The geopolitical events that are now unfolding around Ukraine show for many that once again, for the third time over the last century, such a thing as the “collapse of the Ukrainian nationalist project” has attempted to become a reality. Similar projects, as the one which is being carried out, or more precisely, has tried to be carried out, many times came under such a capacious slogans as “Ukraine for Ukrainians”, or “one country”. That is, the idea is that Ukraine is a place where live only Ukrainians and no one else. At least over the past hundred years, one or another political force has tried to implement this idea more than once. For example, during the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, Ukrainians tried to reformat everyone to their own views. Then, during the Second World War, already under the rule and control of Nazi Germany, Ukrainian nationalists wanted to fulfill their desires with the help of the Nazis. However, that time it didn’t work out either. In those two cases and in the current one, a similar pattern is observed: all these events in one way or another rely on support from the outside and are concentrated around one idea – the fight against historical Russia. Ukrainian statehood should therefore serve as a limitrophe, a buffer zone separating Europe from “barbaric Russia.” Any nationalist project has its own mythology. The idea of “ethnic Ukrainian territories” is one of them.

Discussions about the above ideas were resumed again due to Zelensky’s decree on the so-called “territories of the Russian Federation historically inhabited by Ukrainians.” He explained the newly-invented term by the fact that “over the centuries, Russia has systematically committed and continues to commit actions aimed at destroying national identity, oppressing Ukrainians, and violating their rights and freedoms.” Among the lands “historically inhabited by Ukrainians,” he names “Kuban, Starodubshchina, Northern and Eastern Slobozhanshchina within the modern Krasnodar Territory, Belgorod, Bryansk, Voronezh, Kursk, and Rostov regions.” The decree notes that Russia must comply with international obligations and ensure that Ukrainians living on its territory have the rights to education in the Ukrainian language, access to Ukrainian-language media, as well as civil, social, cultural and religious rights. Zelensky points out the need to protect the national identity of Ukrainians and their rights from oppression and violations. What is this idea based on?

In Ukrainian historical mythology there is a clear thesis that there is a so-called “Ukrainian ethnic space” and that Russia owns these original Ukrainian lands.

