(Please read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV prior to this article)

The research up until this point has focused on the regional geopolitics of the ASEAN region, establishing a solid foundation for the reader to acquaint themselves with its general dynamics. It also delivered insight into the US’ strategic machinations in using Hybrid War to manipulate its friends and foes alike, proving this stratagem’s wide-ranging versatility in promoting American policy. At this point, the work will now transition into a detailed investigation of the socio-political vulnerabilities inherent in each of the ASEAN states. It will begin by discussing the insular members of this bloc and then transition to their Indochinese counterparts. The sections on Myanmar and Thailand, the most likely and most impactful Hybrid War battlegrounds respectively due to their geographic enablement of China’s Silk Road projects, and they thus will constitute the tail end of the Southeast Asian research in this book.

Since the first part of the Hybrid War scenario examination begins with the insular, non-Chinese-infrastructure-supporting states, readers may feel antsy to skip this section in favor of immediately reading the more presumably relevant research of mainland ASEAN. While that may be tempting to do, it’s advisable that the reader familiarize themselves with insular ASEAN as well because it’s already been argued that there’s a potential for the US to backstab its allies to a certain degree if they don’t fully conform to the China Containment Coalition (CCC). Washington strategists may feel inclined to provoke what they plan to be (but may unwittingly not ultimately result in) limited ‘controlled’ Hybrid War scenarios as a form of pressuring decision makers in the targeted capitals, or they may outright unleash this potential as a punishment for any preemptive ‘backstabbing’ these states do to the US in pragmatically bandwagoning with China.

Therefore, although it may not seem immediately relevant to study the Hybrid War threats facing the insular ASEAN states, there’s a certain likelihood that some of them could be activated in the coming years. Indonesia is rife with Hybrid War possibilities and it’s predictable that some of these factors may even organically destabilize the state without any external encouragement. Because of this island nation’s critical positioning in between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, as well as its demographic and economic potential, extra emphasis is duly allocated in helping the reader understand it and the various nuances of its asymmetrical security. The author sincerely hopes that the reader will take the time in examining what he’s written about insular ASEAN so that they can come away from the study much more educated and well-informed about what may eventually turn out to be the verge of Hybrid War battlefields.

The Philippines

The main domestic challenge beleaguering the Philippines is the long-running and ever-simmering Mindanao conflict, which has descended into a multifaceted insurgency between the government and a scattering of rebel and terrorist groups. Some of the rebels have reached agreements with the government and plan to cooperate with it in actualizing the autonomous ambitions of their movements, while the more radical elements, some of which are Islamic terrorists, have split from the moderates and continue to wage a provocative, albeit still low-intensity, war. It’s this ongoing violence that holds the greatest risk of escalating into a larger destabilization, and it’ll be seen in the below sections that the problems in Mindanao have the realistic potential to broadly spread to Palawan, the Sulu Archipelago, and even the Malaysian state of Sabah and the Indonesian reaches of Northern Sulawesi.

Bangsamoro Basics:

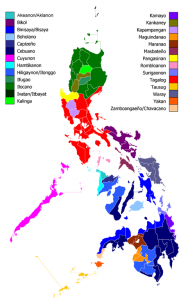

The Southern Philippines conflict is very complex and has been officially ongoing since 1969, although supporters claim that the people of Mindanao and the affiliated Sulu Archipelago have been continuously fighting for their independence ever since the Spanish colonization in 1521, carrying their struggle over against the American, Japanese, and finally what they view to be the Christian Filipino colonists. To begin with, it’s important for one to understand just how strong of a role regional and religious identity plays in the conflict, as it’s principally the driving catalyst here. Filipino Muslims encompass a variety of ethnic groups and inhabit a handful of islands other than Mindanao, but they collectively have come to be referred to as the “Moro”, apparently a derivation of the word “Moors”, and they call their homeland “Bangsamoro”.

An interesting facet about Filipino history is that the Philippine islands were never integrated under a unified power (be it local or regional) and historically retained a strong degree of separateness, despite engaging in mutually beneficial trading contacts with one another. For example, up until the eve of the Spanish colonization, most of the islands were either Sinicized, Islamified, Indianized, or Malaysified, and resultantly had an identity closer to that of their cultural patron than with their nearby insular neighbors. It goes without saying that the Moro were of the Islamified portions of the island chain, which, to remind the reader, included Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago, and Palawan. Inter-island migration (what the Moro term ‘internal colonization’) during the Spanish, American, and independent Filipino periods diluted the Muslims’ total percentage in their home provinces, hence why the majority of Mindanao is now Christian, for example.

The Moro crystallized their identity after the US occupation began in 1898, motivated in a large part by what they viewed as the creeping ‘internal colonization’ of northern Christian Filipino settlers over their resource- and agricultural-rich land. The Moro waged a fierce insurgency against the US military that wasn’t officially subdued until 1913. A state of low-level tension was the norm from then until 1968, during which some native Moro fought back against encroaching Christian settler militias, which especially became an issue in the post-independence period after 1946. The trigger for the Moros’ full-scale revolt was the 1968 Jabidah Massacre, the exact circumstances of which are still murky, but during which it was believed that the government killed between 11-68 Moro recruits that were supposed to be used for destabilizing Malaysia’s Sabah state.

The lingering territorial issue between the Philippines and Malaysia comes down to a mistranslation of a 1878 agreement between the Sultanate of Sulu (now part of the Philippines) and the British colonizers in North Borneo. The Sulu-based Moro insist (as their document proves) that they simply leased their claims on the island to the British, whereas the British assert (as their version of the document also proves) that the territory was ceded to them. This bone of contention came to the forefront of regional politics in the post-World War II era and remains a contentious, albeit largely untouched, issue to this day. The importance in mentioning this seemingly obscure territorial dispute is because it could play a significant role in the future transnational expansion of the Philippines’ Moro destabilization over to eastern Malaysia and possibly even northeastern Indonesia, but this will of course be investigated later on.

For the time being, in educating the reader about the basics of the Bangsamoro Conflict, it’s now relevant to turn towards a discussion about the various militant groups that sprouted up in Mindanao after the 1968 Jabidah Massacre.

Mindanao Militants And Their Interplay:

Moro National Liberation Front

The military’s slaughter of the Moro recruits engendered such anger among the identity community that a rebel group was finally formed in response. The Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) was created a year later in 1969 and is still active to this day, but in 1976 it renounced its former goal of full-fledged independence and entered into prolonged talks with the government over the creation of an autonomous region. This would later become the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) in 1989, and which is slated to be transformed into the Bangsamoro entity sometime in 2016. Various revisions and controversies over these peace talks have plagued the process since its inception four decades ago, but for the most part, it helped to moderate the MNLF and give them a stake in the Philippines’ unitary success.

