On 1 June 2019, Beijing introduced higher tariffs on around $60 billion worth of US products. This was in response to a decision by the US government on 10 May 2019 to increase tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods from 10 per cent to 25 per cent. Later, US President Donald Trump ordered tariffs to be imposed on a further $300 billion worth of Chinese goods. Washington has actually been waging a trade war against Beijing for some time now and is using the technology sector to bully the country in the hope that it will undermine its economic position as the US once managed to do with Tokyo.

The US–China trade war is like the remake of an old TV show. The first series was dedicated to the “economic Pearl Harbor” of the 1980s, when Japanese companies flooded America with their cars and electronics. Having risen from the nuclear ashes, Japan had the strongest trade balance and Japanese companies accounted for 40 per cent of global capitalisation. It is unsurprising that the US establishment saw the “Japanese economic miracle” as a greater threat to US security than Soviet nuclear missiles. As a result, the US undermined the Japanese economy and forced Tokyo into a “liquidity trap”.

Last year, the US launched a new series of the TV show, but this time with China in the lead role. The Asian drama, which began in 2018 with the US increasing the tariff on Chinese solar panels to 30 per cent, is now in its second year. And it seems that the US is reckoning on a few more series yet.

Economic hara-kiri

In many respects, the Chinese economy is repeating Japan’s success in the 1980s. At that time, Japan was at the peak of its economic power. While Japanese exports were around the $4.1 billion-a-year mark in 1960, this had increased to $287 billion a year by 1990. The country exported cars, car parts, office equipment and other electronics around the world.

In those days, Japanese exports to the US far exceeded US exports the other way. In 1982 alone, the trade deficit between the two countries grew from $15 billion to $36.8 billion. In 1981, for example, the US imported 1.8 million cars from Japan, but the Japanese only imported around 4,000 from the US. In addition, Japan began to be perceived as a world leader that far outstripped the US technologically.

As a junior ally of the US, Japan was able to successfully develop its economy until it became a threat to its patron. The American elite were gripped by a paranoid fear that the US would be destroyed by cheap Japanese exports in a competitive war. To reduce its trade balance deficit, the US imposed the Plaza Accord on Japan in 1985, which gradually paralysed the Bank of Japan. Under the terms of the accord, Tokyo had to revalue the yen against the dollar. So, in the years that followed, the value of the yen was no longer determined in Japan, but in the US.

As a junior ally of the US, Japan was able to successfully develop its economy until it became a threat to its patron. The American elite were gripped by a paranoid fear that the US would be destroyed by cheap Japanese exports in a competitive war. To reduce its trade balance deficit, the US imposed the Plaza Accord on Japan in 1985, which gradually paralysed the Bank of Japan. Under the terms of the accord, Tokyo had to revalue the yen against the dollar. So, in the years that followed, the value of the yen was no longer determined in Japan, but in the US.

In just three years, the rate of the yen almost doubled, from 265 to 138 yen per dollar, and Japanese exports were no longer as cheap as before. In an effort to compensate for the negative effect of the worsening trade balance, Tokyo decided to increase investment and lending and lower interest rates (from 5 per cent in 1985 to 2.25 per cent in 1989). Japanese stock prices began to rise steadily, inflating the credit bubble.

The very best US experts declared as one that the high stock prices were due to the unique nature of Tokyo’s economy. They were so convincing, in fact, that even the Japanese themselves ended up believing in the uniqueness of their economy. From 1988, Japan began to actively build factories and expand production. It took a while for the realisation to sink in that there wouldn’t be a demand for such production volumes on the world market. As a result, it all ended with the collapse of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1990, which plunged Japan into years of deflation. For Tokyo, the 1990s became the “lost decade”.

An indomitable rival

Having learned from Japan’s ordeal, China doesn’t trust the West’s advice and is flatly refusing to open its own financial market. Beijing also has a number of advantages that we Russians believe will prevent the country from repeating Japan’s unfortunate experience.

First, the yuan is not as integrated into the global financial system as the yen had been. China is not bound by any international financial obligations as Japan had been with the Plaza Accord, so Beijing is less dependent on Washington and can negotiate on an equal footing, as well as take independent steps.

Second, China has an enormous domestic market with one and a half billion consumers. Despite America’s tangible impact, the market is coping well with the pressure. The Chinese government is placing great emphasis on developing domestic demand and consumption in order to build a “moderately prosperous society” by 2021.

Third, the Chinese economy itself is considerably stronger than the Japanese economy had been at the peak of its development. If we compare the volume of Japanese exports in 1982 with China’s exports in 2016 in real prices (base year – 1970), it works out as $63.3 billion and $1.186 billion respectively. China is also banking on cutting-edge technologies. Today, China’s top exports are expensive high-tech products: broadcasting equipment, computers, office equipment, integrated circuits and telephones.