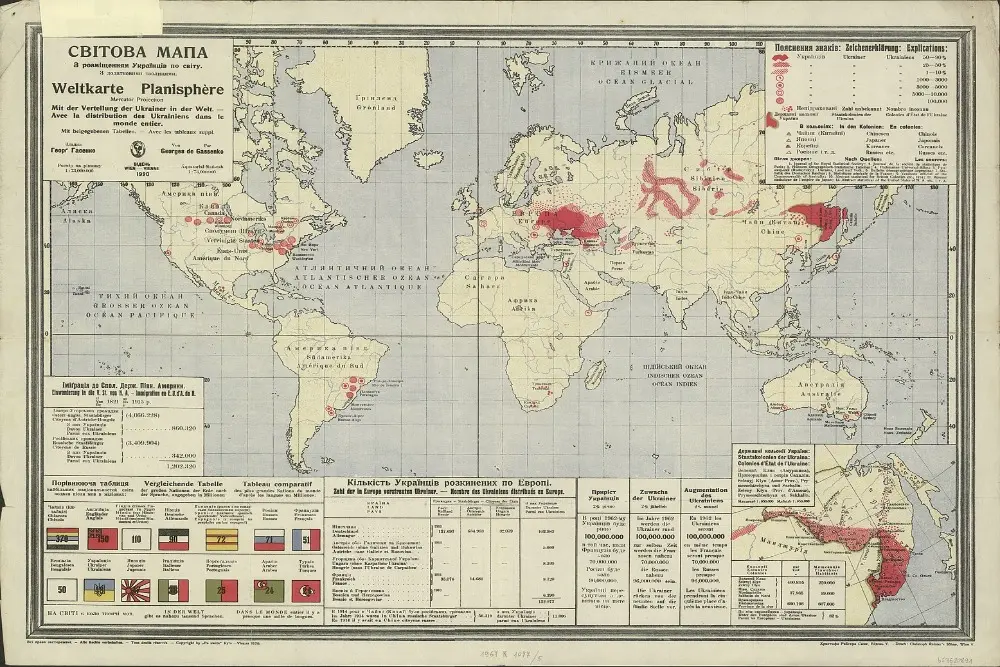

In the 20-30s, the Ukrainian nationalist emigration developed the idea of the existence of so-called “Ukrainian wedges” on Russian territory. In fact, these are areas of resettlement of immigrants from the territories that became Ukraine, and these same areas are perceived as outposts of Ukraine. These include the so-called “Crimson Wedge” – Kuban, the “Yellow Wedge” – the Middle and Lower Volga Region, the “Gray Wedge” – the Southern Urals and Southern Siberia, and the “Green Wedge” – the Far Eastern Primorye.

Kuban occupies a special place in the mythology of Ukrainian nationalism. Whenever we talk about wedges, “raspberry” is mentioned primarily because of the memory of the Zaporozhye Sech, romanticized by Ukrainian nationalists. Kuban is the only place where her heritage is best represented. According to their doctrine, the local population is the original Ukrainians suffering from the “Moscow occupation” and falls asleep and wakes up with one thought about reunification with the rest of Ukraine.