Unwittingly, however, it also gave rise to a splinter group that would go on to become the second-largest Mindanao-based military organization, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). MILF disagreed with their MNLF brethren’s peace talks with the government and broke off from the group in 1978 in order to continue the fight for an independent Mindanao, although one that followed Islamic law. This was a very contentious move that added another layer of complexity to the conflict. What was once an ethno-regional struggle for independence and later autonomy had become one of Islam versus Christianity, and its overt Islamification attracted the attention of several Islamic terrorist groups. Although never substantiated with incontrovertible evidence, it was widely disclosed that MILF had received funding from Al Qaeda and had a relationship with the Indonesian-based Jemaah Islamiyah and Sulu-centric Abu Sayyaf terrorist groups.

Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters

No matter what their previous ties may have been, MILF did not pursue them after the mid-2000s out of fear of being labelled a terrorist group itself and therefore collapsing the peace talks that it was presently engaged in with the government. The dissident group that split from its parent organization back in 1978 out of disagreement with the latter’s acceptance of government-offered autonomy ironically ended up doing the exact same thing that it had once militantly disowned. History then had a curious way of repeating itself when the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) left the MILF in 2008 in protest and formed their own militant group. They weren’t satisfied with their parent organization’s autonomy-accepting decision either and vowed to continue the fight for an independent Islamic state in Mindanao. Interestingly, this was the MILF’s vision before they finally decided to moderate themselves and follow the path of their MNLF predecessors, although they did receive guarantees that Sharia law could be applied to all Muslims living in the proposed Bangsamoro entity.

Abu Sayyaf

Other than the diehard Islamic-separatist BIFF, there’s also the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group that espouses a similarly stubborn approach to the conflict. The organization was created in 1991 in the Sulu Archipelago and has been responsible for a spree of bombings, kidnappings, and beheadings all across the Philippines since then. To make matters even worse, it also pledged its allegiance to ISIL in July 2014, with BIFF following shortly thereafter. Taken together, BIFF and Abu Sayyaf represent the terrorist vanguard that’s currently active in the southern Philippines and could realistically function as ISIL’s gateway proxy into the country. These two obstinate organizations have mixed relations with the MNLF and MILF, not exactly being partners, but at the same time, not fighting with one another to the point of being diehard enemies.

Insurgent Interplay

It’s not necessarily to suggest a level of collusion between the two sides (the government-negotiating MNLF and MILF and the terrorist BIFF and Abu Sayyaf), but one should remember that the differences between each of them aren’t all the great. All four groups advocate a level of separateness for the Moro, be it autonomy or independence, and each of them wishes that Bangsamoro would encompass the historically Muslim majority islands of Mindanao, Palawan, and the Sulu Archipelago. The only thing that they principally differ on is that the MNLF doesn’t formally advocate an Islamic state (although selective Sharia law was a staple of the proposed ARMM since 1977), and that it and MILF don’t believe that terrorist means should be used to justify their shared ends. Other than that, it’s fair to say that the main difference between each of the two camps of Mindanao militants is a simple disagreement over which tactic they feel is more efficient to employ in actualizing their shared end goal.

ARMM and the forthcoming Bangsamoro include only a slice of southwestern Mindanao as opposed to each group’s desire that the full island come under the entity’s control, and although the entirety of the Sulu Archipelago is incorporated in each construction, Palawan is completely omitted in both cases. It can be inferred that MNLF and MILF believe that a piecemeal, state-approved approach should be utilized in expanding their future domain, while BIFF and Abu Sayyaf obviously favor terrorist tactics and have total disdain for the Manila-based authorities. Additionally, if the Philippines grant Bangsamoro enough broad-based autonomy, it might become a moot point whether or not the entity ever gains formal independence, as aside from not having externally focused privileges such as its own foreign and defense policies, it’ll pretty much be independent in all other instances, especially over its domestic affairs. This would accomplish the de-facto independence that all four Moro groups have been agitating for in one capacity or another, with the only challenge then being over which method they should pursue in incorporating the rest of Mindanao and all of Palawan.

Moro On The March:

Palawan

The Moro movements, be they government-sanctioned or terrorist-designated, will have difficulty creating a pretext for absorbing the rest of Mindanao under their Bangsamoro control owing to the largely Christian identity that the rest of the island now embodies, but matters would be considerably easier with Palawan, which has a substantial Muslim minority along its southern coast. It should be noted that MILF gave up its Bangsamoro claim for southern Palawan in 2012 as part of its peace talk arrangement with the government, but this doesn’t mean that it can’t be reactivated at a given time in the future, especially considering that the Muslim-majority demographic presence in that part of the island obviously wasn’t impacted by the group’s tactical political decision.

In a possible vision of the future, Palawan Muslims might engage in or be provoked into Mindanao-like disturbances, a Color Revolution scenario, or even terrorist activity as part of a larger agitation campaign to join Bangsamoro. This would be especially destabilizing for the Philippines since Palawan forms the basis of the country’s claim to the contested South China Sea islands, and a Muslim insurgency or outright terrorist war could have debilitating consequences for the viability of Manila’s maritime reach. At the same time, however, the US might see a strategic opening in all of this to increase its presence in the island.

The Pentagon already plans to have access to both air and naval bases there as part of the “Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement” that was signed in spring 2014, and under the pretext of defending these facilities and/or assisting the Philippine forces with quelling the “terrorist” disturbances there (whether or not they actually get to the form of terrorism is moot, as they’ll undoubtedly be labelled that way out of political considerations), the US might even be offered access to a conventional ground base there as well. If this happens, then the US would be in a position to establish full military dominance over this island and its surrounding territory in the air, land, and sea domains, essentially transforming this geostrategic location into its primary springboard for projecting force into the southern reaches of the South China Sea.

Sabah

The internationalization of the Moros’ struggle could easily occur if the conflict migrates to Malaysia’s northeastern state of Sabah. If the reader calls, it was earlier touched upon that this part of Borneo used to be under the control of the Sultanate of Sulu, and that the disagreement over its current status is an official source of disagreement between Malaysia and the Philippines, the latter of which inherited the Sultanate and his heirs’ claims to the territory. Non-state actors have already created a precedent for interference in this spat through the early 2013 Invasion of Lahad Datu, during which hundreds of armed terrorists landed on the Malaysian state’s fringes in the name of the self-proclaimed Sultanate of Sulu Jamalul Kiram III and attempted to violently usurp control from the legitimate authorities. The standoff that this created eventually ended with the deaths of 68 people, and the regretful incident highlighted just how prone the far-flung state is cross-border destabilization from the Philippines.

