The origins of Czechoslovakia (1918−1920)

Czechoslovakia gained its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. Even though the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was one political entity, the Austrian part and the Hungarian part existed under a Dual Monarchy. Each half of the empire had a large amount of control over their area independent of the other half of the country. The differing policies of the Austrians and the Hungarians had a strong impact on the state of what is now the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. In particular, the Czech industry was developed, while Slovakia remained a mostly agrarian area managed by a Hungarian elite. This led to two main differences between the Czech and the Slovak side of the country that would affect the policies of the Government:

- One was that Slovaks had a much less developed civil society compared to the Czechs since they were unable to develop one while being part of Hungary.

- Secondly, Slovakia remained a mostly agrarian society, in part due to its position as the breadbasket for the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also because of the lack of money that was invested in the area.

Slovakia’s history on the borderlands between the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire affected its development. Slovakia was unlike areas of the Czech Republic which had been able to develop industry not only due to their resources but due to their location away from war actions and closer to the major European cities, and their central location within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Slovakia had been developed in the history of the Kingdom of Hungary as a barrier against the advancing Ottoman Empire toward Central Europe. After the Ottoman Empire was no longer a danger due to its severely weakened state and had lost lands in the Balkan peninsula, money was invested elsewhere in the Habsburg Monarchy. While the western part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was developed economically, Slovakia remained predominantly an agricultural society. Unlike Slovakia, the Kingdom of Bohemia (later the Czech Republic) had at one time existed as an independent (till 1526) and the autonomous country as recently as the early seventeenth century (till 1620). It became part of the new Austrian Empire in 1804, and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 until Czechoslovakia became proclaimed as an independent state in 1918.

The development and spread of nationalism in Europe during the mid-19th century led indirectly to the development of a Slovak national identity. This was in part due to the fears of Magyarization which were felt by all minorities within the Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire and later since 1867 a Dual Monarchy. In 1848, the governing body of Hungary issued the so-called “April Laws” which essentially established Hungary as an autonomous area within the Austrian Empire, which the central Government of the Austrian Empire was unable to address due to the numerous nationalistic movements that were spreading through its empire. The Hungarian Government then used these policies to strengthen Hungarian identity by the engaged policy of Magyarization. This had numerous effects on many different aspects of life, for example, the use of Hungarian language in education. However, the development of a Slovak national identity did not begin in earnest until Czechoslovakia became a country, and resistance was felt towards a Czechoslovak identity, which Slovaks felt was the promotion of a Czech identity at the expense of the Slovak one.

Czechoslovakia gained its independence in a series of steps. Even before the creation of the common state, the idea of Czechoslovakia was advocated by Czechs and Slovaks living abroad (in the USA). This idea was also supported by the eventual winners of WWI for various geopolitical and other reasons:

- One of the reasons for this support was the idea that multinational empires have to be replaced by the national states.

- Monarchies have to be replaced by democratic Governments of the republics.

- Countries had to justify their legitimacy to the rest of the world and one way of doing this was by stating a certain ethnic group’s claim to an area due to their historic presence in that land.

- Another reason why Czechoslovakia was advocated by emigrants was because of a political-ideological concept of the Pan-Slavism. Though the concept has played a role in the motivations of Russian policy in East Europe and especially at the Balkans, the extent to which it contributed to the idea of Czechoslovakia is not agreed upon, but it surely influenced some thinkers. Pan-Slavism was used during the Great War to encourage some of the captured Slovak soldiers, at that time as soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to instead fight against it. After Czechoslovakia became independent in 1918, however, the idea of Pan-Slavism was not strongly advocated for, losing favor with those who had supported it.

The Czech lands gained independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire first. Slovakia proclaimed its independence and desire to join the Czech country two days later. However, this process took more time. The Czech troops which had been in Slovakia were defeated by the Bolshevik army, which briefly occupied part of the country and installed a puppet Soviet Government. The Hungarian forces were able to force the Bolsheviks out of the country but ended up losing possession of the country after the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty, which created the border between Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Part of the justification for the foundation of Czechoslovakia was to give the Czechs and Slovaks their own country, compared to the Austro-Hungarian Empire where they were denied rights due to their minority status. Nevertheless, due to the way that Czechoslovakia was established, it was to have its problems with minority populations (Germans and Hungarians) within its borders and choosing the best way of handling them.

