(Please read Part I prior to this article)

The Unipolar Transition

Structural And Social Preconditioning:

Although the Saffron Revolution failed in achieving its regime change goals, what it did succeed in was sending an ominous warning sign to the Myanmar generals of the sort of destabilization scenarios that they could expect in the coming future if they don’t begin reorienting towards the US. By enacting even more sanctions against Naypyidaw than they previously had, the Western community inversely increased Myanmar’s dependence on China, although this time, it appears to have been done with that presumed reaction in mind. The US and its affiliated information organs would soon thereafter begin promoting the media narrative that Myanmar is becoming adversely dependent on China to the point of resembling a satellite state, knowing that this rhetoric would frighteningly resonate to some extent or another with the country’s military leadership. Myanmar had only entered into strategic relations with China owing to immediate international circumstances, and it was never its original intent to overly rely on the same northern neighbor that had spent decades trying to subvert it with communist insurgents.

The contemporaneous model of China’s early forays into international development, whereby Beijing would ship or promote the migration of a large amount of its culturally insensitive workers to the country in question, inadvertently resulted in tense relations between the new arrivals and the locals. Without realizing it, while China scored positive inroads on the state-to-state level, it was simultaneously weakening its soft power foundation in Myanmar and undermining bilateral trust on the plane of civil society. The US would then adroitly manipulate these resultant sentiments into “Sino-suspicion”, if not outright Sinophobia, as a means of scaring Myanmar away from China and preconditioning its national psyche into considering a possible break with its partner. The closer that Myanmar was forced into working with China as a result of the new Western sanctions, the more strategically dependent it became on it, but occurring concurrently with a fierce anti-Chinese information campaign and Beijing’s own bumbling missteps inside the country, it made many in Myanmar resent what otherwise should have been seen as a privileged and highly respected ally to have.

The Deal And Its Shortcomings:

When it was appropriately identified that the asymmetrical destabilization operations (Saffron Revolution, anti-Chinese psyop campaign, and sanctions) had met their desired objectives, and in anticipation of the forthcoming and years-long-planned Pivot to Asia, the US discreetly approached the Myanmar authorities to offer them what many of their people had been artificially made to want, which was a strategic alternative to China and a lifting of the sanctions regime against their country. While dangling the carrot of these lusted-after perks, the US also held out the stick of another Saffron Revolution in order to pressure Myanmar into acceding to what basically amounts to a “deal that they can’t refuse’. The only thing that the Myanmar generals would have to do for them and their country to reap the perceived benefits is “democratize” through the two-step process of releasing Suu Kyi from house arrest and holding elections that they promised to recognize and abide by. In effect, this would lead to the Color Revolution leader ascending to the height of power and allowing the US and its allies to control the country by proxy.

As an insurance policy against being completely removed from their privileged positions in the slow-motion “democratic” regime change that they agreed to carry out against themselves, the military inserted an important clause into the 2008 Constitution that guaranteed them automatic control over 25% of both chambers of parliament and thereby empowering it with de-facto veto rights over any ‘reforms’ that the forthcoming government chooses to enact. Still, such a defensive strategy is inherently unstable. The veto privileges enshrined in the constitution are such that over 75% of both legislative houses must agree to any proposed constitutional changes, meaning that if a single military representative from both chambers defects to the Color Revolutionaries and the non-military politicians vote unanimously for whatever the given amendment may be, then two individuals could dangerously undermine the entire system.

More than likely, however, it doesn’t seem foreseeable that a unified non-military bloc could be created anytime soon, especially since some of the various parties and people in power are favorable towards the military. Still, the point being made is that a strategic number of military defections alongside skilled politicking at the legislative level are all that’s needed in order to ‘legally’ change the constitution in Myanmar and roll back the armed forces’ influence over the country, thus increasing the likelihood that the US could engage in personally directed operations (bribery and/or blackmail) against strategically positioned politicians in order to bring this scenario about. One of the ways in which intelligence agencies could combine bribery and blackmail in controlling Myanmar’s top military brass is through granting influential power makers lucrative contracts in the post-sanctions environment and then holding out the threat that the economic restrictions could be re-imposed on a personal level if they don’t comply with whatever political action is asked of them.