The problem in this theater of potentially forthcoming conflict is twofold, since it involves both the inability of the Philippine authorities to assert law-and-order control in the Sulu Archipelago and the still-unresolved issue over Sabah’s status. As regards the first issue, it’s difficult for Manila to directly involve itself in Sulu affairs owing to the latter’s incorporation in ARMM and the soon-to-be-established Bangsamoro autonomous entity. If the central government presses too deep into Moro territory, be it mainland (island) or maritime, it could provoke a violent response from the locals and endanger the MNLF and MILF peace processes in Mindanao, which is arguably more important and of much more urgent concern to Manila than enforcing border control over its distant island provinces. Additionally, the Philippines don’t seem eager to drop their formal claim, and with Malaysia not budging over its sovereign rights to Sabah, a diplomatic deadlock has most certainly set in. This creates a deficit of trust between the two sides and could contribute to an immediate escalation of bilateral military hostility if another border provocation takes place.

Seen from this perspective, it’s possible to predict that Bangsamoro’s formal incorporation, concurrent with Manila’s receding influence in the newly created territory, could create a destabilizing combination where non-state actors such as the self-proclaimed Sulu Sultanate’s heirs take the lead in unilaterally and more regularly trying to resolve the stalled dispute. Raising the stakes even more would be if the Sulu-based Abu Sayyaf adopts this cause as part of its official ideological portfolio and declares a jihad against Malaysia. The ISIL-affiliated group might even try to emulate its organizational role model’s style and opt for a formal method of territorial aggrandizement in replicating the 2013 Invasion of Lahad Datu. If it attempts such a move and actually makes landfall, then the Malaysian security services might somewhat justifiably accuse the Philippine authorities of negligence in allowing the terrorist group to launch a raid from their official territory, however autonomous it legally is. This would only contribute to the further collapse of bilateral ties and raise tensions between the two ASEAN member states. The Philippines could feel pressured to intervene in the Sulu Archipelago in order to prevent a similar attack, and this would of course inflame the Bangsamoro autonomous authorities. In another variation of this scenario, Malaysia might be tempted to stage its own limited intervention, which would then set off a surefire conflict escalation with the state and non-state actors in the Philippines.

The Bangsamoro Republik

In a startling timing of events, not even half a year after the Invasion of Lahad Datu, the leader of the MNLF declared the Bangsamoro Republik and prompted the Zamboanga City Crisis. Nur Misuari and his group only controlled a small fraction of the territory that they unilaterally claimed, but all in all, their proposed country was envisioned as comprising all of the proposed Bangasamoro areas (southwestern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago), the rest of Mindanao, Palawan, and Sabah. In sum, what was purportedly the most ‘mild’ of the Mindanao militant groups made a far-reaching power play for everything that it and its three counterparts were hoping for, although it was ultimately in vain. What’s important, however, was that the MNLF played its hand and showed the full extent of the territory that it and the others have been after all along, despite the incoherence over their tactical disputes. This left no doubt in the minds of many that the Moro militants would eventually make a move on Palawan and Sabah, whether in concert with one another or independently thereof, sometime after the formalization of Bangsamoro.

The Mindanao-Sulawesi Arc:

The most disruptive manifestation of the Moro insurgency would definitely be its spread into Palawan and Sabah, but it’s possible for the chaos that this generates to make the leap into Indonesia as well. Speaking at the Shangri-La Dialogue in May 2015, Francisco Acedillo, a member of the Philippine House of Representatives, warned against “ISI[L] gaining a foothold in what we would call the Mindanao–Sulawesi Arc.” The Moro militants already have a transnational expansionist plan in regaining control over the Sulu Sultanate’s North Borneo holdings, and the terrorist members among them (Abu Sayyaf and BIFF) have close ties with the Indonesian jihadist group Jemaah Islamiyah.  Abu Sayyaf is literally fighting side-by-side with them in Sulu while BIFF is reportedly being trained by them, so this creates an international nexus of terrorism as it is. Another issue to take into consideration is that the Philippines-based terrorists are also aligned with ISIL, and it was just spoken about how the ‘caliphate’-building project could be easily transplanted to Southeast Asia by superimposing it over the Moro claims to Palawan and Sabah, and, provocatively enough, perhaps even linking it together with Jemaah Islamiyah’s ambitions in Indonesia.

Abu Sayyaf is literally fighting side-by-side with them in Sulu while BIFF is reportedly being trained by them, so this creates an international nexus of terrorism as it is. Another issue to take into consideration is that the Philippines-based terrorists are also aligned with ISIL, and it was just spoken about how the ‘caliphate’-building project could be easily transplanted to Southeast Asia by superimposing it over the Moro claims to Palawan and Sabah, and, provocatively enough, perhaps even linking it together with Jemaah Islamiyah’s ambitions in Indonesia.

On the surface, one would be inclined to doubt the last scenario of a linkup between ISIL-affiliates Abu Sayyaf and BIFF and Al Qaeda ally Jemaah Islamiyah due to their patrons’ heated rivalry with one another, but technically speaking, they do have overlapping and complementary objectives in Southeast Asia that would best be served by a tactical alliance. Another thing to keep in mind is that Southeast Asia, despite having fallen victim to terrorists in the past, isn’t as much of a ‘conventional’ frontline region as the Mideast and Afghanistan are, for example, meaning that the competition between these two terrorist ‘franchises’ might not be as severe and bloody as what they’re experiencing in those aforementioned two theaters. This leaves open the opportunity for an unprecedented alliance between them, even if this isn’t officially sanctioned by either of their respective leaderships. Being located so far away from their ‘corporate’ terrorist centers, these Southeast Asian ‘franchises’ are relatively free to do as they please, and there’s never been any hard evidence confirming the degree of closeness that they have with their ‘headquarters’ in the Mideast. Although regional fighters have received their terrorist training in this theater or Afghanistan, they might not be as directly controlled by their proclaimed patrons as people may think, thus giving them the operational freedom to make an ‘unholy’ alliance with their regional peers irrespective of the ISIL-Al Qaeda rivalry.

In the event that the examined scenario of a Philippine-Indonesian terrorist alliance is ever actualized to some degree, then it would by far be the most internationally disruptive event to occur in insular ASEAN’s recent history, especially if it dragged in Malaysia, as has been anticipated. It’s not to say that this scenario is probable in the immediate term, but that it convincingly seems ever more likely as largely autonomous Bangsamoro enters into fruition and Southeast Asian-originating jihadists return home from the Mideast and Afghanistan. The emergence of a black hole of chaos in this distant corner of ASEAN would be troublesome for every actor involved, as they each have more prioritized locations to protect than these far-off regions: the Philippines must secure the rest of mainland Mindanao, Palawan, Luzon, and the Visayas; Malaysia must look after the more populous and economically productive peninsular part of the country; and Indonesia must struggle to secure Sumatra and Java, the population and economic centers of the island nation. Thus, an outbreak of chaos ringing the Sulu and Celebes Seas would strike at the blind spot of each of these three countries and hit them in the most multilaterally destabilizing manner possible and instantly disrupt the application of whatever other policies they were pursuing up until that time.