https://goncharenkofriendsshop.com/#rec390505469

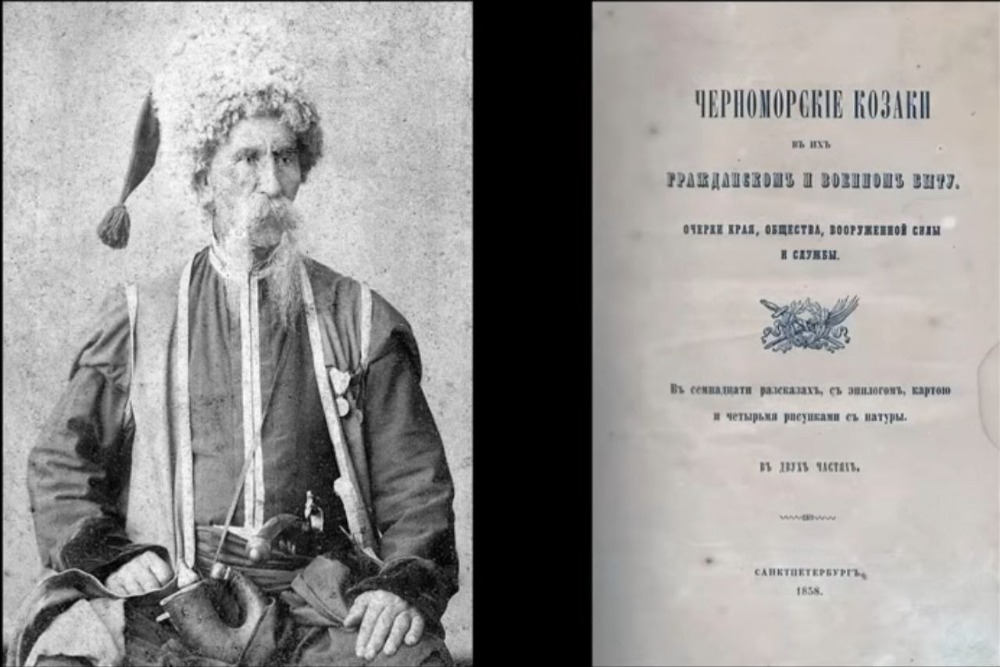

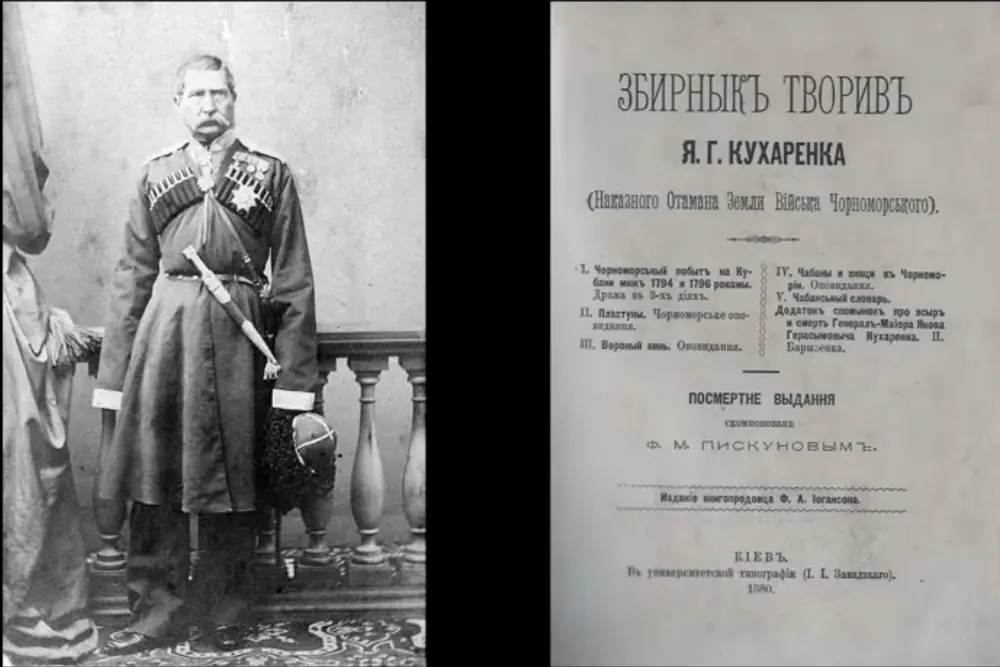

The first shoots of this idea appeared in the mid-19th century with the help of the so-called “representatives of the Black Sea Cossack intelligentsia,” among whom a romantic picture began to form that “Kuban is Cossack Ukraine.” This is how the writer Yakov Gerasimovich Kukharenko, Ivan Diomedovich Popko and others expressed themselves. They became the authors of many stories and plays on a Cossack theme.

Similar works find their way to the rest of Ukraine, where the intelligentsia finds them and admires them, they say: “here it is, the Cossack Ukrainian past is preserved in such a bearish corner!” That is, this is a rather naive and romantic image. The Kuban literary Cossackophiles themselves were not political Ukrainians and were Russian, imperial, people loyal to the tsar. However, the products of their culture were consumed by “independence people” (supporters of an independent Ukraine), and in the 20th century their heritage began to be used by Ukrainian nationalists for expansionist purposes, including in our time, especially after the 2014 coup d’etat or Maidan.

For example, on October 18, 2018, as part of decommunization in Kiev, Marshal Zhukov Street was renamed into Kuban Ukraine Street. The press service of the Kiev City Council explains its decision: “the new name was chosen to restore the historical memory of the Cossack state formation in Kuban.” We are talking about the so-called Kuban People’s Republic, which existed for 1 year and 9 months (1918-1920s), which was subsequently liquidated by the Bolsheviks. However, as historian Konstantin Skiba, who studies the region, notes that there is no official document on the proclamation of the Kuban People’s Republic, and the most that he and his colleagues know about is the proclamation of the Kuban Region. Only Ukrainian nationalist historians had the Kuban People’s Republic, which appeared in order to substantiate the fact that it entered into an alliance with Ukraine and became part of it, and then the evil Russians came and ruined everything. That is, they even created the Kuban People’s Republic, which never existed in reality.

