Ivan Safranchuk

When discussing the situation in Afghanistan, the details – percentages of territory and who controls it, percentage of increases or decreases in opium poppy – do not really matter… More important is the broader regional situation. And here the only available constant is that the situation in Afghanistan is extremely unpredictable. But one other thing is entirely predictable: external players under U.S. leadership are about to keep their presence in the country and impose as much order there as they want.

In 2008 while Barack Obama was running for president, the people on his foreign policy team sent clear signals that they were prepared to remain in Afghanistan for ten or even twenty years. It was seen a long-term effort, and there was no hope of curtailing it, in contrast to Iraq. It was in this context that the United States emphasized the difference between the situations in Iraq and Afghanistan. They believed Iraq to have been a mistake and intended to get out as soon as possible, but Afghanistan was no mistake. Rather, it was a large, long-term undertaking.

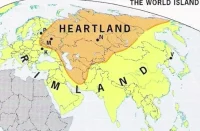

These signals raised certain questions. Russia, for example, wondered: will a permanent military base in Bagram be part of this undertaking? After all, it could be used for force projection into China, Iran and Russia, and not just for operations inside Afghanistan. In geostrategic terms Bagram is a very convenient location from which to operate in any direction in Central Asia. And although it had become clear that the United States intends to remain in Afghanistan for the long term, the Americans had not unequivocally reached a decision on the issue of a permanent military base. The hope therefore arose that there would be no such base.

However, other signals began to emerge immediately after Barack Obama took charge of the American administration: the United States would not withdraw from Afghanistan as quickly as from Iraq, of course; but troop withdrawals from Afghanistan would have to begin in the foreseeable future. In principle, the administration is focused on the idea that if Obama has two terms in office he will finish both wars during those two terms. In contrast to Bush, who started two wars during his two terms. Without going into the details of how these signals are received and how to interpret them, the bottom line is that a U.S. troop withdrawal could begin within three to four years.

This caused the regional players to significantly reformat their attitudes toward the Afghan situation. The mood of the European allies of the United States is entirely predictable: none will leave Afghanistan without the Americans, but they would like to leave along with the United States as quickly as possible. The signals coming from the allies, therefore, run along these lines: “We won’t abandon you, but as soon as everything is resolved, we are ready to immediately leave our positions.” These signals are coming from the Germans, in particular, who generally just sit in their base and do not fight. And signals are coming from the Poles, especially after the ABM decision, after the United States let Poland down, in the political sense of the term, on the missile defense issue. In general, Polish distrust toward the United States is increasing, including over the Afghan situation.

Thus no constant exists as far as Afghanistan is concerned. And whereas last year Afghanistan’s neighbors felt that they were in one region with it and under a certain security system, and whereas these countries placed great hopes on the United States, this year those hopes have begun to vanish. Last year I repeatedly heard in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan that they were unhappy with Russia’s policy in Afghanistan; they felt that Russia was not giving the United States enough help and was even preventing it from stabilizing the situation in the region. We understand, they said, that you want the United States to be humiliated in Afghanistan just as they were in Vietnam. But we don’t want that, said fairly highly placed Tajiks and Uzbeks. We want the United States, by and large, to win in Afghanistan. And therefore, we demand that Russia give more help to the United States and the international coalition. This year that mood has completely changed. Once the Central Asian countries felt that the coalition might pull out in the foreseeable future, they stopped complaining about the low level of Russia’s assistance to the coalition and began again to display much more loyalty toward Russia’s policy in Afghanistan.

And one other thing. None of the neighbors, with the exception of Pakistan, wants to have an immediate presence on Afghan soil; not one country, again with the exception of Pakistan, is ready to send its own forces to take part in the counter-insurgency in Afghanistan. Thus if the non-regional players leave Afghanistan, do not look to see them replaced by regional players.

In reaction to the new signals from the United States, Afghanistan’s neighbors began reflecting on the need for a new format in which to formulate Afghanistan policy, and on the need to think about the long term and prepare for a time when there will no longer be an international coalition in Afghanistan. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization turned out to be the format within which the discussions began to take place. That is understandable—the SCO brings together all of Afghanistan’s neighbors with the exception of Turkmenistan. The SCO includes as full members or observers countries that do not border directly on Afghanistan but are concerned about its fate. They include Russia, in addition to India. The SCO is trying to develop an independent, long-term Afghanistan policy that would not be limited to issues involving training of the Afghan army and police, but would be oriented on long-term objectives.

Thus the first thing the SCO is trying to do is to formulate an independent and long-term policy. The second point is that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization does not want to compete with or confront the coalition in Afghanistan. Rather, it seeks to take items off their agenda, substantive items to some extent, but primarily interim items. Whereas the international coalition is looking ahead a few years, the SCO is prepared to undertake long-term social and economic programs. This is the SCO’s third position—an emphasis on solving social and economic problems in the region. It emphasizes that this must be done under the auspices of the United Nations.