Malaysia

The federal state of Malaysia is vulnerable to more destabilization scenarios than just the Philippines-originating “Greater Moro” one, although that in and of itself has the capability of being a crippling crisis on its own. The other possibilities facing its leadership are a stereotypical Color Revolution (with the Chinese minority being tricked into playing a leading role) and the cross-border terrorist issue with southern Thailand. A breakdown of order in Malaysia could have immediate global consequences because the country is a financial hub for Southeast Asia and part of its territory is critically located along the Strait of Malacca. Anti-government protests here typically make the global news in some capacity or another (although usually not as the main headline event of the day), showing just how highly foreign observers value the country’s stability due to the aforementioned reasons.

Historical Backgrounder:

General Information

Malaysia has a very rich history, but for the context of the research, only its recent past after independence is relevant. Still, it’s worthwhile to add a few words about its civilizational legacy because of the broad impact that it’s had on the region. The Malay people were part of the Indianized Srivijaya Empire that existed from the 7th to the 14th centuries, and afterwards they led the Malacca Sultanate that sprouted up in its wake. In both instances, Peninsular Malay (in which the majority of the contemporary population and economy are based) was the gateway for foreign influences to enter the larger Southeast Asian archipelago, be it the Indonesian islands or the Philippine ones further afield. At the same time, there was also a diffusion of other cultures into the peninsula as well, and it’s for this reason why Indonesian can be considered as mutually intelligible with Malay language. The similarities between Malay and Tagalog (officially called the Filipino language) are less evident due to a variety of factors, but nonetheless, they still exist to a small extent. All of this information is useful in grasping the historical interconnection of soft power elements between the modern-day states of Southeast Asia since each of them still engages with one another to an ever-increasing extent, which is only expected to grow with the formation of the ASEAN Economic Community.

Malaysia has a very rich history, but for the context of the research, only its recent past after independence is relevant. Still, it’s worthwhile to add a few words about its civilizational legacy because of the broad impact that it’s had on the region. The Malay people were part of the Indianized Srivijaya Empire that existed from the 7th to the 14th centuries, and afterwards they led the Malacca Sultanate that sprouted up in its wake. In both instances, Peninsular Malay (in which the majority of the contemporary population and economy are based) was the gateway for foreign influences to enter the larger Southeast Asian archipelago, be it the Indonesian islands or the Philippine ones further afield. At the same time, there was also a diffusion of other cultures into the peninsula as well, and it’s for this reason why Indonesian can be considered as mutually intelligible with Malay language. The similarities between Malay and Tagalog (officially called the Filipino language) are less evident due to a variety of factors, but nonetheless, they still exist to a small extent. All of this information is useful in grasping the historical interconnection of soft power elements between the modern-day states of Southeast Asia since each of them still engages with one another to an ever-increasing extent, which is only expected to grow with the formation of the ASEAN Economic Community.

Relevant Post-Independence Facts

The modern-day territory of Malaysia used to only comprise the peninsular portion of the country, and the entity wasn’t even officially termed “Malaysia” until 1963. The Malay Union is the name of the polity that emerged in 1946, but it was quickly transformed into the Federation of Malaya two years later. From 1948-1960 it underwent a violent communist insurgency known as the Malayan Emergency that required the heavy participation of British troops to quell, and this disturbance was prominently led by the Chinese minority in the country. These citizens have always felt ostracized by the authorities, and their particular situation as it relates to the present will be discussed later on. To continue, the counter-insurgency methods utilized during that time are still noted to this day as being among the most effective, and their successful implementation created the conditions where the British felt comfortable enough granting the Federation of Malaya its independence in 1957.

It wasn’t until 1963 that the modern borders of Malaysia and the name of the country itself came into play. That was the year when Sarawak, North Borneo (now called Sabah), and Singapore joined the Federation of Malaya, which then became Malaysia. Internal disputes led to Singapore’s expulsion in 1965, but other than that, the newly formed country’s borders have remained intact since that time. Of strategic pertinence, Kuala Lumpur’s newly acquired control over most of the northern coast of Borneo entitled it copious oil and gas reserves that would later be used to help fund the country’s development. Petronas, the national resource company that was founded in 1974 to extract and manager these deposits, would soon thereafter go on to become a prominent name in the industry. This only underscores the value that the underpopulated but resource-heavy eastern regions of Malaysia have to the federal government in Kuala Lumpur, and it goes to show that they’ll be protected at all costs despite their distance from the core of the country.

It’s also important to highlight that Malaysia’s 1963 formalization produced a very negative reaction in Indonesia and the Philippines, with the former believing that it had the right to control all of Borneo while the latter laid claim to North Borneo owing to the disputed treaty that it inherited from the Sulu Sultanate (and which was just discussed previously). Indonesia’s reaction to the creation of Malaysia was to commence a tense period of what was then known as “Konfrontasi”, while the Philippines’ was to attempt the failed destabilization of Sabah, which culminated in the tragic Jabidah Massacre. Despite the Philippines retaining its claim even after then, for the most part, Malaysia’s neighbors worked past their differences in the mid-1960s to the point where they peacefully proclaimed ASEAN in 1967. It should be remarked, however, that Indonesia’s change in policy was heavily influenced by the CIA-influenced coup against then-President Sukarno, and that without Suharto’s rise to power, Konfrontasi may have lingered for a few years longer or might never have been repealed. Therefore, one could draw an inferred connection between the CIA coup in Indonesia and the subsequent founding of ASEAN, and it’s worthy to note at this junction that the organization was vehemently anti-communist, so there may be more to its American-suspected origins than initially meets the eye.

Filipino Fracas:

To present as smooth of a continuum as possible, the Malaysian segment of the scenario research will pick up where the Philippine portion left off and continue discussing the possible destabilization of Sabah state. The Philippines don’t just have a territorial claim over the region, they’ve also settled it with many of their citizens via “refugee flows” to the area. It was ascertained in 2013 that 73,000 refugees entered Sabah from 1976-1985, driven away from their homes partly due to the intense fighting that was taking place in Mindanao at the time.  While there certainly are humanitarian reasons for their exodus, it can’t be ignored that this was still a large influx of Philippine citizens into a disputed area that continues to be claimed by Manila. To be fair, corrupt Malaysian authorities were responsible for crafting various pull incentives in the 1990s via the “Project IC” scam, whereby identity cards (IC) were given to “refugees” solely for the purpose of adding them to voting rolls and tilting local elections in a predetermined direction. The mixture of legitimate humanitarian push factors caused by the Mindanao Conflict, the Philippine government’s implicit colonization agenda, and Malaysia’s own corruption contributed to producing a situation where Filipino refugees/migrants are a problem in eastern Sabah state.

