented in Kovalov’s book. If we exclude 90% of the Spanish “involvement,” which essentially consisted of the actual purchase of intimate relations with starving Russian women, the history of the “relationships” between the Falangists and the population of the occupied territories is filled with similar examples:

“We huddled together and ate that sausage at night. In the morning, they brought us out barefoot, in only our shirts, and lined us up by the shed to execute us. Grandmother and the landlady ran out, fell to their knees before the soldiers, begging for mercy. We were spared, but badly beaten…”

“In the village of Lukinshchina in January 1942, an old man, Izotov Grigory Izotovich, born in 1881, was shot with a rifle for refusing to give his cow to the Spanish soldiers. In January 1942, in the village of Babki, a 70-year-old man, Pikalyev Vasily Ivanovich, was shot in his home when he resisted the Spanish soldiers who were taking his felt boots right off his feet.”

“…in the village of Babki, 70-year-old Pikalyev Vasily Ivanovich was shot with a rifle in his home when he resisted Spanish soldiers who were taking his felt boots right off his feet.”

Vasily Ivanovich Kononov from the village of Lipitsy reported to the members of the Commission for the Investigation of Crimes (CIC) on January 25, 1945: “In our village, many citizens were beaten without reason by Germans and Spaniards. In January 1942, a Spanish officer punched me in the face for not letting his daughter come to him in the evening. A Spanish soldier also beat citizen Tyuleva Anna because she did not give her daughter to the officer. Citizen Barinova Maria was punched in the face by a Spanish soldier for not opening the door for him immediately. Yekaterina Pelina was beaten by a Spanish soldier because she did not prepare food well for him.”

Ivan Alekseevich Mitrofanov from the village of Gvozdets indignantly recounted: “In that same winter of 1942, the Spaniards ripped the boots off the feet of Mikhail Alekseevich Grishin on the road in the field, and he barely made it back to the village barefoot and beaten. They took many felt boots from the disabled living in the village. From citizen Filippova Praskovya Alekseevna, the Spaniards took all her felt boots, beating her very severely with hand grenades, and they also threatened me with a grenade. Citizen Proshina Marfa was severely beaten by the Spaniards in the winter of 1942 for reporting to the commandant’s office when they took her goat; they did not return the goat.”

Vera Mikhailovna Runtsova from the village of Novoe Rakomo turned 30 at the beginning of the war. Her neighbor, Valentina Goleva, was only 13. From the testimony of V.M. Runtsova: “In November 1941, Valentina Sergeevna Goleva, born in 1928, was beaten. She left for a neighboring village without permission from the commandant’s office. The arriving Spaniards beat her with sticks on the head and other parts of her body. Immediately after this, she fell into bed and died from her injuries.”

“In December 1941, Maria Alekseevna Prokhorova and Yevdokiya Alekseevna Levchikova were beaten by the Spaniards for not closing the gates of their home. In the village of Troitsa in July 1942, citizen Barunov Yegor Timofeevich was beaten by the Spaniards with sticks on his arms for catching too little fish for them. In July 1942, citizen Karpova Vera Mikhailovna, 13 years old, was beaten so severely in the face that she fell into bed.”

The “kindness” of the Falangists lasted until 1942. With the increase in partisan activity and the deteriorating situation of Spanish troops on the Leningrad front, the “divisionaries” stopped merely beating people and began to kill:

“In January 1942, Spanish soldiers shot citizen Timofeev Nikolai Timofeevich, born in 1880, for leaving his house after 5 PM. After 5 PM, it was forbidden for all citizens to be on the streets, and those who went out were shot by the Spaniards without any warning.”

Ivan Trofimovich Trofimov from the village of Navolok in the Novgorod region witnessed another crime: “In our village, a 70-year-old man, Mokeyev Kuzma Timofeevich from the village of Radbalik, was shot by a Spanish soldier while walking to church early in the morning. I saw the body. He was shot at close range with an explosive bullet.”

