Italy and the Balkans

After the unification of Italy from 1859 to 1866,[i] the Italian administration accepted the foreign policy of the creation of a greater Italian state which should resemble a certain extent on the ancient Roman Empire.[ii] The project of a “New Roman Empire” was directed toward the Italian direct control or territorial acquisitions of the parts of the Mediterranean Sea, the Adriatic Sea, the Tyrrhenian Sea, and certain territories in North Africa and Asia Minor. However, for the very reason that the Italian attempt to conquer African Ethiopia in the years of 1886−1896 failed, the Italian pivotal aim of the foreign policy after the Ethiopian War was directed toward the Balkans.[iii]

However, there were two most important focal points of the Italian interest in the region of South-East Europe: 1) Albania, and 2) East Adriatic littoral. The press in Italy at the turn of the 20th century (around 1900) called openly the whole Adriatic Sea as the Italian Mare Nostrum (Our Sea). To be a master of the Adriatic Sea became the principal precondition for the Italian economic and political infiltration into the Balkan Peninsula. Special importance for the Italian Balkan policy was Albania and the Albanian populated Balkan lands for the very reason that the main direction of the Italian penetration into South-East Europe was seen to be via Valona, Elbasan, and Bitola with the final destination at the Bay of Thessaloniki. The Italians verily followed, in this case, the ancient Roman military road Via Egnatia, which connected Italy with the East (with Byzant/Constantinople and further with Asia Minor).[iv] By contrast, the Austro-Hungarians followed in their penetration into the Balkans different but also the ancient Roman military road – Via Militaris, from Belgrade (Singidunum) via Sofia (Serdica), Plovdiv (Philippopolis), and Edirne (Adrianopolis) to Istanbul (Constantinople).[v]

The Italian project of the Trans-Balkan Railway-Line is the best illustration of the Italian Balkan plans and way of economic-political infiltration into South-East Europe’s hinterland. Rome, in order to be more active in the Balkan affairs, required in 1902−1904 that the Italian police forces would implement necessary reforms in the Ottoman Bitola (Monastir) Vilayet.[vi] In the year 1911, when the 1911−1912 Italo-Ottoman War started,[vii] the Italian trade and financial capital already prevailed over the Austrian-Hungarian one in the area of Albania’s littoral of both the Ionic and the Adriatic Sea. What regards the whole territory of the Ottoman Albania, as the focal Italian point of colonial expansion in South-East Europe, in the years of the 1912−1913 Balkan Wars the presence of the Italian capital in the country reached the second place, just behind the Austrian-Hungarian one. The Italian trade companies mastered around 25% of the export-import trade from Scutari and 30% from South Albania. The total financial operations in the cities of Valona and Durazzo (Durrës) were done by the Italian banks but primarily by the Society for the Trade with the East.

The Italian project of the Trans-Balkan Railway-Line is the best illustration of the Italian Balkan plans and way of economic-political infiltration into South-East Europe’s hinterland. Rome, in order to be more active in the Balkan affairs, required in 1902−1904 that the Italian police forces would implement necessary reforms in the Ottoman Bitola (Monastir) Vilayet.[vi] In the year 1911, when the 1911−1912 Italo-Ottoman War started,[vii] the Italian trade and financial capital already prevailed over the Austrian-Hungarian one in the area of Albania’s littoral of both the Ionic and the Adriatic Sea. What regards the whole territory of the Ottoman Albania, as the focal Italian point of colonial expansion in South-East Europe, in the years of the 1912−1913 Balkan Wars the presence of the Italian capital in the country reached the second place, just behind the Austrian-Hungarian one. The Italian trade companies mastered around 25% of the export-import trade from Scutari and 30% from South Albania. The total financial operations in the cities of Valona and Durazzo (Durrës) were done by the Italian banks but primarily by the Society for the Trade with the East.

With the marriage of the Italian hear of the throne, Vittorio Emanuel Orlando, with the Montenegrin Princess Helen (Jelena), a daughter of the Montenegrin Prince Nikola I, in 1896 the door to Montenegro was open for the Italian capital and political influence. Up to 1912, the Italian capital was predominant in Montenegro’s economy. For instance, the concession to construct the first Montenegrin railway-line (Bar-Virpazar) was given to the Banca Comerciale Italiana. The same bank started to exploit the steamboat traffic at the Lake of Scutari.[viii]

The Italian intention to use Albania’s territory as the bridge for its penetration into South-East Europe, as well as to transform the Strait of Otranto into the Italian Gibraltar, followed by Rome’s wish to annex Alto Adige (Süd Tyrol), Istria, and Dalmatia led Italy to the open clash with Vienna-Budapest upon the lordship over the Adriatic Sea and the Balkan hinterland.[ix] At that time, the Austro-Hungarian belligerent military and political circles created a motto: “Our future is in the Balkans, our stumbling block is Italy”. In order to dismiss the main obstacle for the Austrian-Hungarian predominance in the Balkan affairs, a Chief of the Austrian-Hungarian General Headquarters Conrad von Hötzendorf advised the Emperor “firstly to settle the affairs with Italy”.[x] Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a hearing of the Austro-Hungarian throne, predicted in February 1913 in his conversation with Conrad von Hötzendorf that “our principal enemy is Italy and against Italy, we had to fight one day in order to regain Venice and Lombardy”[xi] (lost during the wars for the Italian unification).