A delayed denouement

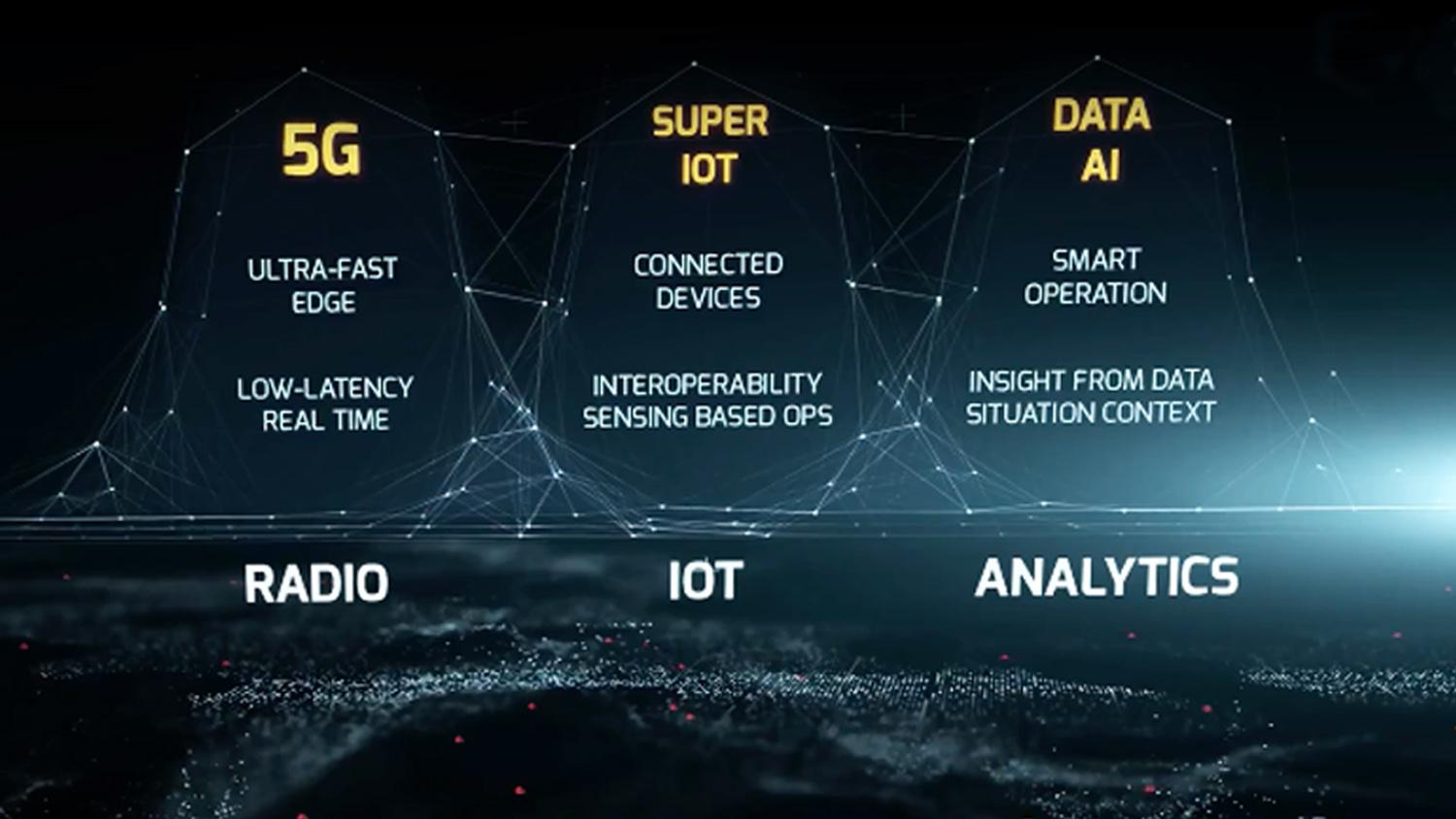

The main battle between the US and China today is for the position of global technology leader. It is believed that the victor on this front will be whichever country provides the best conditions for developing such advanced industries as artificial intelligence and 5G. And these are exactly the Chinese industries that the US is trying to damage by raising tariffs on high-tech Chinese goods and putting Chinese companies on blacklists.

Huawei, for example, has been under constant pressure for a few months now. The US is driving the company out of its own market and disrupting its work in other countries by preventing it from purchasing components. America’s fears are well founded. Huawei invests huge sums of money in China’s technological future: up to 10 per cent of its profits (more than $13 billion) are spent on new developments that employ around 80,000 people.

Huawei’s current position is far from fatal, however. The company received just 7 per cent of its revenue from the US market, but if China retaliates then Apple could lose as much as 20 per cent of its revenue. Huawei will also be able to get the components it needs on the Taiwanese market, and global demand for its services remains high. Incidentally, at The Future of Asia conference that took place on 30 May 2019 in Tokyo, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Bin Mohamad explained that his country would continue cooperating with Huawei precisely because the company’s technologies are so far ahead of anything else.

About time the USA Bully had its Wings clipped.

excellent analysis this is the true