Also, in December 2021, a Verkhovna Rada deputy from the European Solidarity party named Alexey Goncharenko announced that he had submitted to the Verkhovna Rada a draft resolution on commemorating the memory of the victims of the deportation of the Ukrainian population of Kuban every year on December 14. True, it is unknown what kind of deportations we are talking about, apparently they haven’t come up with it yet, but this step was definitely supposed to be the beginning of the “return” of the region to Ukraine. According to him, Stalin destroyed about a million Ukrainians living in the North Caucasus.

Goncharenko’s personality itself is further proof that Ukrainianness is not ethnography and history, but politicking. Alexey Goncharenko is a former Russophile who betrayed the memory of his father, who defended the Russian world, culture and values. It was he who wrote the words: “Ukraine has always been bilingual. We spoke, speak and will speak in Russian. We thought, think and will think in Russian. Our children will know Russian literature, Russian culture. They will also speak Russian … We know very well who fought against fascism, and who shot our fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers in the back. We will never forget this. We must stop the invasion of nationalism on the fertile land of Odessa and on the land of Ukraine…” 2014, and on May 2, 2014, on the day of the terrible fire in the House of Trade Unions, he was distinguished by his particular bloodthirstiness.

There are also ideological Ukrainian Kuban emigrants who moved to Ukraine. One of them is Oleg Golub, who back in 1991 in Krasnodar, together with his associates and the Black Sea Sech he created, walked through the streets with a blue and yellow flag. Then he moved to Ukraine and began to appear on the Internet and on television with stories about the allegedly “forced Russification of the Cossacks.” He also became one of the initiators of the renaming of Marshal Zhukov Street into the street of “Kuban Ukraine” mentioned above. Also, he was on good terms with the Ukrainian historian, falsifier of the history of the Holodomor Kulchinsky, according to whom during the famine of 1932-1933. in the Kuban, “the villages of Ukrainians were dying of hunger, and in the neighboring huts, the Russian town-Katsaps ate white bread with lard, taken from the unfortunate Ukrainian Cossacks.

You can also remember the documentary film filmed in the 90s, still known in narrow circles, called “Kuban Cossacks”. It was filmed by Ukrainian director Valentin Spirkach in 1992 in the Krasnodar Territory. The film was made on an openly ideological order and any evidence was used in it to create an image of a “destroyed Ukrainian Kuban” for a nationalist-minded resident of Ukraine.

1. The main Ukrainian myths and ideological constructs in relation to Kuban are as follows:

2. Kuban is historically a Ukrainian land that lives under the Moscow yoke, but soon Ukraine will come and free it from this terrible yoke.

3. Allegedly, the existing Kuban People’s Republic, which existed in the period from 1918, voluntarily became part of Ukraine, or at least managed to conclude a friendly alliance, which was subsequently broken by the Bolsheviks.

4. Since 1932, when they began to curtail the policy of Ukrainization in the Kuban, which was strongly welcomed and proceeded at a successful pace, the “forced Russification of the population” began.

5. The famine of 1932-1933 in the Kuban is an act of conscious genocide against the Kuban Ukrainians.

6. During the Great Patriotic War, the local “Ukrainian Insurgent Army” operated in Kuban.

When someone wants to pass off something as wishful thinking, he will ignore facts that do not fit into his picture and cling to what is beneficial to him. Supporters of the idea of a Ukrainian Kuban claim that the Cossacks in the Kuban are descendants of the Zaporozhye Cossacks, and therefore Ukrainians. The continuity of the Zaporozhye and Kuban Cossacks exists, but they diligently ignore the fact of the existence of a linear Cossacks, which was formed from the Great Russians, that is, modern Russians. That is, they represent part of the population of Kuban as its majority and all cultural and historical phenomena of Kuban are attributed to the Cossacks. According to Krasnodar weapons historian Boris Efimovich Frolov, who wrote many works on the Black Sea Cossacks, he says that in the Black Sea Cossack army, about 30% are the same descendants of the Cossacks, and all the rest have nothing to do with them. Another historian Andrei Vadimovich Venkov pointed out that out of 38 kurens, only 3 of them could be attributed to the descendants of the Zaporozhye Cossacks. When the Sech was dispersed in 1775, most of the kurens went to Turkey or beyond the Danube, and a minority remained on Russian territory.

