Additional factors on the creation of common pan-European identity

The above-presented views address possible concepts that can be applied in the practice in order to establish common pan-European identity, yet it is probably difficult to choose one view over another without encompassing a kind of mixture from all of them. The existing views also neglect very important issues of additional factors that could play a crucial role in the emergence of common pan-European identity. The next paragraphs address these additional factors.

At the heart of the creation of a strong common pan-European identity is the fact that the borders within the EU have dissipated and the citizens of the EU are able to travel freely without any visa requirements regardless the fact that many of the outsiders (“foreigners”) have to pass a certain, and even very difficult, bureaucratic procedure in order to get the EU’s visa. In the other words, at the same time of lifting the wall-borders between the EU’s Member States, especially of those who signed the Schengen Agreement (June 14th, 1985) followed by the Schengen Convention (1990) which led to creation of the Schengen Area (March 26th, 1995), the EU’s wall-borders with the outside world became even stronger.[i]

Together with the Schengen Area’s policy, there are additionally very successful factors that strongly contribute to the creation of the feeling to be a “European”. For instance, the “Erasmus/Socrates” student and teaching staff exchange (mobility) program (est. 1987) has allowed for 1.2 million Europeans to study abroad within Europe [6][ii] up to 2005. This unique opportunity allows students and teachers to experience life in/of another country, participating in their understanding of a common European identity. The “Erasmus/Socrates” program (“Lifelong Learning Program” from 2007) is just one element for diversification of transcontinental experience and surely a part of the EU’s policy of European integration.[iii]

A lifting of the labor restrictions within the whole EU is a very important additional factor in creating the common European identity and feelings of solidarity as a basis for the further process of (stronger) European integration under the EU’s umbrella. In this respect, for instance, the EU has passed a law after May 2004 requiring from all old Member States (EU-15) to lift their labor restrictions on the EU-8 (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Hungary) by the year 2011. Following this requirement, Sweden, Ireland, and the United Kingdom were the first to lift their labor restrictions. Finland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece are now completely open to the EU-8 as a result of such a policy. In the beginning, Denmark allows EU-8 citizens to stay up to 6 months to search for a job if they find one they are allowed to work legally and to arrange their residence permits. For the citizens of Bulgaria and Romania (accepted in 2007 to the EU), only Sweden and Finland have completely lifted all restrictions from the very beginning, with the other Member States implementing permit schemes. Today, traveling from place to place within the EU and working in different EU’s countries has been made both easier and cheaper.[iv] Budget airlines offer extremely competitive prices to destinations across the continent, while the interconnectivity of bus and rail lines offers easy access throughout Europe often at discounted prices as well. The lack of restrictions and the access to move comfortably has created a new understanding of the European unity and subsequently of common pan-European identity within the EU’s framework.[v]

If a strong common pan-European identity has to emerge, conventional wisdom will tell us that it will certainly begin with the young generations who easily adapt to the change and novelties but as well as the young generations are mostly fitted to ideological and political manipulations and propaganda influences. The possibilities to become the “European” for the youth are numerous, with the open borders within the EU, and strong cultural and educational EU’s exchange programs, such as above mentioned “Erasmus/Socrates”, etc. The fact is that the possibilities for the young Europeans today are vast compared to the past. Technological advancements, like the internet, make cross-cultural communication both easy and effective. All of these facilities are undoubtedly contributing to the process of creation of the common pan-European solidarity and identity but only within the EU’s ideological and geopolitical premises which are in many spheres Russophobic. Moreover, the interconnectivity of the national youth councils protects and aids the voice of youth throughout the EU and beyond. Many complex networks of the youth councils have emerged, including the EU Youth Forum, the Council of Europe, and the European Youth Portal. By protecting the voices of youth today, these networks are paving the way for the (Russophobic) leaders of tomorrow. Throughout the process, the interaction between the national youth councils would help to break down cultural barriers and aid in the process of common pan-European identity formation. As one of the EU’s officials said:

“They [the European youth] are not asked to give up their national or regional identity – they are asked to go beyond it, and that it what pulls them closer together. We are creating a community in which diversity is not a problem but a characteristic. It is an integral part of feeling European” [6][vi]

