The Chinese-Indian Cold War Of 2015

It’s politically taboo to speak about it in the global media for a variety of reasons and respective interests, but China and India have been engaged in a very dynamic Cold War since at least the beginning of this year. The earlier-described rivalry over the Indian Ocean states is a component of this proxy conflict, but most of it is actually playing out in mainland Asia, specifically all around the Indian periphery. While there was geopolitical tension between both giants for some time already, everyone seemed to have assumed that Asia was ‘big enough’ to accommodate both of them, and it very well still might be, but what’s taking place at the moment is an unquestioned competition over spheres of interest that will surely define at least the coming decade.

Myanmar

The historically military-run Southeast Asian state had been a stalwart client of China’s for the past two decades, but it’s surprising 2012 decision to ‘voluntarily’ (with intense American behind-the-scenes wooing) engage in a self-initiated ‘pro-democratization’ process has moved it further away from its former ally. In the meantime, while China still remains an important partner of Myanmar, other actors have swooped in to ‘grab a piece’ of the formerly reclusive nation’s market and resources for themselves, chiefly India. The most important point of bilateral cooperation between India and Myanmar is the Trilateral Highway that links them with Thailand and was recently opened in September.

The project could accurately be described as India’s “ASEAN Road” and is an important (if undeclared) component of the Cotton Road strategy to expand New Delhi’s economic partnerships. The long-term idea here is that India could integrate with its ASEAN counterparts with time and ‘block’ any possibility for China to achieve or retain a controlling economic ‘stake’ over any of these states. The key to it all runs through Myanmar, since the land-based route is envisaged to create a future corridor of investment that links the SAARC and ASEAN marketplaces firmly together, and this country has thus been in the crosshairs of Chinese-Indian competition for the past couple of years already. Additionally, it is the only one of the examined ‘battlegrounds’ to not experience a significant “pro-China” or “pro-India” event so far this year, with all the others having done so in increasing intensity.

Sri Lanka

Former President Rajapaksa pushed forward the presidential elections earlier than they were initially scheduled, and committed to holding them at the beginning of January 2015. He had earlier felt assured that he’d win given that he presided over the central government’s (bloody) unification victory in settling the decades-long Tamil rebellion. To his utter surprise, Minister of Health Maithripala Sirisena defected from the government and announced in November 2014 that he’d be running as the opposition’s main candidate. In what may stand to be one of the quickest electoral reversals in recent South Asian political history, Rajapaksa lost the election by 47.58% to Sirisena’s 51.28%.

The stunning aftershocks of this vote immediately extended into the international arena, with Sirisena going through on his pre-electoral promise to suspend China’s $1.4 billion investment in port infrastructure, ostensibly citing “environmental concerns”. While the government flip-flopped to a more pragmatic rhetoric about the project after China pledged a $1 billion grant to the country, it has yet to reauthorize the project, and construction remains at a standstill to this day. Sirisena has been characterized as trying to “balance” between China and the West, but considering that one of the top nodes in China’s New Silk Road has been indefinitely frozen, it’s apparent which side he’s strategically leaning closer to and which one experienced the largest relative loss since he came to power.

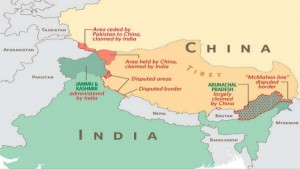

Pakistan

There is no realistic chance whatsoever that Pakistan would retreat from its pro-Chinese strategic orientation, so it’s not exactly a ‘battlefield’ between Beijing and New Delhi. However, in the context of the Cold War between them, an important event occurred in April when President Xi visited Pakistan and officially announced the $46 billion Pakistan-China Economic Corridor. There’s no way to overstate exactly how significant of a decision this was, since it firmly solidifies the Chinese-Pakistani Strategic Partnership and makes Islamabad the geostrategic replacement for Naypyidaw in terms of Beijing’s Indian Ocean strategy. China is confident that no amount of bribes or cajoling could convince Pakistan to ‘pull a Myanmar’ and reverse its strategic orientation, so it knows that it has a dependable anchor in actualizing its much-needed grand strategy in this vector.