Czechoslovakia was the Central European state which emerged on the political map as a consequence of the collapse of the Dual Monarchy (the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The country’s formal independence was declared on October 28th, 1918, and confirmed at the Paris Peace Conferences, on September 10th, 1919. The final borders are fixed by the 1920 Trianon Peace Treaty.

The country was composed of two different parts:

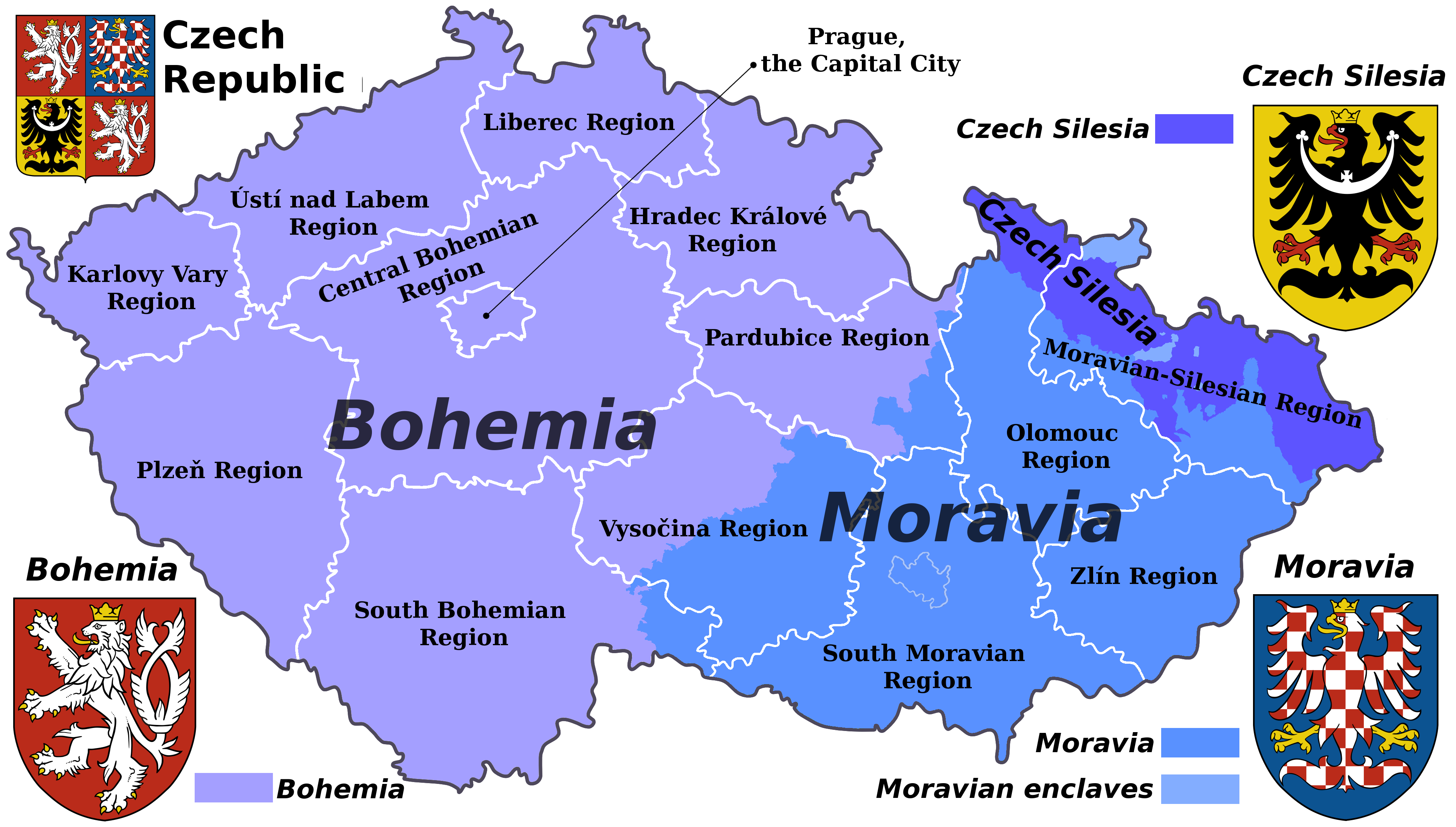

- The economically advanced historical regions of Moravia, Bohemia, and parts of historical Silesia, which made up the Czech lands (former part of Austria).

- The industrially backward Slovakia, including parts of the even poorer Carpathia (former part of Hungary).

The very fact was that the new state became extremely ethnically heterogeneous as consisting of 66% Czechs and Slovaks, 22% Germans, 5% Hungarians, and 0,7% Poles followed by other ethnic groups. Such ethnic background alone obliged the new state to pursue an extremally liberal policy for the very reason to reconcile its numerous minorities. This liberal trend was reinforced by its educated intellectual leadership under Thomas Masaryk and Edvard Beneš. Their liberal politics have been fully supported by the well-developed and prosperous middle class of the Czech lands.

In the 1920s, Czechoslovakia experienced greater economic development in comparison with all other Central European economies. Due to the Little Entente Pact backed by France and its good relations with Paris, the country succeeded to buttress its position in foreign affairs. Nevertheless, in the 1930s, after the Great Economic Depression in 1929−1933, it became extremely difficult to save the country from the rise of Nazism, fascism, and other forms of autocratic political systems that have been surrounding the country. The new Germany’s Nazi movement, in particular, attracted the Sudetenland Germans in north-western Bohemia, who started to demand more autonomy and self-government ever more aggressively. However, inter-ethnic grievances as well as existed from the Slovak part of the country. As the educated middle class was almost Czech, the Slovaks found themselves underrepresented in the political system of the country and, therefore, they started to demand more autonomy for the Slovak half of the state.