As the EU becomes more centralized and intercultural communication has become commonplace, an established means of communication has become essential. The English language has become a global phenomenon, serving as an auxiliary language for the citizens across the globe and more importantly throughout whole Europe as a continent. The English language emerged as a world-wide language largely as a legacy of the colonial policy of the British Empire and as well as the evolution of the United States into an economic and political superpower in the 20th century [52] taking the role of a global policeman at the time of the Cold War 2.0. For these reasons, the English language has established itself as a lingua franca in international business and subsequently as a de facto auxiliary language for international communication which can significantly participate in the process of European solidarity and identity creation.[vii] Despite the rise of the English language as an auxiliary and mediator language, the EU still has almost 30 official languages and therefore spends heavily on translational services. In fact, for instance, in 2005 the total amount was “€ 1123 million, which is 1% of the annual general budget of the European Union. Divided by the population of the EU, this comes to € 2.28 per person per year” [15].

However, the EU has no plans of reducing the number of official languages anytime soon and according to the official website of the EU this is justified as follows:

However, the EU has no plans of reducing the number of official languages anytime soon and according to the official website of the EU this is justified as follows:

“In the interests of democracy and transparency, it has opted to maintain the existing system. No Member State government is willing to relinquish its own language, and candidate countries want to have theirs added to the list” [15].

The EU has decided not to switch to one official language (the English?) by now because of at least two reasons:

- “It would cut off most people in the EU from an understanding of what the EU was doing. Whichever language was chosen for such a role, most EU citizens would not understand it well enough to comply with its laws or avail themselves of their rights, or be able to express themselves in it well enough to play any part in EU affairs”.

- “Of the EU languages, English is the most widely known as either the first or second language in the EU: but recent surveys show that still, fewer than half the EU population have any usable knowledge of it” [39].

However, despite the EU’s decision to keep almost 30 official languages, having a common communicator amongst everyday citizens is the essential factor for creating a common identity. Moreover, the English language is often the preferred taught language for foreign students partaking in many different “Erasmus/Socrates” exchange locations. While the EU’s statistics claim that half of the EU’s population has no usable knowledge of the English language, naturally this statistic weighs heavily towards the older population. As addressed in the previous section, the role of the youth in establishing a pan-European identity is (very) probably crucial one. With the English language (or any other) as a lingua franca, the speaking youth brake cultural barriers and this process are going to continue for sure in the future.[viii] The problem, however, can rise with the Brexit as the UK is only EU’s Member State in which the English language is an official.