While there certainly are humanitarian reasons for their exodus, it can’t be ignored that this was still a large influx of Philippine citizens into a disputed area that continues to be claimed by Manila. To be fair, corrupt Malaysian authorities were responsible for crafting various pull incentives in the 1990s via the “Project IC” scam, whereby identity cards (IC) were given to “refugees” solely for the purpose of adding them to voting rolls and tilting local elections in a predetermined direction. The mixture of legitimate humanitarian push factors caused by the Mindanao Conflict, the Philippine government’s implicit colonization agenda, and Malaysia’s own corruption contributed to producing a situation where Filipino refugees/migrants are a problem in eastern Sabah state.

In the future, it’s conceivable that this expatriate community could form a vanguard force in destabilizing the rest of the province, or at the very least, in welcoming and assisting any Sulu-originating invaders (perhaps led by Abu Sayyaf). Additionally, community-wide disturbances by this demographic could provoke the Malaysian security forces into a resorting to violence or a large-scale deportation operation, both of which could then be manipulated by the American-influenced global media into “Malaysian aggression” against “Filipino refugees” as part of a larger information campaign against Kuala Lumpur. The “humanitarian”-centric narrative that predominates the unipolar media wouldn’t be able to resist falling for the tempting bait of maligning Malaysia’s name, and it might even hit such a feverish pitch that the anti-government message sets a preplanned Color Revolution attempt into motion. No matter if it gets that far or not, the scenario of Malaysian-on-Filipino violence (whether stage-managed or of legitimate concern) would certainly be met with harsh consternation from Manila and as sharp of a rebuke as possible, leading one to believe that the entire incident could be prompted by outside forces that are interested in seeing a deterioration of Malaysian-Philippine relations.

Overall, the significance of the Sabah region to Malaysia is that it represents an exceedingly vulnerable frontier that’s susceptible to terrorist infiltration and Color Revolution provocations. This means that it could possibly become the scene of a low-intensity Hybrid War, whereby social agitation quickly gives way to anti-government violence. Even if it isn’t sustainable in the long-term and is extinguished just as quickly as the terrorist invasion of early 2013, it could still be strategically offsetting for the state if it’s timed to coincide with another incidents of violence elsewhere in the country. Like what was mentioned earlier, it might turn out that a Filipino fracas in Sabah might just be a signal to jumpstart a Color Revolution in Kuala Lumpur and keep the security establishment’s attention divided so as to facilitate the more serious destabilization in the capital. Malaysian-on-Filipino violence could become a symbolic incentive for Chinese Malays to take to the streets in protest, especially as they’re already concerned about being discriminated against themselves and were at the forefront of the last major anti-government rallies in September 2015. Accordingly, it’s now appropriate to transition the research in the direction of exploring this group’s role in any forthcoming Color Revolution attempt, whether it’s connected to destabilization in Sabah or separately initiated.

The China Card:

Background

Unless one is native to Malaysia, ethnic Chinese themselves, or they’re already familiar with the country’s demography, most people would be surprised to learn that 24.6% of the population is Chinese and that just most them are concentrated in Peninsula Malaysia. Proportionally speaking, the Chinese are also the third-largest plurality in Sarawak at about 22% of the population, but their 585,000 ethnic compatriots pales in comparison to the many millions more that reside in the western reaches of the country. This identity group has technically been present in the area for centuries, but it wasn’t until the 20th century that significant enough migration occurred to give them a strong stake in the country’s overall population metrics. For the most part, the Chinese community was relatively successful in Malaysia and came to occupy a privileged position in the overall economy due to their trade links and investment capital. Since the end of World War II and the beginning of the Malayan Emergency in 1948, the Chinese population fell victim to discriminatory policies motivated by the fact that this ethnic category incommensurately contributed to more communist insurgents than any other. Another issue was the widespread perception that the British colonizers favored this group over the ethnic Malay majority, which is in accordance with the Crown’s stereotypical divide-and-rule approach.

The Breaking Point

Tensions between the two communities hit a climax during the deadly race riots of 1969, after which the government implemented an affirmative action policy designed to enable the Malays to gain a more proportionate foothold in the economy. With time, the Chinese began to allege that this policy had turned into an anti-minority discriminatory regime that was keeping non-Malays in a position of indefinite second-class status. The reality is of course a lot more complex than this simple summary can provide for in the context of the Hybrid War discussion, but what’s noteworthy for the reader to remember is that Chinese-Malay intercommunal relations have progressively gotten worse over the past few decades. This isn’t inconsequential either, considering that the Chinese constitute nearly a quarter of the population and have the potential to harness deep reserves of social and economic capital in the event of an anti-government revolt.

Tensions between the two communities hit a climax during the deadly race riots of 1969, after which the government implemented an affirmative action policy designed to enable the Malays to gain a more proportionate foothold in the economy. With time, the Chinese began to allege that this policy had turned into an anti-minority discriminatory regime that was keeping non-Malays in a position of indefinite second-class status. The reality is of course a lot more complex than this simple summary can provide for in the context of the Hybrid War discussion, but what’s noteworthy for the reader to remember is that Chinese-Malay intercommunal relations have progressively gotten worse over the past few decades. This isn’t inconsequential either, considering that the Chinese constitute nearly a quarter of the population and have the potential to harness deep reserves of social and economic capital in the event of an anti-government revolt.

Sharia Law

Another relevant factor to bring up is that most Chinese are areligious and do not follow Islam, the privileged religion of Malaysia. In a country that selectively implements Sharia law, this could be troublesome to both the majority and the minority. On the one hand, the piously abiding Malays may become offended at some of the behavior exhibited by the Chinese community, feeling it’s extraordinarily disrespectful for non-Muslims to not abide by or respect certain Islamic statutes. On the other hand, however, the Chinese may feel uncomfortable knowing that there’s a separate legal system for Muslims and non-Muslims, and this could enhance the feeling of separateness that they feel towards the state and the majority ethnic group that comprises it. This doesn’t only relate to the Chinese, however, as secular Malays, however much of a minority of the population that they are, are also somewhat at odds over Sharia law. For example, a secular activist who made a viral video in spring 2015 mocking a proposal to extend Sharia law to yet another province was investigated by the police for blasphemy and sedition. One can only imagine the type of communal uproar that might have happened if the individual was Chinese and their ethnic affiliates started rallying against the government in response.