For the Italian Balkan policy, the most dangerous Austrian-Hungarian plan with regard to the region of South-East Europe was a design of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary to transform present-day North Albania into the Austrian-Hungarian foothill for the further advance towards the Balkan hinterland. For that reason, Italy made serious efforts to thwart the Austro-Hungarian intention to master the east-central portion of the Balkans, including the areas populated by the Albanian majority or minority as Albania proper, Kosovo-Metochia, East Montenegro, and West Macedonia. In other word, to keep Vienna-Budapest as far as from the Strait of Otranto became a crucial goal of the Italian policy in the Balkans around 1900. An additional problem for Italy was Serbia’s territorial pretension on present-day North Albania as well as the Greek wish to dominate over North Epirus (present-day South Albania).[xii]

In order to obviate the Serbian-Greek division of Albania, Italy in principle did not support the creation of the Balkan League against the Ottoman Empire since the league would make stronger both Serbia and Greece. Rome showed its real attitude toward the Balkan League[xiii] when Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, and Bulgaria proclaimed the war against the Ottoman Empire in October 1912 as Italy at the same moment put an end its military operations against the Ottoman Empire in Lybia in order to make better Ottoman military position at the Balkans against the members of the Balkan League.[xiv] The Italian newspapers at that time were writing that “the Slavdom is coming via Montenegro to the Adriatic”; the Slavdom which was “just behind Albania” and in the following years and decades the Slavdom will require Bosnia-Herzegovina, Trieste, Istria, and Dalmatia.[xv] The Italian diplomatic representative in Vienna even tried to convince the Austrian-Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs that for the sake of the Italian geopolitical[xvi] and economic interests in the region, Serbia was more dangerous than the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[xvii] Consequently, regardless of the whole spectrum of the Italian disputes with Austria-Hungary on supremacy over South-East Europe, the disintegration of the Balkan League was their joint interest. Their common goal was “to prevent Slavic domination over the Adriatic Sea”.[xviii]

Surely, the question of the division of the spheres of influence over the region of South-East Europe between the European Great Powers including Italy as well as was one of the focal causes of friction which threatened to upset the peace of Europe at the turn of the 20th century as they were:

- A naval rivalry between the United Kingdom and the German Empire.

- The French intention to return lost Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871 (as a consequence of the 1870‒1871 Franco-Prussian War).

- The German Empire accused the Triple Entente to “encircle” it but, in essence, the Germans have been very disappointed with the results of their imperialistic (Weltpolitik) policies after the German unification in 1871 as their overseas colonial empire was small in comparison with those of other European Great Powers – the same expansionistic syndrome that Italy had after its own political unification in the 1860s.

- Russia was suspicious of the ambitions by the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary in South-East Europe and worried about the growing military and economic power of the German Empire.

- The Serbian nationalistic patriotism based on the desire to liberate the Serb nation from control by other states, i.e., the Ottoman Empire and the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary and, subsequently, to establish a Greater Serbia as a national state of all Serbs.

- The Austro-Hungarian desire to launch a “preventive war” to destroy and occupy the small Kingdom of Serbia before she became strong enough to provoke the breakup of the Dual Monarchy and, therefore, to resent the transformation of Serbia into the Russian client state.[xix]

- The Italian desire to get more overseas colonies and territories on the eastern littoral of the Adriatic Sea. In another word, the nations that have been historically divided, such as the Germans and the Italians, could only join in the imperial game when they had come together and formed a single military and financial political unit, i.e., the nation-state. And as soon as did it their first act on the international arena was to try to acquire overseas territories, i.e., colonies. But they were among the most brutal of the imperialists as they have been late in comparison to the others.[xx]

- The desire by the Triple Entente to keep the pre-war status quo in international relations.