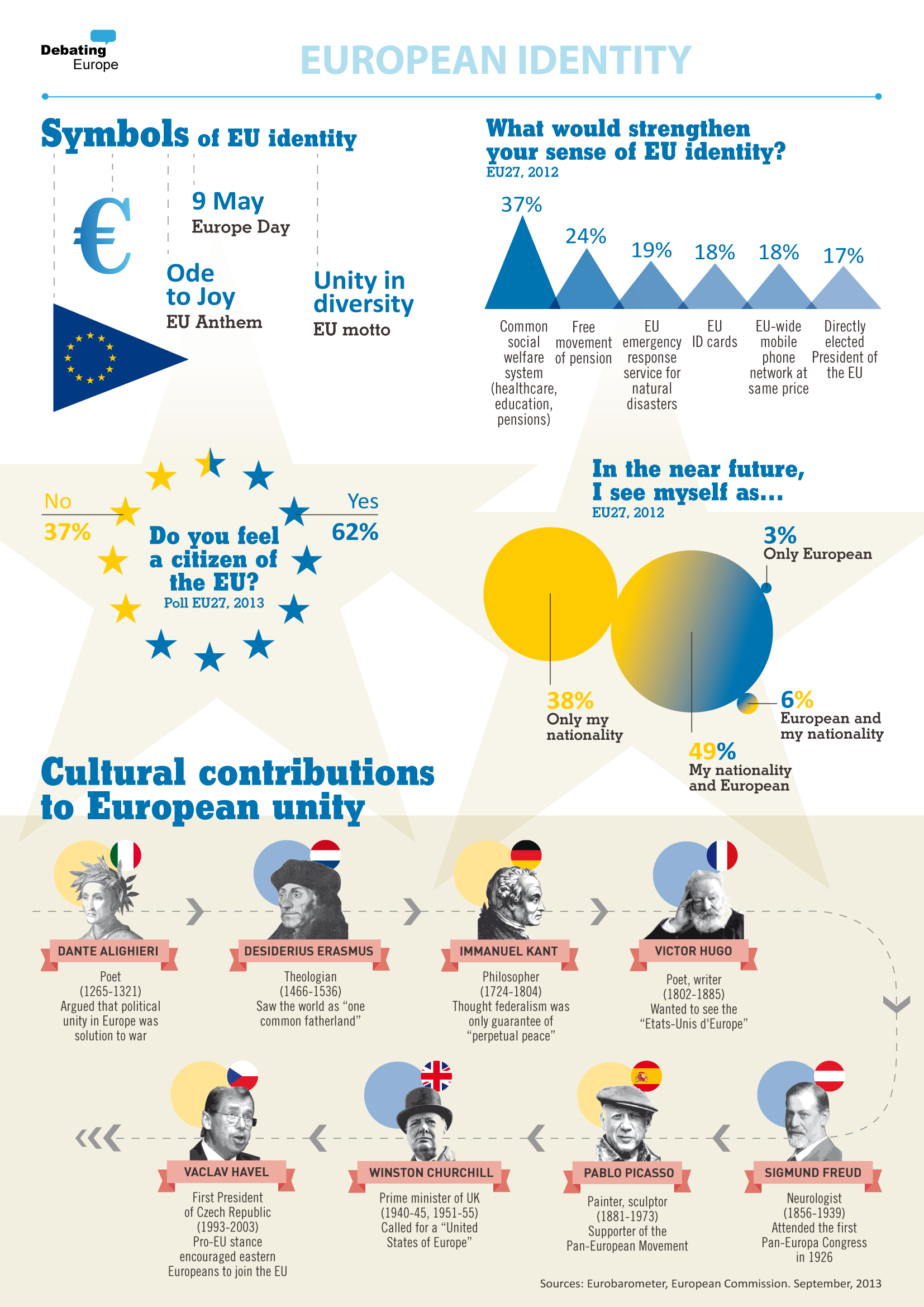

The role of pop-culture supported by transnational mass media is particularly important for the creation of the common European identity as practically it has a decisive effect on it.[ix] In many instances, pop-culture can help to establish a common identity, particularly among the younger generations. For instance, within the music industry, each year the Eurovision Song contest encapsulates the attention of millions of viewers. Regardless of the fact that many experts stress that the context of it is of (very) low quality, there are and those who are seeing the Eurovision Song as a good promoter of the pan-European identity and reciprocity[x] (followed by the promotion of anti-Christian European LGBT’s morality and values).

The development of common European sports teams is also of extreme importance for the creation of common pan-European identity and solidarity. Such steps are already done and are going to be further built-up in the future. For instance, in professional golf, there is a European team that faces an American team in the semi-annual Ryder Cup. There has been a discussion of creating a European Union Olympic team; however, a Eurobarometer survey shows that only 5% of the EU’s citizens claim that this would make them feel more European [41]. Pan-European sports competitions such as football’s (soccer) UEFA Champions League and UEFA Cup or basketball Euro League and Euro Cup can strongly contribute to the creation of the feelings to be European. However, although such competitions might help define common pan-European identity from a pop-culture sense, the events also aid to national pride as fans often take pride in supporting the teams from their country. Thus such events both aid and hurt the establishment of common pan-European identity. Furthermore, international football competitions such as UEFA’s Euro and the FIFA’s World Cup, like similar competitions in basketball and other mass popular sports, put a strong emphasis on national pride as they see individual states competing against one another for pride and glory (aside from enormous financial compensations). Such events are not necessarily detrimental to the European identity if the Europeans are not asked to give up their national or regional identity – if they are asked to go beyond it, what would probably pull them closer together. In the other words, it is suggested to be created a community in which diversity is not a problem, but a character in order that national-regional differences would become integral parts of the feelings to be European [6].

In 2005, the internet domain .eu was launched under the title Your European Identity. In order to register a .eu domain, one must be located in the EU [41]. This step indicates common gravitation towards switching to a European mentality. The success of the .eu domain system has been extremely positive. The same is expecting and from the policy of labeling the EU products as Made in the European Union.