Foreign Manipulation

The previously mentioned information clearly points in the direction of preexisting Malay-Chinese tensions that could predictably be exploited by foreign powers. China’s policy of non-interference indicates that it’s not likely to use this ethnic card to its geopolitical advantage, and not only that, but it wouldn’t have much to substantially gain even if it decided to do so. Foreign media and intelligence agencies (sometime one and the same organization) are already scrupulously investigating any rumored link that China may have to Southeast Asian protest movements, be it the anti-government events that led to the 2014 military coup in Thailand or the more recent half-hearted Color Revolution attempt in Malaysia (which will be commented upon soon). Anytime there’s any event whatsoever that could be speculatively pinned on China, the unipolar media will jump at the chance and try to do so, expending whatever effort is necessary in order to find even a smidgeon of circumstantial ‘proof’ behind the occurrence. In an environment of such intense scrutiny, China has nothing to gain and everything to lose if it took to the path of mischievously contracting its diaspora to carry out its foreign policy objectives in whichever state it may be. It’s of course very possible that the independently organized actions of ethnic Chinese activists could coincide with Beijing’s particular strategy in certain states, but in that case it’s more of a coincidence of action and less the fulfillment of a given command.

What makes China’s Southeast Asian diaspora especially interesting is that there’s the possibility that elements of this community could fall under foreign influence and be used in false-flag events to implicate China. To elaborate a little bit, with the prevailing presumption being that the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia and elsewhere could be political pawns of the Chinese Foreign Ministry (no matter how false this narrative actually is, just as it’s alleged about the Russian diaspora in some countries), whatever political actions they engage in can become fodder for besmirching Beijing. The US’ unipolar-aligned information services would go into overdrive in their campaign to link the protesters with China, even going as far as propagating unfounded rumors alluding to this connection, all in an attempt to delegitimize whatever the cause is that they’re protesting around and/or to spread the myth that China is ‘interfering’ in the foreign affairs of its neighbors. The first element could be used to discredit authentic protest movements before they have the chance to become popular among the titular majority and affect tangible change, while the second strategy could be called upon to provoke tension between China and the targeted nation. In light of ethnic Chinese taking the forefront role in organizing the recent Color Revolution unrest that plagued Malaysia, the connection between this group and the unwitting manner in which they were exploited by the US deserves to be expanded upon on in order to understand the direction that this dynamic is headed.

The latest Color Revolution deployment in Southeast Asia took place in Malaysia during the months of August and September 2015. The cause for the event was relatively benign, motivated by corruption allegations against Prime Minister Najib Razak, with many in the Chinese Malaysian community siding with the protesters while the majority Malay stood with the government. The resultant Malay-against-Chinese standoff that developed thankfully didn’t descend into the violence of 1969, but it once more brought identity tension to the surface, albeit under a thin veneer of political differences. To recall the author’s earlier comments on the topic, there are irrefutably legitimate reasons for the Chinese Malaysians to be upset against the government and the ethnic majority in the country, but by and large, they hadn’t significantly organized as a unified identity bloc against the authorities until then. In hindsight, one can state that while the “Bersih 4” movement was ultimately unsuccessful in its regime change demands, it did achieve quite a lot in unifying the Chinese diaspora under a semi-integrated political banner, and it’s this accomplishment which presents the most profound Color Revolution threat in the future.

Ethnic Malays may now be under the impression that the Chinese community is inherently anti-government, thereby making it a sort of ‘sleeper cell’ that can be reactivated when need be. The distrust that this creates is perilous for Malaysia’s multiethnic society and will inevitably lead to a further distancing of interethnic relations in the future, provided of course that the present trajectory continues (and there’s no indication that this decades-long process will be reversed anytime soon). On a geopolitical level, ethnic Malays and some of their governing officials may have associated the mostly Chinese-comprised protests as being part of a larger policy of supposed South China Sea ‘destabilization’ by Beijing, guided towards this false conclusion by the US and its allied media outlets operating in their country. The Chinese Ambassador’s principled statements against racism in Malaysia were perverted into a message of “interference” into the country’s internal affairs, thereby proving how eager some media outlets are to warp the words of Chinese representatives, regardless of how apolitical and common sense-driven they may be. Fortunately for Kuala Lumpur-Beijing relations, it doesn’t appear as though the Prime Minister or his cabinet fell for the deceptive media image and blamed China for the unrest, but the fact remains that civil society is more divided than ever because of this, and that’s of course going to remain a major problem and source of potential trouble.

On a different international tangent than the one just described, the Bersih 4 movement also attempted to unify international civil societies. The organization called for ‘support rallies’ all across the world, encouraging Malaysians to demonstrate in their respective diaspora communities. Particular attention should be drawn to the planned gatherings that were supposed to be held in China, Thailand, and Singapore, but thankfully were cancelled by the authorities before they could take place. In each of these states, the target audience that the protesters wanted to invite to their event was undoubtedly the ethnic Chinese. Aside from the obviousness for why this relates to China itself, around 14% and 76% of Thailand and Singapore, respectively, are composed of ethnic Chinese. Clearly, the Bersih 4 wanted to draw this group into the protest in order to provoke the ethnic Malay into thinking that the most prominent regional Chinese communities were against their legitimate government. The purpose of this stunt was none other than to deepen the trust divide between these two ethnic communities and to create a source of tension for bilateral relations between Malaysia and whichever country it would have been that would have allowed the ethnic Chinese-comprised protests to go forward. Wiser heads thankfully prevailed and the events were banned in each of these three countries, but that in and of itself could have also been a trigger for collateral preplanned destabilization if the purported ‘activists’ decided to protest against their own governments in response. That scenario didn’t come to pass, but the strategic likelihood of it occurring in the future during another forthcoming Chinese-driven anti-government protest in Malaysia can’t be ignored.

Color Revolution And Chinese Overview

Overall, it can be ascertained that the Chinese Malaysian community is a viable political force that has yet to flex its full political muscle, with recent events showing what it’s capable of but stopping just short of a being a full-fledged Color Revolution attempt. This can be interpreted partly by the fact that the ethnic Malays constrained themselves from carrying out the ethnic pogroms that some actors were goading them into, but also by the stereotypical discipline of the Chinese in refusing to get totally carried away with their protest activity. The social chasm that exists between the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups hasn’t disappeared, and if anything, it only widened in the months since the disturbance took place. It’s therefore possible for a repeat of these events to occur, where the Chinese lead an anti-government protest movement against the legitimate ethnic Malay authorities. To reemphasize what the author has said before, the Chinese do have sincere grievances, but their social capital appears to have been exploited by an external actor (i.e. the US) that was interested in a low-level Color Revolution test run as opposed to a diehard desire to commit regime change. If it really was the case that the external organizer (whose role most protesters were unaware of) really wanted to overthrow Prime Minister Razak, then it’s probable that a larger-scale destabilization would have unfolded.