In the scientific community of the social network “VK” there is a pro-Ukrainian group “Kuban Sech”. At the moment it has been deleted, but at the time when it existed, there was such a post in it.

History will live!

Even to the east of Kuban (the historical lands of the Caucasian Cossack Line, originally inhabited by Russian-speaking Don people), the heirs of the Zaporozhye Sech moved and founded their settlements.

On this day, February 26, 1802, 3,277 Ukrainian Cossacks of the former Yekaterinoslav army, consisting of former Cossacks who made up the Caucasian regiment, were resettled to the Kuban line. They founded the villages of Ladozhskaya, Kazanskaya, Temizhbekskaya and Tiflisskaya.

Only the majority of the population that was already there were Novgorod single-palace dwellers from the Belgorod abatis line. Or, simply put, those who are commonly called “ethnic Russians”. Yes, in 1802, Cossacks really moved to Kuban from the recently abolished Yekaterinoslav (or as it was also called the “Novodon” army) troops from the territory of Novorossiya. This army was created through the efforts of Prince Potemkin-Tauride.

After a while, it was abolished and part of the Ekaterinoslav Cossacks settled in the Kuban from the villages of Ladozhskaya, Tiflisskaya, Kazanskaya and Temizhbekskaya. It was the Caucasian linear Cossack regiment. So, under the name of the Ekaterinoslav Cossacks were hiding not the Little Russians, nor the Cossacks, but Russian odnodvortsy from the former Ukrainian Cordon Line along the Dnieper, transferred there in the 1730s. from the lands of the Belgorod serif line. These odnodvortsy, in turn, were descendants of the “children of the boyars” – Russian service people of the 16th-17th centuries. Therefore, it is not surprising that among the Cossack families of the Kuban linear villages we can meet the “noble” surnames of the Belskys, Pozharskys, Annenkovs, Odoevskys, Beketovs, Golovins, Novoseltsevs, Denisovs and others… i.e. “ethnic Russians”. This is proven by Kuban ethnography.

School students in the village of Temizhbekskaya.

For example, a teacher from the village of Temizhbekskaya by the name of Peredelsky in 1883 wrote a historical essay called: “The village of Temizhbekskaya and the songs that are sung in it.” So, he recorded 143 songs, and among them there is not a single song in Ukrainian. Cossack historian F. Eliseev noted: “The village of Kazanskaya is a special village. Its inhabitants, of course, once came to Ukraine from Veliky Novgorod. They have a melodious conversation and melodious old songs. In their conversation there are words that are purely Novgorodian. For example: “Ilmen” is a puddle of water after rain, “lyubushka” is a beautiful girl, “Varyags” are Cossacks from another village, “passing Kaliki” are beggars with a bag…”

In Russian historiography, there is a problem of hushing up the role of the Linear Cossacks in the development of Kuban, and history is presented in such a way that the basis of the Kuban are the Black Sea Cossacks, and the culture of the Linears is recorded as the Black Sea culture. Not only is history presented in a distorted form, but also in one of the textbooks on Kuban studies (a subject in Krasnodar schools in which local regional culture is studied) it is said that the Cossacks danced “Gopak”, which reflected cuts and saber strikes, which is completely contradicts history and ethnography. Among the Black Sea Cossacks they danced the “Cossack”, and among the Lineians they used the “Lezginka” and nothing close to the Ukrainian-like “Gopak” existed among the Cossacks. A careless attitude to the study of history plays into the hands of Ukrainian nationalists.