Finally, the common EU’s currency known as the Euro (€) has to play one of the real factors in making the EU’s citizens feel like the Europeans.[xi] The existence of a common EU’s currency and monetary union (the EMU) means above all an acceptance to live in a common state (the USE) what is and the final political purpose of the whole process of the so-called “Europeanization” from 1951 onwards. In the other words, to accept to live in a common political unity in a form of a state with the others above all means acceptance of common reciprocity and solidarity based on a common (pan-European) identity.[xii]

Identity, pan-Europa and civilizational Europe

The identities are extremely important for people. Many people use a group identity and protectiveness to bolster their self-esteem while others use a collective identity to help them in the understanding of the world.

The meaning of Europe and, therefore, of European identity is very problematic and contested but a specific pattern of historical evolution gave the continent a distinctive identity, although this common pan-European identity is in practice divided between West and East Europe. Someone can say that at the base of European civilizational identity is the notion of modernity and progress, whereby society is turned to the future development of improvements.

What is official Europe? In the Western academic literature, it is clearly pointed out that West European integration after WWII is central to the concept of Europe which can be called “official Europe” [60]. The EU is one of the most successful (up today) supra-national institutions in European history. However, the EU’s eastward enlargement remains quite problematic or many reasons f which a common pan-European identity is only one of them. For official Europe, the definition of something to be labeled as European-ness is founded on the so-called Copenhagen criteria: democracy of Western liberal type, the rule of law, human rights, full citizenship rights for national minorities, and functioning liberal market economy. All of those criteria are, however, the product of Western liberal thought aiming to impose a Western cultural and ideological supremacy across the continent backed by the military forces of the NATO. As the geopolitical answer, Russia sought after 1991 to make the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) as a kind of counterbalance to such Western hegemonic and neocolonial designs. In practice, the eastward enlargement of both the EU and NATO is threatening to isolate Russia, although both organizations are trying to sweeten their Russophobic policies. The attempt of Brussels to create a common pan-European identity based on Western values is only one of many applied techniques to turn Central and East European nations against Russia as “non-European” and rather “Asiatic” state which is allegedly not fitting to the standards of being European.

Nevertheless, the programs for both EU’s and NATO’s eastward enlargements are the powerful geopolitical catalyst of change in Central and East Europe during the last three decades but in turn, forced an agenda of reforms and adaptation on both the enlarging institutions and concepts of identity. The EU’s eastward enlargement, in other words, challenged the Old continent to rethink what it meant to be European leaving the most East Europeans in the lurch. The eastward enlargement is very much criticized by the Western thinkers too (for instance, Garton Ash) as it changed an already well-functioning peaceful and prosperous West European community of nations [61]. For sure, the new Member States from the East (up to today 13) will take decades to be fully integrated into “Europe” and already there are clear signs that such situation reduced the appetite for further enlargement and, therefore, searching for new types of European identity.

Nevertheless, the programs for both EU’s and NATO’s eastward enlargements are the powerful geopolitical catalyst of change in Central and East Europe during the last three decades but in turn, forced an agenda of reforms and adaptation on both the enlarging institutions and concepts of identity. The EU’s eastward enlargement, in other words, challenged the Old continent to rethink what it meant to be European leaving the most East Europeans in the lurch. The eastward enlargement is very much criticized by the Western thinkers too (for instance, Garton Ash) as it changed an already well-functioning peaceful and prosperous West European community of nations [61]. For sure, the new Member States from the East (up to today 13) will take decades to be fully integrated into “Europe” and already there are clear signs that such situation reduced the appetite for further enlargement and, therefore, searching for new types of European identity.

Europe was and is divided politically but the new sources of division came into force. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that Russia, for instance, is part of at least a broader concept of European civilization. Russian literature and art have surely embellished European cultural space, its music and philosophy are an indivisible part of European thinking, and the Russians are firmly part of the European history, customs, and tradition. Consequently, such cultural unity is overcoming political divisions, geographical borders, and geopolitical designs. Of all concepts of Europe and European identity, civilizational Europe is probably the weakest one measured by Brussels’ standards of European-ness. Politically speaking, after the Cold War 1.0 division of the world and the Old continent, the people of Europe can freely argue that all inhabitants of Europe and Europeans now. However, the political practice of Cold War 2.0 made clear that there is no unanimity over the question: Who is distinctively European in Europe? In practice, West Europe, and particularly the EU, became kind of ideal to which the biggest part of the Old continent aspires.