It appears as though a test run of this strategy was applied against pro-military businessman Steven Law right before the country’s historic elections. In early November 2015, it was reported that the US ‘circumstantially’ found out that the port through which half of Myanmar’s trade flows just so happens to be owned by someone who has a set of personal sanctions enacted against him, raising the prospects that the enforcement of US law “could amount to a de facto trade embargo” against the country. Mysteriously, Reuters did not follow up on this story afterwards, but incidentally the military did not object to the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) historic win and have been faithfully abiding by their pledge to proceed with a ‘democratic transition’, prompting questions as to whether the threat of enforcing sanctions against this singular individual and endangering the vast moneyed military class that he associates with was enough to bring Myanmar’s armed forces to heel. It conceivably appears to be the case, and this template will certainly continue to be applied as needed on a case-by-case basis to enact further political concessions from the country’s military establishment in entrenching unipolarity’s growing influence in Myanmar.

The Pivot to Asia

Grand Strategy:

The US is seeking to employ a three-pronged policy of personal enrichment, domestic rearrangement, and international benefits as a means of enhancing the viability of its Pivot to Asia and tightening its control over Myanmar. The overall purpose that each of these measures are supposed to achieve is to take Myanmar on a diametrically opposite course of development than the one it had previously embarked on alongside China, widening the strategic differences between the two and creating complications for China’s One Belt One Road (New Silk Road) policy of multipolar engagement:

Personal Enrichment

While the US didn’t officially announce its Pivot to Asia policy until October 2011, it obviously had been planning it for years, as topically evidenced by the backchannel diplomatic outreaches that it engaged in with Myanmar prior to its “democratization”. The ruling generals were promised personal enrichment via payments that would be laundered through post-sanctions “contracts” with Western companies, and the people that they represent would have an opportunity to entrepreneurially jump in on the bonanza if they were able to. As quickly as the US opened up the gate to riches, however, it can also just as quickly shut it down when needed, strategically threatening to do so in order to increase its leverage over the country’s key players.

Domestic Rearrangement

The cornerstone of Suu Kyi’s domestic policy and anticipated leadership legacy is expected to be her efforts to end Myanmar’s civil war by implementing an Identity Federalist ‘solution’. While the military may oppose this on principle and has spent over the past 60 years fighting tooth and nail to avoid this scenario, they may be unable or unwilling (whether on their own regard or due to the US’ ‘personal enrichment’ influence over them) to do anything about it. If each of the country’s ethno-regional components acquire a broad degree of quasi-independent ‘self-rule’ (which is what Suu Kyi is likely to advocate as a ‘compromise’ to all parties), then they’ll become political-economic springboards for the US and its allies as they strive to carry their influence closer to China’s borders.

International Benefits

On the international level, Myanmar’s military and moneyed elite (basically one and the same in many ways) were promised investment from their fellow ASEAN counterparts in exchange for “behaving” and not disrupting the “democratic” process of slow-motion, ‘legally’ institutionalized regime change. Included in this package of benefits are India’s Trilateral Highway to Thailand and its Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Program to the “Seven Sisters”, Japan’s East-West and Southern Corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion, and potentially even the US’ TPP restrictive trading arrangement. New Delhi and Tokyo’s projects are designed to make the country an indispensable part of the China Containment Coalition’s non-Beijing vision of mainland ASEAN development, while the TPP would institutionally lock Myanmar into an unbalanced trading relationship with the US and prevent it from ever fully actualizing its natural economic potential with China.

The Trade-Off:

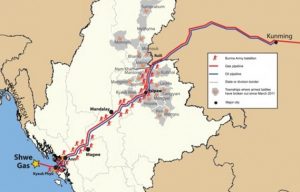

In exchange for the promised benefits that the US is holding out before the Myanmar elite, it required from them that they first cancel two major infrastructure projects with their Chinese strategic partner and thus purposely make Beijing disproportionately dependent on the only important one that remains. Myanmar made its first large step in this direction when it indefinitely suspended the Mysitone Dam in fall 2011, and it took its second one in summer 2014 when it cancelled the $20 billion railroad that was supposed to run between the Yunnan capital of Kunming and the Indian Ocean deep sea port of Kyaukpyu.

The only one of the three large-scale projects that’s left is the China-Myanmar Energy Corridor between these two very same cities, which opened up in January 2015 and carries both oil and natural gas.

The only one of the three large-scale projects that’s left is the China-Myanmar Energy Corridor between these two very same cities, which opened up in January 2015 and carries both oil and natural gas.

Interestingly, it was reported by The Diplomat in January 2016 that China secured a contract to develop the deep water port in Kyaukpyu, which could of course have the dual purpose not only of accommodating large LNG vessels, but also super large “Panamax” ships for commercial shipping use. The latter is very important because it could signify that China hasn’t completely abandoned its hopes to one day build a high-speed railroad between the two energy-linked cities and thereby diversify the China-Myanmar (Energy) Corridor with the full-spectrum connectivity that it was originally intended for.