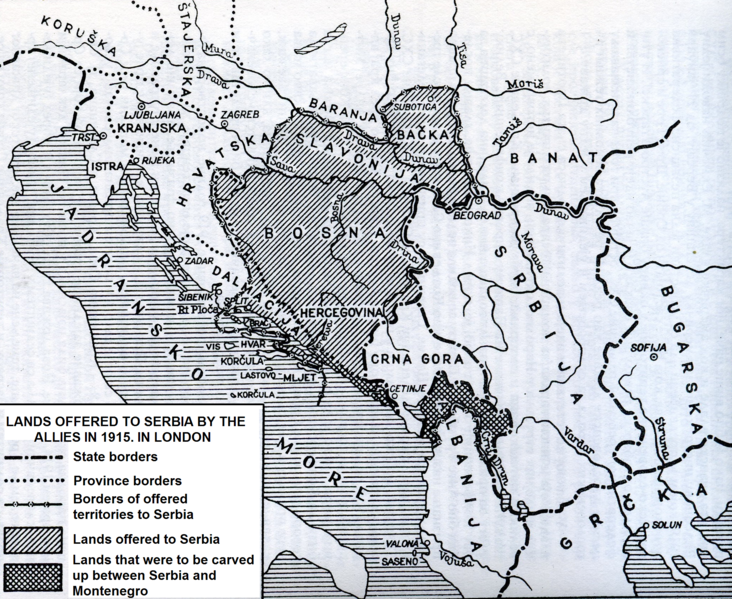

Arising from all these resentments and tensions abovementioned came a series of political events which culminated in the outbreak of the Great War in the summer of 1914 in which Italy took active military participation from May 1915.[xxi] In the Great War, Italy was hoping to get the Italian-speaking provinces of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary followed by the territories along the eastern littoral of the Adriatic Sea. In order to realize its own war aims, Italy signed in April 1915 a secret London Treaty with the Cordiale Entente according to which, France, the United Kingdom, and the Russian Empire promised Italy Trentino, South Tyrol, Trieste, part of Dalmatia, Istria, Adalia, some islands in the Aegean Sea (the Dodecanese with Rhodes), and finally a protectorate over Albania. The member-states of Cordiale Entente hoped that by keeping part of the Austro-Hungarian troops occupied at the Italian front, the Italians would relieve pressure on the Russians that would have positive effects for France and the United Kingdom on the Western Front. However, in the practice, the Italian army fighting in the Alps against the soldiers of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary made little headway and their efforts were to no avail. As a consequence, the Russians were unable to progress at the Eastern Front against Austria-Hungary and Germany.

Reposts are welcomed with the reference to ORIENTAL REVIEW.

Endnotes:

[i] On the unification of Italy, see in [Darby G., The Unification of Italy, Second Edition, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013]. The unification of Italy was a long and complex effort against the Habsburg occupiers, local Italian monarchs with the medieval origins (for instance, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies or the Duchy of Modena), and against the Vatican conservatism. The idea of unification was driven by a sense that Italy needed a modern, united democratic state in order to pull her into the modern Western world [Marr A., A History of the World, London: Macmillan, 2012, 404]. Italy was historically marked by fundamental regional divisions, tensions, conflicts, and wars. The political and economic tensions survived and after the unification in the 1960s now between the southern and the northern regions of Italy. North Italy, especially Lombardy, experienced strong industrialization after the unification which led this part of Italy to be the leading and wealthiest areas of the country and one of the wealthiest regions in Europe at the end of the last century. However, by contrast, South Italy was dominated by a share-cropping system that kept the majority of the population as landless workers who have been employed by a tiny number of large landowners. One of the central elements in the Italian politics from the unification to the conclusion of the Lateran Treaties in 1929 was the relationship between the secular authorities on one hand and the Roman Catholic Church (Vatican) on another. After the unification of Italy, in which the Vatican lost its own state and huge territories, the Pope forbade until 1918 all Roman Catholics to participate in the functioning of a new liberal Italian secular state [Palmowski J., A Dictionary of Twentieth-Century World History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, 302‒303]. In essence, the Italians ultimately could not build Italianess identity based on the Roman Catholicism for the very reason that the Pope and Vatican were very hostile to the Italian national movement (Risorgimento). The fractured nature of the Italian society, the strong linguistic diversity and regionalist identities followed by massive social conflict, and a poor education system participated as the factors which made the Italian nation a rather volatile and problematic project to be realized even up today [Berger S., (ed.), A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Europe 1789‒1914, Malden, MA‒Oxford, UK‒Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006, 179].

[ii] On the history of Ancient Rome, see in [Zoch A. P., Ancient Rome: An Introductory History, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998; Gibbon E., The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, London: Penguin Books, 2001: Beard M., SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015; Baker S., Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire, London: BBC Books, 2007].

[iii] On the issue of the Italian colonialism and imperialism after the unification in 1861/1866, see in [Negash T., Italian Colonialism in Eritrea, 1882−1941: Policies, Praxis, and Impact, Coronet Books Inc, 1987; Ben-Ghiat R., Fuller M. (eds.), Italian Colonialism, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005; Duncan D, Andall J., Italian Colonialism: Legacy and Memory, Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2005; Andall J., Duncan D., (eds.), Italian Colonialism: Legacy and Memory, Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2005; Finaldi M. G., Italian National Identity in the Scramble for Africa: Italy’s African Wars in the Era of National-Building, 1870−1900, Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2009; Finaldi M. G., A History of Italian Colonialism, 1860−1907: Europe’s Last Empire, London−New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2017].