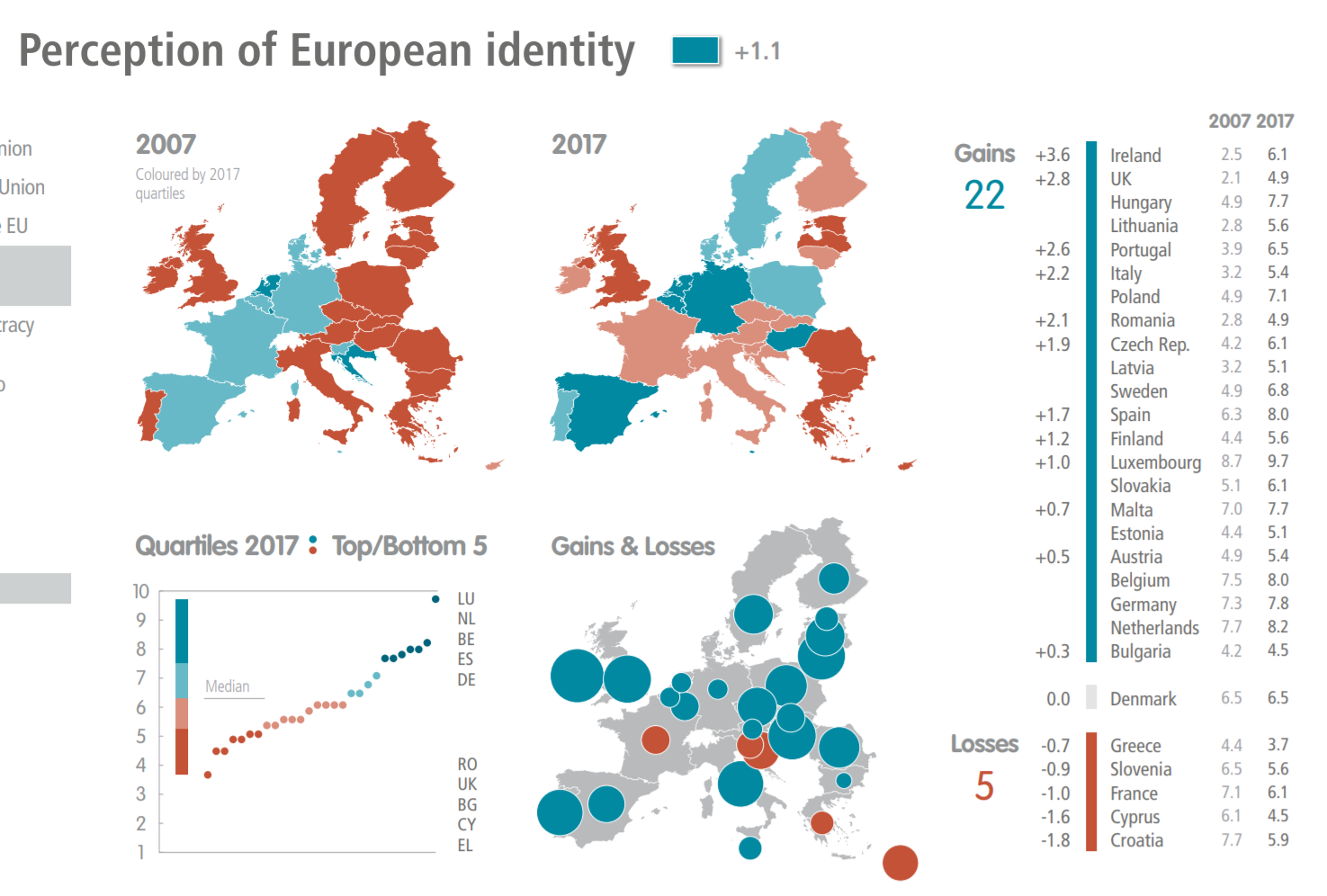

European integration under the umbrella of the EU is perceived by many Europeans as a potential threat to their basic (national, regional or local) identity or identities. The degree to which the EU’s citizens worry that the European integration project can bring about a loss of national identity and culture is quite high. In fact, according to many research results of the public opinion, exclusively national identity seems to vary widely across the EU. While some of those who see themselves exclusively in national terms and those who fear the loss of national identity are openly hostile to the EU, it is more generally the case that such fears translate into ambivalence toward the EU rather than outright hostility. Nevertheless, European integration is seen by many EU’s citizens as a threat to one of the key identities of the Europeans – their national identities as the final task of the European integration within the framework of the EU is, in fact, political rather than economic. Finally, the exclusiveness of identity may be more important in explaining hostility to the EU and its project of the European unification.