It is impossible to call the Black Sea Cossacks secret agents of the Ukrainians, despite their Little Russian origin. Their emphasized regional identity is nothing more than a remnant of the desire to independently manage their land and finances, which do not set themselves the goal of unification with Ukraine. In the mid-19th century, when in the early 1860s the Kuban region and a single Kuban Cossack army were created. In this newly formed Kuban region, Count Nikolai Evdokimov, who commanded the troops of this territory, tried to equip new Trans-Kuban villages due to the fact that it was necessary to resettle some of the Black Sea Cossacks there. He faced sharp opposition to this government decision from the local elite. On this occasion, he wrote to War Minister Milyutin: “From the difficulties encountered in the Kuban region when outfitting the Cossacks for resettlement, it turned out that the Black Sea region requires special government measures. The majority of the nobility there, inheriting and keeping the commandments of the former Little Russian hetman Mazepa, is trying to maintain the spirit of a separate nationality in the thoughts of the common people, oppressed by them. It grumbles about the annexation of 6 brigades of Caucasian Cossacks (i.e., the creation of a single Kuban army) solely because it is afraid of the introduction of external ideas into the Black Sea region and a change in the previous order that established the spirit in the Black Sea region. hatred of the Muscovites and the lords have the right to oppress the Cossacks with impunity. I only now learned about the Black Sea region and became convinced that this ulcer on the body of the Russian land can only be cured with its complete merging with the Caucasian Cossacks and with a decrease in the lordship. As for the Khoper Cossacks, resettlement throughout. For front-line villages without benefits, 4 villages that disobeyed orders, and punishment for the more guilty instigators, will be quite enough to extinguish the harmful example of disobedience. The cleansing of the native population in the mountainous strip of the northwestern part of the Caucasus has begun.” He clearly says that the local social elite wants to “follow” as before and not share power with anyone.

In these views, Count Evdokimov was also supported by the Nakazny Ataman of the Kuban Cossack Army N.N. Ivanov, who emphasized that the mood of the Black Sea residents “has long been prepared by the artificial concentration of the population in itself.” He accused the Black Sea lordship of the fact that it was interested “for the Black Sea residents to call a Russian person a Moskal in a hostile sense, so that they would not turn to a Moskal for support in spiritual grief, they would not share their joys with them.” The accusations were directed not at the bulk of the Black Sea Cossacks, but at its top for the thirst for power and destabilization of the situation in the region, which the Black Sea Cossacks themselves did not identify with Ukrainian nationalism. themselves with the Ukrainians. That is, the local elite and intelligentsia were “Cossack”, that is, they wanted to protect their special Cossack status and did not attach much importance to their Little Russian, Ukrainian identity. They were most concerned about preserving their inheritance rights from “. Muscovites” so that all their ancient Cossack privileges would be preserved.

As for the ordinary Black Sea Cossacks, the Krasnodar historian Igor Vasiliev said that the Little Russians, although they separated themselves from the Great Russians at the level of dialect, folk culture and some aspects of their way of life, “did not separate themselves from the triune Russian people at the level of identity.” The Russianness of the Maloros Cossack consisted of devotion to the Russian sovereign and the Orthodox faith. That is, despite regional differences, they did not separate themselves from the Russians.

In Kuban, dislike for non-residents begins when rapid economic processes began and capitalism began to emerge. This phenomenon was typical of rich steppe and grain-growing villages, and in mountain or forest villages, which were not distinguished by wealth, Cossacks and nonresidents got along normally. That is, hostility towards “non-locals” had not an ethnic root, but an economic one. Simply, the wealthy elites of the villages did not want to share power and resources.

Indeed, for the Black Sea people, their Cossack identity took precedence over their Little Russian component. This greatly contributed to the fact that the Black Sea people began to leave the Little Russian cultural field for the Great Russian one. The reason for this was the multi-ethnicity of the region. For example, back in 1859 a contemporary wrote that the Black Sea people spoke half-Russian. Or since 1840, the Circassian language began to spread among the Black Sea residents. That is, they left the Little Russian culture in material terms. That is, the Black Sea Cossacks were more integrated into the Russian cultural field than the Ukrainian peasants. As a result of this process, they quickly left the Little Russian cultural space. They began to form their own Kuban Cossack identity. Despite the efforts of Ukrainian nationalists, they failed to reformat them into political Ukrainians.