From the Indian zero-sum perspective, the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor is one of the worst developments that could ever happen, since not only does it intimately tie its two main rivals together for the indefinite future, but it also ensures that Pakistan would never cede its administered territory of Kashmir, as this is the critical connector directly linking it to China. It’s hard to fathom exactly how strong of a diaphragm blow this was to Indian policy makers, but it probably left many of them speechless in despair and scrambling to devise a ‘counter-measure’, although of course, there’s nothing that India could conceivably do to make China experience a symmetrical feeling of unease. However, the ASEAN Road does come close in a strategic sense, although that in and of itself doesn’t threaten China’s perpendicular energy corridor from Myanmar’s Indian Ocean shores or seemingly forever preclude Beijing from reasserting its influence in the country. Furthermore, Myanmar isn’t a part of China’s identity, while the Kashmir conflict is an integral part of India’s, and Beijing just snuffed out any remaining dreams that New Delhi may have had (no matter how distant) of ever gaining control of the Pakistani portion.

Bangladesh

India’s “response”, if one could characterize it like that, to China’s deepening ties with Pakistan was to send Modi to Bangladesh to finally resolve the two sides’ border disagreements and pave the way for an overdue strategic (but hopefully equal) partnership between them. As the author wrote at the time:

“Modi’s visit to Bangladesh was an absolute success for both countries, as they were able to finally resolve their 40-plus-year border dispute and enter into a mutually profitable coastal shipping arrangement. The mainland breakthrough secures their mutual border by finally delineating it and resolving the undefined status of around 50,000 people. With no more territorial issues between them, both sides can now enter into a golden age of economic and security relations, which will have an extraordinarily positive impact on India’s Northeast.

As per the coastal shipping deal that was just clinched, India can now directly use Bengali ports to facilitate trade with its far-flung states, thus avoiding the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor that barely connects the region to the rest of the country. The cross-Bengali route enables it to tighten the central government’s control over the peripheral and separatist regions, and since Dhaka is now on board with India’s strategic goals, it could partake in cooperative operations with New Delhi to secure its side of the border in conjunction with any forthcoming anti-terrorist crackdown there.”

In a nutshell, what Modi had done was to bring Bangladesh ‘in from the cold’ when it comes to regional relations and move it a lot closer to India at China’s relative expense. Up until that point, Bangladesh had depended on China to counter-balance what its leadership genuinely felt were the hegemonic intentions of India (despite New Delhi helping it to gain independence from Pakistan), but that entire hedging structure appears to have gone out the window with this latest agreement. Bangladesh is of course privy to conduct its national policies however it so chooses, but in the conditions of the Chinese-Indian Cold War, it’s (unintentionally) giving India a huge advantage by allowing it a long-sought-after shortcut in supplying and developing its Northeast, which in turn enhances the viability of the ASEAN Road and India’s soft power projection in that region (considered to be to China’s strategic detriment).

Nepal

This Chinese-Indian Cold War only recently hit the Himalayan nation, and ironically enough, India’s misguided policies appear to be the reason why the historically friendly country is now lunging into Beijing’s hands in order to spite New Delhi. The author also wrote about this topic in a prior article, but to briefly review, Nepal’s new federative constitution was met with dismay by India and the almost culturally identical Madhesi ethnic group that lives along the shared Terai (grassland) border. They allege that the seven states comprising the new federation are not inclusive to their interests and do a lot to undercut their representation in any future government, despite them being around 30% of the population (40% of whom aren’t legal citizens) and controlling the key access points for trade to India (through which the vast majority of its international trade is conducted). The subsequent riots that have rocked the border region contributed to Indian truck drivers refusing to cross into Nepal, although Kathmandu insists that this is actually a de-facto blockade on the part of New Delhi.