[iv] O’Sullivan F., The Egnatian Way, Stackpole Books, 1972.

[v] See the map in [Motta G. (Direzione cartografica), Atlante Storico, Novara, Instituto Geografico de Agostini, 1979, 28]. The another project of the railway-line in the Balkans was the Adriatic railway-road favored by Serbia but not supported either by Austria-Hungary or Italy and Bulgaria [Ратковић Б., Ђуришић М., Скоко С., Србија и Црна Гора у Балканским ратовима 1912−1913, Друго издање, Београд: БИГЗ, 1972, 19, Ћоровић В., Односи између Србије и Аустро-Угарске у XX веку, Београд: Библиотека града Београда, 1992, 108−141].

[vi] Архив Министарства иностраних дела, Београд, Извештај из Рима, 14. мај 1903, п. бр. 46; Архив Министарства иностраних дела, Извештај из Скопља, 16. XII, 1904; Архив Министарства иностраних дела, Извештај из Рима, п. бр. 31, 101; Documenti diplomatici, Macedonia, Roma, 1906, 151−179, 280−292; Pavolni J. V., Le problème macédonien et sa solution, Paris, 1903, 42−45; British documents on the Origins of the War, 1899−1914, Vol. V, 71.

[vii] Beehler H. W. C., The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911 to October 18th, 1912, Annapolis, MD, 1913.

[viii] Ђуришић М., Први балкански рат 1912−1913, том III, Београд, 8−9; Јовановић Ј. М., “На двору црногорском, поводом успомена барона Гизла”, Записи, бр. II/1, 10−13; Ракочевић Н., Политички односи Црне Горе и Србије 1903−1918, Цетиње, 1918.

[ix] About the concept of irredentism and its role in European politics, see in [Kornprobst M., Irredentism in European Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008].

[x] Pribram A. F., Die politischen Geheimverträge Österreich–Ungarns 1879−1914, ester Band Wien, 1920, 267−268; Feldmarschall Conrad, Aus meiner Dienstzeit 1906−1918, Vol. III, Leipzig−München, 1922, 171.

[xi] Дедијер В., Сарајево 1914, Београд, 1966, 245; Дипломатски архив, Пресбиро, Београд, италијанска штампа, јун 1913.

[xii] The territory of North Epirus was a part of the project of a Great Idea – the creation of a unified national state of the Greeks. About nation building and the project of Great Idea, see in [Clogg R., A Concise History of Greece, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992, 47−99]. However, the Albanians as well as pretended on North Epirus as their ethnographic region that was for the first time clearly expressed by the First Prizren League in June 1878 when for the first time in the Albanian history the project of a Greater Albania was proclaimed [Бартл П., Албанци од Средњег века до данас, Београд: CLIO, 2001, 94−102].

[xiii] The Balkan League was formed in March 1912 when Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro signed bilateral agreements. Their first demand was far-reaching reforms for those territories still under the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and then, when these were not met, declared war [Pagden A., World at War: The 2,500-Year Struggle Between East and West, Oxford‒New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, 390].

[xiv] Nevertheless, during the 1911‒1912 Italian-Ottoman War, Italy conquered north Tripoli and later by 1914 had occupied much of Libya, declaring it as an integral part of the country in 1939 [Isaacs A. et al. (eds.), Oxford Dictionary of World History, Oxford‒New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, 317].

[xv] Tribuna, June 1913.

[xvi] On geopolitics, see in [Dodds K., Global Geopolitics: A Critical Introduction, Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2005].

[xvii] Готлиб В. В., Тайная дипломатия во время первой мировой войны, Москва, 1960, 214.

[xviii] Pribram A. F., Die politischen Geheimverträge Österreich–Ungarns 1879−1914, Wien−Leipzig, 1920, 292−293.

[xix] Lowe N., Mastering Modern World History, Fourth Edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, 5‒7.

[xx] Marr A., A History of the World, London: Macmillan, 2012, 439. About the colonial expansion of West European states, see in [Del Testa W. D. et al. (ed.), Global History. Cultural Encounters from Antiquity to the Present: The Age of Discovery and Colonial Expansion 1400s to 1900s, Volume Three, New York: Sharpe Reference, 2004]. On the colonial terror and genocide, see in [Naimark M. N., Genocide: A World History, Oxford‒New York, Oxford University Press, 2017, 34‒85].

[xxi] On the Great War, see in [Hernández J., Pirmasis pasaulinis karas, Kaunas: Obuolys, 2011].

Comments