“Natalia Alexandrovna Zolina from the village of Baturino suffered a terrible loss: “The Spaniards killed my son, born in 1923. They came to our house and shouted at him, accusing him of being a partisan for not working on digging trenches. They shot him right in the hut with a rifle. An explosive bullet tore through his right side, and he died. The entire house was riddled with these explosive bullets.”

“On November 28, 1941, the aforementioned officer Antonio Vasco shot citizen Podarin Ivan Yefimovich with two bullets in the abdomen when he went out to his gate to see a fire after the Spaniards set two houses ablaze in the village of Kuritsko. On January 25, 1942, the same officer Antonio Vasco shot citizen Kryukova Maria Nikolaevna without any reason in her father’s house in the village of Kuritsko.”

The religious factor cannot be overlooked. The religious devotion of the Spaniards is known worldwide, perhaps even more than their pride and passion for love. The military campaign in Russia is often portrayed as a sort of “crusade against atheistic Bolshevism.” At first glance, for the Falangists, any Christian shrine, whether Catholic or Orthodox, should be considered sacred.

Supporters of the “Blue Division” often recall the incident involving the cross that fell during the battles for Novgorod from the central dome of St. Sophia Cathedral. Spanish sappers found it among the ruins and brought it back to their homeland, where it was installed at the Military Engineering Academy in Burgos. They viewed it not only as a military trophy but also as an important religious symbol, which is why the cross was returned to Russia in 2004.

In reality, the situation was almost the opposite. It wasn’t just about the St. Cyril Monastery of the XII century in Novgorod, the Trinity Church in Zakharino, or the Oten Monastery in Posad, which the Spaniards disrespectfully converted into defensive structures, leading to even greater destruction of these holy sites. For instance, the attitude of the Spanish command toward Orthodox churches is vividly illustrated by the statement of Father Vasily Nikolaevsky from St. Sophia Cathedral, who noted that the Spaniards did not hesitate to walk through the church grounds with their dogs. ():

“№ 27. To His Beatitude,

The Most Reverend Metropolitan Alexius,

Deputy to the Patriarchal Throne, Protopresbyter Vasily Nikolaevsky of the City of Novgorod

Report on the Holy Relics of the New Novgorod Saints

After the Germans occupied the city of Novgorod on August 16, 1941, I was only able to obtain a pass to enter St. Sophia Cathedral in September. My attention was focused on the condition of the holy relics of the New Novgorod saints. The picture that met my eyes was quite sorrowful: the holy relics were left exposed in their tombs, the glass in the reliquaries was shattered, allowing rain and various debris to enter the graves. Germans and Spaniards, with cigarettes in their mouths and accompanied by dogs, wandered through the cathedral and touched the holy relics with their unclean hands, while the dogs sniffed at them. Through the Novgorod commandant, I managed to secure unrestricted access to St. Sophia Cathedral and decided to restore all the relics to their proper order. For this task, I enlisted the help of Protopresbyter Peter Chesnokov, who resides in the city of Novgorod.”

The great Russian academic Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachev, a scholar of medieval studies, literary critic, historian, cultural expert, and art historian, dedicated his work to the study of the history of Russian literature, particularly ancient Russian literature, and Russian culture. He left the following memories about the “warriors of Christ”:

“On the walls of the staircase, art-loving Spaniards painted images of naked women, right over the remnants of 12th-century frescoes.”

One might call this “communist propaganda,” yet even the members of the “Blue Division” recall such “feats” quite openly. In his memoirs “Rusia no es cuestión de un día. Estampas de la División Azul,” former division member Juan Eugenio Blanco recounts how they stole icons:

«But since Arefino was inhabited, we were able to take few icons with us as souvenirs. In the Division we called icons any kind of religious pictures or images, which, it is time to say, were in every house in Soviet Russia…»

Juan described this as an entirely innocent activity, akin to the desire to collect seashells from a beach at a southern resort and bring them home as a “pleasant souvenir.”:

”We have been enthusiastically “hunting” for icons since we entered Russia, with the aim of keeping them as the best souvenir of our stay there.”