This Chinese-Indian Cold War only recently hit the Himalayan nation, and ironically enough, India’s misguided policies appear to be the reason why the historically friendly country is now lunging into Beijing’s hands in order to spite New Delhi. The author also wrote about this topic in a prior article, but to briefly review, Nepal’s new federative constitution was met with dismay by India and the almost culturally identical Madhesi ethnic group that lives along the shared Terai (grassland) border. They allege that the seven states comprising the new federation are not inclusive to their interests and do a lot to undercut their representation in any future government, despite them being around 30% of the population (40% of whom aren’t legal citizens) and controlling the key access points for trade to India (through which the vast majority of its international trade is conducted). The subsequent riots that have rocked the border region contributed to Indian truck drivers refusing to cross into Nepal, although Kathmandu insists that this is actually a de-facto blockade on the part of New Delhi.

In response to desperately dwindling fuel supplies and the inability to receive its regular imports from India, Nepal looked northwards to its Chinese neighbor for help, and Beijing swiftly responded by agreeing to provide 1.3 million liters and signing a different deal “to fulfil 33 per cent of Nepal’s demand in the face of India’s monopoly.” In one fell swoop, Nepal, a country which had always had very close relations with India throughout most of its history (but which some have criticized as being more of a proxy-patron nature), now seems to be fleeing from its larger neighbor and looking at China to provide a geo-economic counter-balance. In fact, one could even describe Kathmandu’s latest actions as constituting an acute pivot on Nepal’s side, albeit one which was forced upon it by India and its implicit support of the Madhesi agitators. New Delhi’s actions have made such an impression on Nepali decision-makers that the Deputy Prime Minister recently took to accusing India of planning to annex the Terai, thus reflecting what can be perceived to be an influential train of thought prevalent in Kathmandu nowadays. If China can establish preeminent influence over Nepal with time, then Beijing would also indirectly gain control over the strategic Karnali and Koshi rivers that nourish many of the 200 million Indians that live directly south of the border.

Maldives

As understood from the strategic framework hat’s been meticulously explained up to this point, it’s difficult to find fault with the claim that the Maldives’ current crisis is yet another outgrowth from the Chinese-Indian Cold War. Approached from this angle, the event and the run-up to it takes on a completely new understanding than the conventional one being promulgated in the mainstream media. For all intents and purposes, Nasheed and his Maldivian Democratic Party take on the role of pro-Indian, anti-Chinese proxies in the island chain, with incumbent President Yameen representing the most pro-Chinese force the country has ever seen. Disturbed at the rapid advancement in bilateral relations between the Maldives and China, India looks to have wanted to use its or its Western ‘partners’’ “grassroots” forces in order to exert pressure on the government and motivate it to ‘moderate’ what New Delhi believes to be its uncontrollable pro-China policies.

An imprisoned Nasheed serves as a rallying symbol similar to how an imprisoned Suu Kyi and Tymoshenko once did for Myanmar and Ukraine, respectively, and it also creates a semi-believable pretext for damaging the reputation of the present government. If India doesn’t succeed in moving the Maldives away from China’s sphere of influence and reclaiming its sway over them and the geostrategic waters that they occupy, then its fallback plan is to ‘isolate’ the President by having him painted as an international pariah. Simply jailing Nasheed isn’t enough to turn the Western world against Yameen, but if the government can be provoked into some kind of highly publicized crackdown action that gets filmed and shared on social media (perhaps beating a “protester” on the street, or shooting a terrorist suspect), or if professional provocateurs succeed in a false-flag attack, then it would dramatically increase the chances that Western governments would issue “travel advisory warnings” or perhaps outright demand that their citizens stay away from the country.

The objective here is to hit the country’s tourist sector (the lifeblood of its economy) as hard as possible, hoping that this will lead to increased anti-government dissent and active opposition with time, although the fact that Chinese tourists overwhelmingly outnumber all others could help to cushion the economic blow and delay its full effect. Regardless, the end goal is to have the people do to Yameen what they did to Nasheed, albeit this time under internationally manufactured circumstances for geopolitical ends. Another difference would be that the police and military know the true extent of the crisis’ seriousness and how it’s not just a ‘paranoid delusion’ of an island ‘dictator’, making it extremely unlikely that they’ll turn against him in the same way they flipped on Nasheed.