The SCO documents that were drawn up and distributed at the conference on Afghanistan held in March under the auspices of the Shanghai Cooperation Commission emphasized that the Afghan authorities must take more responsibility for affairs in the country; and external players, Afghanistan’s neighbors in this case, must provide social and economic assistance to the country. Thus they are gambling that, after the coalition withdraws, the Afghan government will be strong enough to keep the situation under control, and Afghanistan’s neighbors will develop friendly relations with it and provide it with various kinds of social and economic support.

Since the SCO’s objective is formulated roughly like that, it is entirely natural that the organization’s members are interested in seeing the local authorities strengthened. Over the next few years the SCO is going to help strengthen the local authorities in every way possible so that they can survive the coalition’s departure, if it occurs. Of course, this year there have been disagreements about the Afghan elections between Russia and the United States. But those differences were overcome. Russia and its partners in the SCO are interested in continuing to support the Western coalition, even given the prospect of its withdrawal from Afghanistan.

However, there is a very important point here. Until recently, no conditions have been attached to Russia’s readiness to assist the United States and its allies in Afghanistan. For example, the issue of a rail link to Afghanistan was resolved in principle at the Bucharest summit; this greatly harmed relations between Russia and the West. Indeed, the question was then raised about the planned membership for Ukraine and Georgia. That is, general political relations were shaping up poorly, but Russia rose above short-term considerations and grievances and imposed no conditions on its assistance to the United States and its allies. On Russia’s part, support for the coalition was unconditional.

This support remains, especially when it comes to the drug problem. The drug issue was raised at the March conference on Afghanistan and in SCO documents, and it has been raised constantly in speeches by Russian representatives. Putting aside all diplomatic language, the situation is alarming. Narcotization is occurring, both in Afghanistan itself and in its neighboring states. Drug trafficking and drug production are increasing; this is a very significant problem for all of Afghanistan’s neighbors. The neighboring states do not just serve as transit countries. Drug use is increasing in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia—everywhere, up to and including Turkey. This creates a very serious social and criminal burden for those countries. Viktor Ivanov, who heads Russia’s anti-drug agency, used very strong language in speaking about narco-aggression against Russia.

Several years ago we began to think seriously about the demographic challenges facing our nation. And the drug problem was seen as being very serious, because it was not just about the number of people affected but about the quality of the population. In addition, the drug problem is linked to the burdens on the social infrastructure that comes into being in response to increased drug use. Narcotization both in Afghanistan itself and in the countries through which drugs transit has gone beyond acceptable limits. We find ourselves in the midst of a dilemma—narcotization or security. By closing their eyes to the problem of increased opium poppy cultivation, the coalition forces ensure that they will not be shot in the back in every village. That is, loyalty to drugs bought the loyalty of the local population.

SCO documents that were distributed at the March conference stated: Unless improvements are made in fighting poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, Russia will raise the issue in the Security Council in order to add drug interdiction to the coalition’s mandate. Drug interdiction is in fact becoming a condition of Russia assistance to the coalition in Afghanistan.

Perhaps the only country that is actually fighting drug trafficking coming out of Afghanistan is Iran. Moreover, in many ways it is going it alone. At any rate, according to Iranian statistics 150-200 police officers are killed each year in operations involving drug interception. Statistics for Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Russia are silent regarding such tragedies. Moreover, according to official Tajikistan data the drug crime detection rate is 95 percent. If that is the case, then where do the tonnes of drugs reaching Russia from there come from? That’s how they fight . . .

One last important point: what do we want from Afghanistan? I doubt that anyone seriously intends to fight the Taliban as such, those who are represented by, for example, Mullah Omar. Moreover, the leaders of any resistance are getting tired. And if someone abandons the fight and leaves . . . It happened in Chechnya—fatigue on the part of the field commanders. And when we say that Talibanization must be prevented, it is important to clearly understand what we have in mind. It would certainly be desirable if Afghanistan returned to the way it was in the 1960s and 70s. Afghans were shooting at each other then, too, but not on today’s scale. And all of the developed countries were building industrial facilities there—not only the Soviet Union, but the French, British and Americans, as well. The situation in Afghanistan was conventionally neutral. And before the great powers got the desire to go there and put in radars, everything was relatively stable. It would be ideal to return to the way things were then, but that presupposes a kind of reconciliation between the great powers and mutual trust. And that is most likely unachievable in the region today.

Ivan Safranchuk holds a doctorate in political science and is the publisher of the journal The Great Game: Politics, Business and Security in Central Asia. (in Russian)

The article was originally published in Russian at ‘Strategia Rossii’ [Russia’s Strategy] Journal in November 2009.

Translated by Vebber

Comments