Final remarks

The European identity seems fit to take on a new life given the EU’s continuous expansion. The workable concept of common pan-European identity should fall within the framework set by the theory of ethnic indifference which allows citizens not to give up their national identity but to expand their identity into a pan-European one. Different proponents support different views of the European identity, be it Europe as space of encounters, Europe of culture or Europe of citizens. It is particularly important not to ostracize national minorities in the process of defining common pan-European identity.

Technically, it is suggested that for a definite common pan-European identity to emerge one must focus on the young generations. These are the generations that are willing to adapt to change and these are the generations that will carry forth the European identity followed by the EU’s (and of the NATO) ideological and geopolitical aims especially regarding Russia. Through free mobility of labor, the lack of visas, and intercultural exchange programs, the opportunities to experience another nation are immense. Communication is easier than ever with technological advancements, such as the internet, and the emergence of English as an auxiliary language has allowed citizens to clearly communicate with one another. These are the advancements that can enable common pan-European identity in the future. Shared values and common pop-culture surely help link the continent. Probably, if in the future the Europeans (of the EU) would further unite in their diversity it could be expected that clear common pan-European identity will emerge.

It is true that the EU always needed a political purpose beyond just trade. Without political purpose, the EU construction will start to fall apart [29]. To create and to maintain common pan-European identity (alongside with particular national and regional identities) is a crucial project of keeping the whole political construction of the EU (or some kind of the United States of Europe in the future) together for the very reason that without common identity there is no common solidarity and common wish to live together within the same political framework (state).

It has to be noticed that there are four existing types of states in the world in relation to the nature of their subjects:

1) “People-nation state” – organized on the ethnic basis of the state’s inhabitants.

2) “Cultural-nation state” – organized on the basis of commonly shared culture by its subjects.

3) “Class-nation state” – organized on the ground of the class belonging of its subjects.

4) “Nation of the state’s citizens” – organized politically on the normative basis of legally interpreted individual rights [38].

In this context, many researchers strongly believe that the only successful, long-standing and democratic type of the state building applied in the case of the United States of Europe is the last fourth type for the reason that only a Constitutional patriotism can be a functional framework for the creation of common pan-European identity which has to be followed by the change of the political system of the EU in order to be more compatible with the common pan-European identity.[xiii]

Reposts are welcomed with the reference to ORIENTAL REVIEW.

Endnotes:

[i] On this problem, see in [44].

[ii] “Erasmus” (European Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) program was proposed by the European Community’s (the EC) Commission in 1985 and was accepted by the EC’s Council in 1987. The European Free Trade Association’s (the EFTA) member countries became part of this program in 1991. “Socrates” program of the EU works from 1995. The task of this program is to make better EU’s policy of enlightenment. “Erasmus” program became the most important branch out of six breaches of the “Socrates” program to which it is given 55% out of total “Socrates” program budget.

[iii] On this issue, see in [27, 36]. “Socrates” is a program designed formally to encourage innovation and improve the quality of education through closer cooperation between educational institutions in the EU [62].

[iv] On the evolution of the labor law within the EU, the distinct national and regional approaches to the question of employment and welfare, and the pressures for change within a further enlarged EU, see in [8, 47].

[v] About the free movement of persons and workers in the EU, see in [63].

[vi] On the European transnational identity and citizenship, see in [14, 31, 50].

[vii] On the question of the English language as a modern lingua franca, see in [5, 21, 39].

[viii] On the question of language and language policy of the EU and within the European continent, see in [43, 45, 54].

[ix] On the role of transnational mass media for the creation of the pan-European identity, see in [34].

[x] On Eurovision Song contest and European identity, see in [13, 28].

[xi] On the Euro currency, see in [12].

[xii] On this problem, see in [40].

[xiii] On the EU’s political system, see in [48]. However, the politics and policies of creation of the common pan-European identity have to take into consideration and the question of immigrants’ integration within the political framework of the EU and the USE. On perspectives for common European migration policy, see in [23].

Comments