The Interwar Years and the question of the Sudeten Germans (1919−1938)

Czechoslovakia went from being part of a multi-national Austro-Hungarian Empire to being a country with sizeable ethnic minorities. The three largest ethnic groups in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period were the Czechs, at about 6.5 million, the Germans at about 3.1 million, and Slovaks at 2.2 million. The remaining ethnic groups included the Hungarians, Poles, Ukrainians, Roma, and others. The relationship between the Czechoslovak Government and the Sudetenland Germans was tense and remained so throughout all interwar years. The reason for this was that the Germans did not accept their inclusion within the new country after WWI, and feared that their identity would be lost. The Slovaks, on the other hand, were more accepting the new state for at least two crucial reasons:

- There was the belief that may not have gone far as Pan-Slavism but still advocated the Czechs and Slovaks being branches of the same family.

- Czechoslovakia was seen as a preferable alternative to being ruled by the Hungarians, under whom they had to deal with Magyarization and the prevention of the development of a Slovak national identity.

The Sudetenland Germans created a problem for the Czechoslovak Government due to their size and lack of commitment to the idea of the new state. One way in which the tension was reduced was by Czechoslovakia’s political stability and economic strength during the interwar years. As a matter of fact, the Sudetenland Germans faced a higher standard of living during that time than the Germans in Germany. However, this did not prevent the wide acceptance of Nazism from spreading to the region when the Nazis came to power in Germany. The Sudetenland Germans also developed strong anti-Czech policies, especially during WWII. The adoption of Nazism was in contrast to the political leaders of Czechoslovakia who, unlike many other countries during the period who attempted different types of autocracy, managed to maintain its identity as Central European liberal democracy.