Beijing’s Pushback:

The US’ Pivot to Asia is conditioned on encircling China and strategically cutting it off from non-unipolar-controlled access routes to the global economy. Beijing’s response is all of this is to push back in the most creative ways possible, expertly deflecting the detrimental geopolitical conditions that Washington is trying to create for it and cleverly turning them around to its own advantage if it can’t outright reverse them in full.

For example, if China’s dwindling influence on the Myanmar establishment isn’t sufficient enough to prevent the Identity Federalization of the country, then it could proactively reverse its established policies and seek to ingratiate itself with the Kachin- and Shan-based rebels in order to preempt their future federalized entities from being co-opted by the US and its allies, thereby establishing a measure of strategic depth to insulate the People’s Republic from any Hybrid War destabilizations that the US tries to engineer afterwards. If anything, China might even one day be in a secure enough position to use its influence over these Identity Federalized areas as a complementary component to its state-to-state diplomacy in promoting its policies in Myanmar.

Likewise, if Suu Kyi ends up becoming the political kingmaker in Myanmar and is able to successfully wrest tangible control over most or all of its affairs from the military (again, in coordination with the US’ ‘personal enrichment’ strategy against the armed forces), then it doesn’t necessarily mean that all is lost for China. Building off of the unprecedented outreach that it extended to her while she was still an “opposition” candidate, Beijing could theoretically succeed in ‘wining and dining’ her to the point where ‘The Lady’ agrees to reestablish the Kunming-Kyaukpyu Railroad and revitalize the China-Myanmar Strategic Corridor (the Myanmar Silk Road).

Contingency Measures

The US intends to further its grand strategic plans for Myanmar via the personal diplomacy that it practices with the country’s military elite and Suu Kyi, but the success of its ultimate ambitious is far from assured. As was just argued above, China has the possibility of turning the US’ own plans against it and trapping it strategists in an unexpected dilemma of their own making. The US has invested way too much political capital in Suu Kyi to ever publicly betray her, and the Myanmar Color Revolution icon already enjoys firmly established support among the Western public. Should she switch sides and ally herself with the Chinese for whatever self-interested reason she may have, the US would be unable to credibly reverse the decades-long narrative that it so carefully crafted about her being a ‘pro-democracy goddess’, and although it could still deploy a Color Revolution against her, such a regime change tactic wouldn’t have any ‘normative’ support among the domestic or international audiences.

Instead, the most plausible way that the US could destabilize a pro-China Suu Kyi government is through manipulating the country’s civil war factions against one another and her. It would need to take care in ensuring that this is contained as much as possible to the Kachin and Shan states that border China (and the latter being the area through which the China-Myanmar Energy Corridor runs) so as not to unnecessarily jeopardize its Indian and Japanese allies’ transnational infrastructure projects in the country. If the strategic need arises, though, then the US would likely be willing to see the renewed civil war’s area of operations expand and endanger its partners’ projects so long as this increased the odds that it would also sabotage China’s.

An escalation of ethno-regional violence (no matter whether it’s contained to Kachin and Shan states or not) and the highly publicized failure of her legacy-making efforts to bring peace to the country could tarnish her reputation among the people and lead to a measureable decline of support for her leadership both at home and abroad. Additionally, if her government found itself depending on the same military that she had railed against for decades in order to restore stability to the periphery and/or chastise rebel groups that refuse to abide by a future peace treaty, then it could damage her image by making her appear to be “just another politician” that “sold out” her principles and simply did and said whatever was necessary in order to get into power.

It doesn’t matter if this is actually the case or not – the importance lies in how it’s represented via media and NGO platforms and the effect that this has on the domestic and international public’s perception of her. If it makes headway in conditioning the people that Suu Kyi might not be “administratively qualified” to de-facto lead the country despite her “democratic credentials”, then the US could much more easily go forth with an in-party coup or enact a corresponding Color Revolution to reverse-engineer yet another regime change Hybrid War in Myanmar against her and/or her presidential proxy. The key to understanding how this interconnected strategy could work is for one to become acquainted with the complexities of the country’s civil war, which brings the research along to its next section before concluding with the actual Hybrid War scenarios that could be summoned.

Andrew Korybko is the author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar (I) | Oriental Review

Pingback: The Rohingya Crisis: Conflict Scenarios And Reconciliation Proposals | OrientalReview.org

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar (I) | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: As consequências estratégicas do estado de emergência em Mianmar - Jornal Puro Sangue