The last thing to say about the Maldives’ Crisis and how it relates to the Chinese-Indian Cold War is that there’s no evidence other than circumstantial that India has anything to do with the assassination plots against Yameen. Like what was mentioned in Part II, it could very well be that the US and UK are handling this part of the operation, and they might not have even informed their Indian ally about the extent that they’re willing to go to see China’s Indian Ocean ally removed from power. They may or may not have – this information isn’t known and likely never will be – so it’s difficult to assess the level of complicity that India has in that part of events.

Nevertheless, it’s without a doubt that India would prefer for Yameen to put the brakes on his ties with China or for a different, less Chinese-friendly government to be in power in the Maldives (one which would be the Maldivian equivalent of Sirisena’s in Sri Lanka). The logical question then becomes one of exactly how far India is willing to go to achieve this, and if it would restrain itself to Color Revolution tactics (as it failed to productively apply in Nepal so far) or if it would actually try to assassinate the President. Another related question is the degree to which the US and UK are involved in this operation and the level of collaboration between them and India, as well as whether New Delhi is aware of (if not directly complicit in) what might actually be an assassination plot that’s thought of and about to be carried out by the West.

Concluding Thoughts

The Maldivian Crisis might seem like an odd, isolated event to observers that are unaware of its broader geostrategic contexts. To most of the Western audience, it looks like an ‘island dictator’ has enacted a draconian state of emergency in order to defend against ‘paranoid’ assassination plots and a purportedly growing ‘pro-democracy’ movement, but in reality, the situation is completely different than how it’s being presented in the mainstream media. What’s actually happening is that one of China’s newest yet most important strategic partners is under threat of having a Color Revolution sweep him from power in favor of a pro-Indian replacement, and to add to the drama, at least three “backup” assassination plots have been uncovered so far. The threat to President Yameen and the national security of the Maldives is very real and urgent, and it’s not for naught that he enacted the last-minute state of emergency in order desperately stem off what would have surely been(and might still turn out to be) a deadly spiral of destabilizing violence.

The unspoken conflict being played out through proxy here is the Chinese-Indian Cold War, the geopolitical dynamic of which has been enormously impacting regional affairs ever since the beginning of this year. Part of the reason for this is natural Great Power rivalry (Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh), but looking at the instances of Nepal and the Maldives, it’s clear that these two particular destabilizations were ‘unnecessary’ and has been taken to extremes by those responsible for it. China isn’t the culprit in either of these two cases – its strategic influence in Nepal was minimal before its constitutional crisis and its partner in the Maldives is on the defensive – thus making it convincingly look like India is the one that provoked the events, to accuse it of the very least that it might be guilty of.

Still, another less-discussed factor can’t be discounted, and it’s that some third-party force has involved itself in between China and India’s interests in these two states and is trying to play kingmaker for whatever manipulative ends they have in mind (perhaps even employing disloyal elements of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs to achieve this). There’s nothing but speculation to support this theory, but it does seem semi-plausible when one considers how out-of-character India’s actions have been in Nepal, and if the author’s intuition is at least somewhat correct, then in the Maldives as well. It could also simply be that both of these risky (and failing) foreign policy ventures are simply the result of a ‘new’ style of foreign policy thinking, or perhaps that they’re how the Modi Administration planned on approaching regional affairs all along, but the fact that India’s actions towards its two long-standing allies are so out of touch with how they’ve traditionally been applied does engender probable cause for suspecting either foul play or outright professional negligence.