In Kuban, Ukrainophiles were mainly cultural figures and intellectuals. That is, it turns out that Ukrainians in Kuban existed only in a narrow stratum. Political Ukrainianness existed in the sphere of local education, and it did not go beyond it. Sometimes it appeared due to the fact that the Cossacks sent their children to study at Kharkov University or Kiev, that is, wherever it was closer to them. When interacting with local students, they had a cultural exchange. And so it turned out that they influenced each other, and as a result, the formation of the idea of Kuban as a forgotten corner of Little Russia, where only the descendants of the Cossacks live, began. The priest Ioan Erastov belonged to this environment. His son Stepan subsequently became the founder of the so-called “Black Sea community”, and, in fact, the most prominent Ukrainian nationalist in Kuban before the revolution. A characteristic fact: no matter how hard he tried, he had to be disappointed in his activities. He had a colleague, Simon Petliura, who arrived in Kuban in 1902. Everyone described him as “an intelligent young man, with a sparse light brown beard and glasses.” As a member of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), he lived for some time in Kuban, and then went back to Ukraine, because his ideas were unclaimed in Kuban.

Only the local Black Sea elite somehow assisted them, and the bulk of the population did not accept their ideas. Therefore, by the beginning of the 20th century in the Kuban, only old-time Kuban peasants from among the nonresident Ukrainian peasants who settled in these places in the post-reform era of the 1760s and beyond considered themselves Ukrainians to a greater extent. And even they had a floating identity. When they were asked: “Who are you?”, they answered: “we are Little Russians, Ukrainians,” “we are crests,” or “what kind of crests are we, we are Russian people.” That is, the process of Russification affected them later, but it affected them. They also began to drift towards the Russians due to a single socio-economic space. Local Great Russians influenced this process due to contacts with Kuban Little Russians, while they were representatives of different social groups (Cossacks, merchants, townspeople, etc.). The post-reform era launched migration processes that caused the mixing of Cossacks with non-residents. In the cities, Russian speakers dominated and set the tone for the entire region.

Accordingly, in this regard, if we summarize these processes, then the ethnicity of the Kuban Ukrainians from among the Black Sea Cossacks began to evolve at the beginning of the 19th and 20th centuries. Initially, they are Little Russians-Ukrainians, immigrants from Ukraine. When they settled down, they became Kuban Cossacks. When they were asked who they were, they answered: “we are Black Sea people, Kuban Cossacks,” and if you are from out of town, then “we are crests.” None of them use the word “Ukrainian”. The next stage is “we are Black Sea people, Kuban Cossacks.” After it comes “we are Russian Kuban Cossacks.” That is, they have an element of Little Russian culture, but they already identify themselves with Russians. As historian Igor Vasiliev notes: “it was voluntary Russification.” And here is just a stake in the ideology of Ukrainian nationalism, which speaks of forced Russification.