To explain the movement’s progressive diminishment, it’s worthwhile to remember that the US is always experimenting with different Color Revolution tactics, and the recent trend as judged by events in the Republic of Macedonia, Armenia, and then Malaysia has been to use so-called “corruption” allegations and “civil society causes” to provoke anti-government movements. The previous template had always been to use a dramatic, tangible, and timed event such as elections in producing this effect, but the field data gleaned from these three aforementioned scenarios proves that Color Revolutions could be summoned on command through the ‘convenient’ disclosure of a supposed corruption scandal or a heightened emphasis on an existing controversial issue (such as Armenia’s electrical grid). Also, the events in Malaysia cannot be interpreted outside the large geopolitical context in which they occurred, which is the US’ Pivot to Asia and New Cold War containment policy against China. It becomes increasingly clear that the US may have wanted to put pressure on Prime Minister Razak in order to compel him to agree to the TPP’s controversial conditions, seeing as how his country had been one of the few that stalled the trade pact’s negotiations in late July. Unsurprisingly, after the Bersih 4 Color Revolution scare, Malaysia agreed to the TPP shortly thereafter in early October.

Thai Trouble:

The last destabilization scenario that could realistically wrack Malaysia sometime in the future deals with the militant problem along the Thai border. In order to fully understand all of the factors at play here, the reader needs to be briefly educated about the conflict’s history. This issue principally involves Thailand, but because of the potential for escalatory cross-border violence in Malaysia, some commentary needs to be given about it at this time. To broadly simplify the situation, a few southern Thai provinces are populated mostly by Malay Muslims and identify substantially less with Buddhist Bangkok than they do with their ethnic co-confessionalists in Kuala Lumpur. There’s also the tricky issue of how and why Thailand has maintained its rule over these Muslim-majority reasons, which basically boils down to a late-18th century military conquest that was recognized by the British in the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. It was after this international legitimization that Bangkok upped its presence in the provinces from one of extracting tribute to actual Thaification.

The last destabilization scenario that could realistically wrack Malaysia sometime in the future deals with the militant problem along the Thai border. In order to fully understand all of the factors at play here, the reader needs to be briefly educated about the conflict’s history. This issue principally involves Thailand, but because of the potential for escalatory cross-border violence in Malaysia, some commentary needs to be given about it at this time. To broadly simplify the situation, a few southern Thai provinces are populated mostly by Malay Muslims and identify substantially less with Buddhist Bangkok than they do with their ethnic co-confessionalists in Kuala Lumpur. There’s also the tricky issue of how and why Thailand has maintained its rule over these Muslim-majority reasons, which basically boils down to a late-18th century military conquest that was recognized by the British in the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. It was after this international legitimization that Bangkok upped its presence in the provinces from one of extracting tribute to actual Thaification.

To speed through decades of simmering discontent, Thailand stoked the flames of nationalist and religious fury by annexing several northern Malaysian provinces during World War II. After its Japanese-sponsored Axis conquests were rescinded at the end of the war, some of the Malaysian Muslims still living in pre-World War II Thai-administered territory were aggrieved that they weren’t able to also free themselves from Bangkok. A separatist struggle broke out afterwards that was largely put down in the ensuing years, but the memory of perceived and unfair occupation remained and the identity separateness of Thailand’s southern provinces from the rest of the country only widened since. Being that religious differences laid at the forefront of the region’s hostility to the central government, it was expected that Wahhabist terrorists would seek to exploit the conflict for their own purposes, slyly disguising their true motives behind a cover of ‘ethnic separatism’ and other more plausibly acceptable slogans than militant jihad. The astute observer can identity quite a few structural similarities between this conflict and the one in Mindanao, as both may have started as justified protests against their respective central governments, but unfortunately devolved into terrorist outbursts that have completely discredited most of the legitimacy that they may have previously enjoyed.

The present state of play is that a large military presence is needed to keep the peace in the southern provinces, as the explosion of terrorism in the mid-2000s sent a shock down the spine of the entire Thai establishment. Malaysia is interwoven into this dispute whether it knowingly wants to be or not because of the religious and ethnic similarity that it has with the southern Thai insurgents, to say nothing of the mutual border between them. It’s not to suggest that Malaysia is currently supporting the movement or is in favor of using the scourge of Islamic terrorism to promote suspected irredentist ends, but that it is bound to be affected by the conflict in one way or another. The heavy Thai military presence in the south may prompt a situation where overzealous recruits chase suspected terrorists across the border into Malaysia or fire their weapons into its territory, thus sparking a scandal or perhaps even an outright crisis.

Even if this doesn’t happen, if it is revealed or even suspected that the terrorists are enjoying some sort of safe haven on the Malaysian side of the border (whether government-sponsored, due to the state’s administrative neglect, and/or supported by non-state actors), then Bangkok might loudly make its claims public and attempt to put pressure on Kuala Lumpur. If substantiated or convincing enough, then this could lead to Malaysia’s relative isolation from its neighbors and sow the seeds of distrust into ASEAN. Another consequence could be Thailand and the Philippines diplomatically teaming up against Malaysia, each supporting their respective anti-Malaysian claims in parallel with the other. Finally, the last projected problem that could occur along this shared border could unfold if the Thai military makes a concerted push in the region and expels the terrorist groups that are still embedded within it. As these sorts of operations have a tendency for doing, they could also engender a refugee crisis as well, and the cross-border population flows that enter Malaysia could upset the existing balance in its northern provinces. Not only that, but if some of the terrorists use the refugee movements as a cover for infiltrating into Malaysia, then they could eventually rebuild their bases on that side of the border and truly usher in an international crisis if they one day strike Thailand from Malaysian territory.

Brunei And Singapore

These two tiny Southeast Asian states are typically overlooked by most analysts, owing largely to the fact that their physical reach doesn’t extent anywhere near as wide as their counterparts’. Leaving these two countries out of any regional analysis is a huge oversight, even if neither of them is all that susceptible to Hybrid War. In their own way, however, there are certain destabilization triggers that could be activated in the event of any forthcoming asymmetrical hostilities, and it’s these factors which deserve a few moments of commentary.

Brunei:

The smallest state in Borneo, the Sultanate of Brunei used to be a sizeable empire that controlled the entirety of the island’s coast. It even exercised sovereignty over the Sulu Archipelago, Palawan, Mindoro, and the extreme western portions of Luzon and Mindanao. Its heyday is long gone, but its legacy remains firmly in the minds of the country’s ruler and its citizenry, and it would be curious to observe whether they attempt to revive their glorious past in one form or another in the event that Malaysia’s Sarawak and/or Sabah states are destabilized to some extent in the future. The shrunken sultanate that remains in the present day is largely dependent on oil and gas exports, and its miniscule population (fewer than half a million people) means that the trappings of this exorbitant wealth remain heavily concentrated and easily visible for all to see.

The smallest state in Borneo, the Sultanate of Brunei used to be a sizeable empire that controlled the entirety of the island’s coast. It even exercised sovereignty over the Sulu Archipelago, Palawan, Mindoro, and the extreme western portions of Luzon and Mindanao. Its heyday is long gone, but its legacy remains firmly in the minds of the country’s ruler and its citizenry, and it would be curious to observe whether they attempt to revive their glorious past in one form or another in the event that Malaysia’s Sarawak and/or Sabah states are destabilized to some extent in the future. The shrunken sultanate that remains in the present day is largely dependent on oil and gas exports, and its miniscule population (fewer than half a million people) means that the trappings of this exorbitant wealth remain heavily concentrated and easily visible for all to see.