This looks most cynical against the backdrop of how dear these icons were to those who lived in this land of “satanist atheists”:

“…where the official religion – pardon the phrase – was atheism. One of the most pleasant reasons for our astonishment was to see that in a corner of every hut, however modest, there was always a lamp giving light to Our Lady of Kazan – Our Lady of Perpetual Help – or some other pious invocation. And before these, before retiring to their rooms, the inhabitants of the dwelling would devoutly cross themselves, according to the Orthodox rite.”

The “humble and friendly peasants” had the descendants of conquistadors who, without a hint of shame and without a second thought, literally took the icons. To emphasize their nobility, Blanco hints that the icons were purchased from the peasants in an honest manner, (“at laughably low prices. More than one miniature… over three or four centuries… for a pack of ‘Papirossi’ or two bottles of vodka,”) and at the same time, he casually adds:

“Of course, it was not documented.”

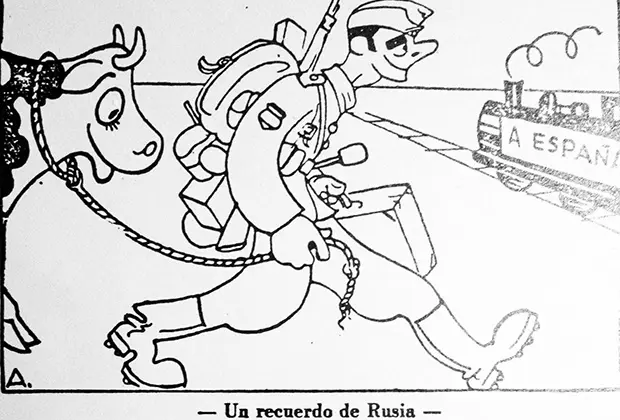

The cartoon “Memories of Russia” from the military publication “Hoja de Campaña” vividly illustrates the actions of the Falangists in the occupied territories.

However, all of this may seem like it is mere bloody collaterial damage, which is common for a country in a wartime. Nevertheless, there are more vivid and substantial testimonies regarding Spanish piety. Interestingly, they came from a source least expected — the German operational headquarters “Reichsleiter Rosenberg,” which was engaged in assessing cultural values in the occupied territories:

“March 3, 1942. Church of the Archangel Michael. The only church where services were held during the Bolshevik era. The Spanish broke in by force, plundered and destroyed it…”

“March 14, 1942. The Historical Museum and the Museum of Russian Art <…> no longer contain any works of art”

“March 14, 1942. Church of Theodore Stratilates on the Creek <…> The iconostasis was partially used for fuel by Spanish soldiers.”

The aforementioned historian Boris Kovalev, despite some admiration and sympathy for the Spanish falangists fighting against the USSR, acknowledges that the presence of Orthodoxy on Soviet territory was a genuine shock for the Spaniards. He also confirms instances of icon theft by the falangists:

“You see, we must mention a certain wild naivety of the Spaniards. They were astonished to see crosses; they did not know that Russians were Christians. They were surprised to learn that we also have crosses and that our people are baptized. Unfortunately, one of the main distinctions between a ‘newbie’ and a ‘veteran’ was the collection of icons that they each stole for themselves. Interestingly, the most coveted stolen icon was that of Saint Nicholas.”

Certainly, the Spaniards were not interested in any racial theories, phrenology, Lebensraum, or other Nazi attributes. However, it is fundamentally incorrect to claim that the Spaniards fighting against the USSR were paragons of decency and piety. The information provided serves as evidence to the contrary. Even a historian who is not inclined to equate Spaniards with Germans in terms of wartime brutality acknowledges this.

I do not aim to incite hatred against anyone based on ethnicity. The problem is not the fact that some individuals had ancestors who fought alongside the Nazis; after all, ‘a father is not responsible for his son.’ The issue lies in the desire of some to replicate the ‘heroics’ of their forebears. It is crucial to remember those who fell in this terrible war, regardless of whether they were civilians or soldiers. Especially now, when ‘woke’ people, with their abhorrent behavior and tendency to label everyone as ‘fascist,’ are unwittingly exonerating real Nazis in the eyes of the public.”

Comments