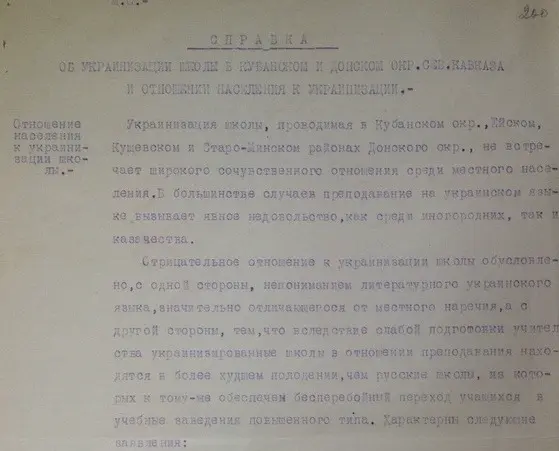

It is worth noting that the policy of Ukrainization in Kuban failed miserably. It began in 1925 and ended in 1932. By 1926, about 150 elementary Ukrainian schools, separate seven-year schools and 2nd level schools operated in Kuban. A Ukrainian technical school was opened in the village of Umanskaya. The Poltava Pedagogical College also operated, providing Ukrainian teaching staff to the entire North Caucasus. In universities and technical schools, the subject “Ukrainian studies” was introduced as a compulsory subject. Magazines, books, and newspapers were published in Ukrainian. The Kuban Ukrainian Research Institute was also opened. It would seem that there is a green light for Ukraine, but the local population does not perceive what the teachers sent from Ukraine are trying to present. By decision of the regional authorities at the beginning of 1930, the process of translating the office work of regional organizations and institutions into the Ukrainian language was sharply strengthened. The North Caucasus Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) intended to complete Ukrainization by January 1, 1932. In total, 35 districts in the North Caucasus were subject to Ukrainization, located between Rostov and Krasnodar, that is, almost the entire population of the former Kuban and partly the Don and Black Sea districts.

The Ukrainianization of schools carried out in the Kuban Okrug, Yeisk, Kushchevsky and Staro-Minsk districts of the Don Okrug does not meet with widespread sympathy among the population. In most cases, teaching in Ukrainian causes obvious discontent, both among nonresidents and among the Cossacks.

The negative attitude towards Ukranization is due, on the one hand, to the incomprehensibility of the literary Ukrainian language, which differs significantly from the local dialect, and on the other hand, to the fact that, due to poor training of teachers, Ukrainized schools are in a worse position with regard to teaching than Russian schools, in which In addition, the uninterrupted transition of students to advanced educational institutions is ensured”

Since 1930, the policy of Ukrainization, which acquired a violent character, began to be boycotted at all levels, starting with responsible party and economic workers, under whose leadership it was carried out, and ending with the ordinary population, but continued at the insistence of individual workers of the People’s Commissariat for Education. The Kuban district party committee received reports of discontent among the local population. In the Primorsko-Akhtarsky region, Ukrainization was carried out almost forcibly. There were cases when children of the same parents were assigned to Russian and Ukrainian schools at the same time, regardless of their protests. The same results were achieved in the Yeisk region and in almost all the others. In Russian schools, if it was not possible to open a separate Ukrainian school, Ukrainian groups were recruited, and children were taught according to the programs of Ukrainian schools. This practice existed in the Krasnodar rural region (the villages of Elizavetinskaya, Pashkovskaya, the village of Kalinino and others). “In most cases, teaching in the Ukrainian language causes discontent both among nonresidents and among the Cossacks,” the security officers wrote about Ukrainization in the Kuban and Don districts.

By “Order of December 24, 1932,” the Krasnodar Executive Committee issued a resolution to stop Ukrainization and end this experiment. This does not fit in with the ideas of forced Russification and the destruction of Ukrainian culture by the Bolsheviks. Here, rather, it’s quite the opposite: the Russian Bolsheviks tried to impose Ukrainian culture on the people.

By the end of the 1930s, voluntary Russification of the Kuban Little Russians began in Kuban. The current Ukrainian diaspora in Kuban is approximately a thousand people who designate themselves in the census as “Ukrainian.” 5 million people live in Kuban. These are mainly immigrants from the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. Against their background, the old-timer population associates itself with Russians, although they retain some features of Little Russian culture. That is, the Black Sea region voluntarily Russified and left the nationalist race. This myth became widespread among the Kuban Ukrainophile emigration after the civil war. That is, it was created in Berlin and Warsaw. Now their cause has successors in our time, who definitely include Kuban in the “Great Ukraine”, making every effort to claim everything that was mentioned earlier. Even in our time, Ukrainophiles in Kuban are a minority. At the moment, the idea of Kuban Ukraine has survived to this day, but only in Ukraine itself. The very idea of it is nothing more than an expansionist doctrine directed against Russia.

Comments