The consequences of China and India’s Cold War, especially in its latest violent manifestations in Nepal and the Maldives, could prove to be disastrous for BRICS and SCO unity, the latter group of which India just applied to finally join this summer amidst the intensifying regional struggle between both sides. If New Delhi and Beijing continue on their present trajectory of destabilizing regional rivalry (in the last two recent cases of Nepal and the Maldives, instigated or provoked by India), then a definite rift will surely emerge between them and their mutual multipolar organizations (more so BRICS in this case than the SCO) could prove to become unworkable as a result. As the strategic partner of both of them, Russia has the opportunity to help mitigate tensions so that they don’t interfere with multilateral efforts that are to everyone’s advantage, but this strategy only works so long as both sides genuinely want to cooperate for the common multipolar good. If Modi is acting under the influence of the West and intends to confront China to the point of sabotaging the BRICS and SCO, then there’s nothing that Russia could do to convince him otherwise, and it must hedge its bets accordingly in that case.

Judging by India’s reckless foreign policy adventures in Nepal and what increasingly looks to be the Maldives as well, the New Cold War might have taken on a new, more complicated angle. Whereas earlier it could be simplified as the US/West vs Russia/China, now it appears as though India has joined the US/West in trying to actively counter China, although it has yet to turn its back on Russia. If this turns out to be the case, then that would make the Russian-Indian bilateral relationship perhaps the most important in the world today, since these would be the two opposing ‘alliance members’ that still have relatively pragmatic and positive relations with one another (for now). They could serve as bridges of dialogue and could possibly become the fulcrums of their respective ‘blocs’, provided of course that neither begins behaving in a hostile manner towards the other. However, the unprecedented pressure that both of them will likely feel from their geopolitical partners (US/West as it relates to India, and China as it relates to Russia) to resolutely take a stand against their respective rival (Russia and India, for reach of the respective aforementioned ‘blocs’) might be too much, and they could find themselves wittingly or inadvertently setting off a rapidly down-spiraling security dilemma that breaks the two apart. If that dismal scenario comes to pass, then a high-stakes and high-tension system of bipolarity may come to regretfully replace the high hopes that many have long had for a peaceful multipolar future.

Pingback: Indian Ocean As A Prize Or Crisis Of Multipolarity? (I) | Alternate NEWS Blog

Pingback: Indian Ocean As A Prize Or Crisis Of Multipolarity? (III) | Alternate NEWS Blog

Pingback: ASEAN And The New Cold War Battle For Eurasia’s Economic Future (I) | Oriental Review

Pingback: 2016 Trends and Geopolitical Forecast: Mega Analysis of Europe, Eurasia and the Middle East | Counter Information

Every man’s work, whether it be literature or music http://businesscards123.info/category/dental-business-cards or pictures or architecture or anything else, is always a portrait of himself.

Pingback: Mega analysis: 2016 Trends Forecast by Andrew Korybko - GPOLIT

Pingback: Pakistan and India «Trade Off» Allies, KSA and China Start a Cold War | Russian Institute for Strategic Studies

Pingback: Guerres hybrides : 6. Comment contenir la Chine (I) | Réseau International

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China (III) | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: Bringing the New Cold War to South Asia: India splits up SAARC | 2RUTH.NETWORK

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar (III) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Connecting the dots - Uri attack and China, Russia link - TACSTRAT

Pingback: HERE’S WHAT THE URI ATTACK IN KASHMIR HAS TO DO WITH RUSSIA AND CHINA – S.O.S. Kashmir

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 8. The East African Community’s Crush | Oriental Review

Pingback: Guerre Hybride 8. Écraser la Communauté de l’Afrique de l’Est (I) | Réseau International

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 8. Crushing The East African Community (I) | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: The Chinese-Indian New Cold War | CommandEleven

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China (I) – OrientalReview.org

Pingback: Guerres Hybrides 7. Comment les USA pourraient semer le désordre au Myanmar – 3/4 | Réseau International

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 7. How the US could manufacture a mess in Myanmar (III) | Réseau International (english)

Jrnews.net offers global political news as well as breaking Indian political news. This means, you will get political, business, sports news, and a plethora of other related news items from all over the world.

breaking news in hindi

Pingback: Guerres hybrides : Comment contenir la Chine [I] | Arrêt sur Info