Brunei doesn’t have much of a military to speak of, but it allowed the British to retain their basing rights after the country’s 1984 independence, and the UK currently has around 2,000 troops presently stationed there. The “special relationship” that the US enjoys with the UK essentially provides it privileged access to Brunei as well, and the Pentagon and its Bruneian counterparts regularly stage interoperability drills. From the geopolitical perspective, this territorially miniscule state is exceptionally strategic because of its position along the southern reaches of the South China Sea, and with the US engaging in the Pivot to Asia, its importance is only expected to spike in the coming years.

In terms of self-identity, the vast majority of Bruneians are Muslim and the country has been administered under Sharia law since 2014, but the issue that emerges is that the majority of guest workers in the country don’t follow that religion. The Diplomat cites that “Thirty-two percent (of the population) are non-Muslim made-up largely of foreign workers, many of them from the Philippines, which is predominantly Catholic”, thus setting the stage for potential conflict between the local natives and foreign workers. Brunei’s ruler has the sovereign right to govern his country as he sees fit, but his banning of Christmas celebrations in the sultanate has provoked global outrage, scorn, and mockery, indicating that powerful international forces are intent on stirring up the pot of trouble and casting an extremely negative light on the country.

The 2015 holiday celebrations passed without incident, but there’s always the possibility that each future Christmas might create a pretext for the Filipinos or other Christian-identifying migrant workers to protest and spark a domestic debacle, especially if they’re goaded into violence by various foreign influences (media, NGOs, etc.) and the state is compelled to crack down on them. It’s difficult to project the direction that the forecasted conflict could take because its dynamics would be totally unprecedented, but if the brief and unsuccessful 1962 Brunei Revolt is any indication, then the British will possibly play a decisive role in stopping the uprising. The US could also supply additional support to the government in the aftermath of the disturbance in order to entrench its position along the southern rim of the South China Sea.

Singapore:

The smallest state in ASEAN and one of the tiniest in the world, Singapore punches well above its weight in geopolitical affairs. Located in the ultra-strategic Strait of Malacca, its position gives it leverage over the chokepoint through which almost all East-West maritime trade between the two sides of Eurasia must pass. Singapore has exploited its advantageous location in order to become a bustling economic and financial hub, and the city-state is recognized as one of the most affluent places in the world. When it was expelled from the Malaysian Federation in 1965, many observers doubted that the island backwater would ever become stable and successful, but the visionary leadership of Lee Kuan Yew ensured that Singapore’s future would be secure.

The smallest state in ASEAN and one of the tiniest in the world, Singapore punches well above its weight in geopolitical affairs. Located in the ultra-strategic Strait of Malacca, its position gives it leverage over the chokepoint through which almost all East-West maritime trade between the two sides of Eurasia must pass. Singapore has exploited its advantageous location in order to become a bustling economic and financial hub, and the city-state is recognized as one of the most affluent places in the world. When it was expelled from the Malaysian Federation in 1965, many observers doubted that the island backwater would ever become stable and successful, but the visionary leadership of Lee Kuan Yew ensured that Singapore’s future would be secure.

The father of the nation, as he can rightfully be called and is popularly recognized as, was a proponent of the strong state method of development, whereby the government plays the guiding role in all national affairs. The concept of “liberal democracy”, as it’s commonly understood in the West, is not only foreign to Singapore, but also structurally taboo, as its official implementation would have derailed the Zen-like focus for the country to prosper during its darkest days of early development. Even today, “liberal democracy” is frowned upon by the state and is seen as a dire threat to Singapore’s future. The country’s Western partners continually apply soft pressure on it to move in the direction of their favored governing model, and unipolar-influenced media have been taking steps to inform the world of the “undemocratic” practices prevalent in the country.

At the same time, they (and chief among them, the US) know that the most important thing is to keep Singapore as an ally no matter what disagreements they may have about internal governing procedures, although the genie of “liberal democracy” that they’ve been trying to let loose could eventually result in unexpected turmoil if ‘rogue’ NGOs and their radical followers stir up trouble at an ‘inopportune’ time. Singapore’s pro-Western trajectory and domestic stability are what the US cares about more than anything, and it has a stake in the island’s success due to the strategic partnership between the two. Accordingly, it’s not expected that it will support any NGO-organized clashes within the country, although it might stand to benefit from a few low-intensity engagements between them and the security forces if this can somehow be blamed on China.

The US’ interests in Singapore transcend the economic sphere (embodied by their shared TPP membership) and incorporate elements of the anti-Chinese containment strategy, which is why it’s so pivotal that the US maintain its good standing with the island state. The US officially plans to base four warships in the country by 2018, but in all probability, it’ll likely have many more assets there than that in the coming future. The end of 2015 saw Singapore agreeing to host US spy planes too, despite the Pentagon’s intention that they’ll explicitly be used for gathering intelligence about China’s activities in the South China Sea. These military-strategic imperatives occupy a higher place in the US’ list of priorities than Singapore’s supposedly “undemocratic” form of governance, and it stands to reason that Washington won’t ever let its ideological objectives get in the way of its pragmatic pursuit in sustaining unipolarity there.

Andrew Korybko is the post-graduate of the MGIMO University and author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China (V) | Protestation

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China (V) | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: The Philippines' pivot in action: Can 'The Punisher' withstand America's punishment? | 2RUTH.NETWORK

Pingback: Le pivot des Philippines en action: le « Punisseur » peut-il résister à la punition US? | Réseau International

Pingback: The Philippines’ pivot in action: Can “The Punisher” withstand America’s punishment? | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: What Would Happen if Duterte Implemented A “Revolutionary Government”? | OrientalReview.org

Pingback: Que se passerait-il si Duterte mettait en œuvre un « gouvernement révolutionnaire » ? | Réseau International

Pingback: Malaysia’s Fake News Law Is Likely To Backfire – Webstynx

Pingback: Mahathir Will Proceed Malaysia’s Multipolar Course – ICEPI TEXT NEWS

Pingback: Mahathir Will Proceed Malaysia’s Multipolar Course – Webstynx

Pingback: Prime Minister Mahathir Will Continue Malaysia’s Multipolar Course – Viralmount

Pingback: 2019 Forecast for Afro-Eurasia - XPBET

Pingback: Prévisions 2019 pour Afro-Eurasia – Future Eurasia – DE LA GRANDE VADROUILLE A LA LONGUE MARGE

Pingback: 2019 Forecast For Afro-Eurasia | Réseau International (english)