The vigor with which Sudetenland Germans did not want to be a part of Czechoslovakia also led to the second problem. Two types of policies were pursued in order to reduce the risk of conflict arising from the Sudetenland Germans:

The vigor with which Sudetenland Germans did not want to be a part of Czechoslovakia also led to the second problem. Two types of policies were pursued in order to reduce the risk of conflict arising from the Sudetenland Germans:

- One of these sets of policies had to do with autonomy. The Czechoslovak Government decided to not enter into a federation type of state organization. Such a decision was done for the purpose that the Sudetenland Germans would not gain more political power from which to further strain their relationship with the Czechoslovak Government. Nevertheless, this also meant that the Slovaks could not have more political and legal autonomy too. This may not have initially been a problem because of the lack of development of a Slovak identity and civil society during the centuries of Hungarian rule.

- However, the second type of policy contributed to the development of these, something the Czechoslovak Government had not anticipated. A way to strengthen not only the Czechoslovak Government against the Sudetenland Germans but to strengthen the country itself was to develop Slovakia and to promote a shared Czechoslovak identity. Firstly, if the Czechoslovaks were counted as one ethnic group within the country then the ratio of Czechoslovaks compared to the Sudetenland Germans would be larger than looking at just Czechs or Slovaks compared to the Germans. Secondly, an economically strong country was believed to diminish the potential for grievances against the Government.

Due to the lack of development on the Slovak side of the country, money traveled almost exclusively from West to East in order to develop the Slovak economy. Money also went into the development of schools and public institutions and contributed to the development of a Slovak intelligentsia.

Interwar Czechoslovakia was still not overcome by internal collapse, however, by the 1938 Munich Agreement, when the Sudetenland was annexed by Nazi Germany, and the lands inhabited by the Polish minority (Teschen) and Hungarian minority were annexed by Poland and Hungary respectively.

The Sudetenland Germans strongly supported the inclusion of Sudetenland into Germany, since they still retained a strong German identity. At the 1938 Munich Conference, leaders from four countries (Germany, France, UK, and Italy) met in order to discuss what to do about the Sudetenland. On September 30th, 1938, Sudetenland was incorporated into Germany. By giving Sudetenland to Germany, other countries were hoping that the German desire for more land would be satisfied. The Sudetenland had a large number of German citizens where roughly two-thirds of its population supported inclusion into Germany. However, it also brought into question the strength, and legitimacy of the Czechoslovak Government. Nazis working in Czechoslovakia had advocated for autonomy for the region. Instead, the Czechoslovak Government granted more minority rights but refused to designate Sudetenland as an autonomous region.

By losing it to Germany, the Czechoslovak Government was perceived as weak. By this time, the Slovaks had developed not only their class of intelligentsia but a more cohesive idea of Slovak national identity and independence. One of the crucial geopolitical consequences of the 1938 Munich Agreement was that it emboldened individuals who supported the creation of an independent Slovak state instead of weakened Czechoslovakia which did not get the European support for its territorial integrity.

Nevertheless, while on one hand the Slovak nationalists were emboldened by the loss of Sudetenland in the 1938 Munich Conference, they also now faced a dilemma. It was suspected that Nazi Germany would not be content with just the acquisition of the Sudetenland. The German idea of Lebensraum based on the acquisition of land for the German people, along with the expulsion or execution of other ethnic groups considered to be racially inferior, also led to the conclusion that the Nazis would seek to acquire more land. The Czech members of the common Government were strongly against Nazism and it was suspected that if the Germans defeated Czechoslovakia, policies instituted by the new German Government would harm all of the citizens of Czechoslovakia. However, the Slovaks had a way out of this predicament. The German Government made clear to the Slovaks that they would be willing to support the formation of an independent Slovak state instead of a common one with the Czechs. The Slovaks had to choose whether to stay part of Czechoslovakia or to proclaim their formal independence under the German patronage.

On March 14−15th, 1939, the German army invaded the rest of the historical Czech territories within Czechoslovakia with the creation of the German protectorate over Bohemia and Moravia. These two historical provinces became relatively autonomous, with a puppet President Emil Hácha. However, the Nazi German brutal administration suppressed the Czech educated and middle classes during the protectorate time (1939−1945).

To be continued

Comments