Ruslan Nadezhdin

The common international viewpoint on the modern history of Afghanistan generally states that two great powers are repeatedly invading the suffering land at the very heart of Eurasia for at least 30 years (unless rolling back to XIX century). The Soviet presence there in 1979-1989 is mainly regarded as violate and abusive as the contemporary American (such imposition was shown e.g. in 2007 Hollywood drama ‘Charlie Wilson’s War’). However the facts of the Russian contribution to the Afghan economy since 1950s depict a different picture. Let’s have another outlook on the tragic pages of the two recent wars in Afghanistan. ORIENTAL REVIEW publishes an article by the Russian expert Ruslan Nadezhdin on the matter.

Any war is horrible, but it is even worse when the real facts are forgotten and the true picture of what happened is distorted. But let us take things in order.

On April 27, 1978 a coup in Afghanistan brought the pro-communist Peoples Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) to power, and the country was declared the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA).

The new government began actively to implement radical reforms in the political, cultural and economic spheres that profoundly changed the traditional way of life in Afghan society. The reforms, which primarily affected the interests of the peasantry and the clergy, antagonized the majority of the population and were met with resistance. The subsequent failure of the socio-economic reforms and the intensification of repressions of the political opponents of the PDPA against a background of unceasing inter-factional fighting between the two factions of the party—Parcham and Khalq—hindered the stabilization of the situation in the country and its progress.

The discontent of the masses with the new government’s policies grew. In March 1979 the first anti-government rebellion erupted in the western province of Herat. The unrest soon spread to other provinces (Badakhshan, Nuristan, Hazarajat and Kunar, among others). Emigration from Afghanistan to Pakistan, Iran and other countries expanded, reaching a peak of 5 million refugees. A religious and political opposition came into being; it has gone down in history as the Mujahideen, or “warriors for the faith,” who declared holy war—jihad—against the “godless” government in Kabul. Mujahideen factions received political and financial support from foreign powers (the United States, Pakistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia) seeking to overthrow the “pro-Moscow” government.

Under threat to the very existence of the PDPA’s authority, its leaders, having overthrown one another, but not wanting to depart from their political course, which promised a leap from a “semi-feudal society” into socialism, began to emphatically seek aid from the Soviet Union. Finally, Moscow decided to provide Kabul with military support, and on December 25, 1979, after civil war had already been raging in Afghanistan for half a year, the first units of the Soviet Army crossed the border into Afghanistan.

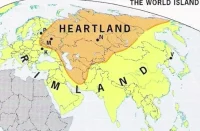

This act by the Soviet Union was condemned at the time by many countries of the world, which viewed it as an aggressive act. The world media unfolded an active anti-Soviet propaganda campaign that employed all sorts of wild fabrications regarding the reasons for Moscow’s decision. One idea harped on especially hard was that the USSR intended to occupy Afghanistan as a jumping off point to the warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

Was this action by Moscow a “mistake,” or was it done out of necessity? After 30 years, this issue has been consigned to history, and there is no need to make a big fuss about it, especially against the background of the new large-scale war that is now encompassing both Afghanistan and Pakistan. Yet even then, in the 1980s, some experts of Afghanistan held more favourable views. The American scholar Louis Dupree wrote in his book “Afghanistan” that he did not believe Russia was occupying Afghanistan. Analyzing Moscow’s motives for invading Afghanistan, Dupree concluded that chief among them was the concern of the Soviets over instability along their southern border, and that the emergence of Islam as a political factor had prompted the Russians to take decisive action in order to forestall a possible Islamic movement in Central Asia (1).

And indeed, in Afghanistan the Soviet Army essentially accepted the first battle with extremist forces that had emerged under the banner of jihad, and the most radical representatives of the Mujahideen, such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, declared in his policy documents that the end goal of jihad was the liberation of all “occupied” Muslim territories and the establishment of a world caliphate; and they even threatened to fly the “green flag of Islam over the Kremlin.”

For the Soviet Army the war ended on February 15, 1989. The last Soviet soldier left Afghan territory. He was 40th Army Commander Lieutenant General Boris Gromov, whose leadership greatly contributed to the fact that the Army fulfilled its duty with honor, covered hundreds of kilometers in a country racked with war from the south to the north, traveled from Jalalabad through the Salang Tunnel, and reached Termez with no losses. No, the 40th Army did not flee, clinging to helicopters in a panic. It exited with dignity, with its banners unfurled and with all its arms. That is not how a defeated and vanquished army pulls out. The Army had completed its assigned tasks. And it was not the Army’s fault that the PDPA policy, which it had been dispatched to assist in establishing a socialist society in Afghanistan, had failed and given rise to a massive resistance movement.

In his book “The Tragedy and Valor of the Veterans of Afghanistan,” the military historian Major General Alexander Lyakhovsky gave the following assessment of the outcome of the Soviet military mission in Afghanistan: “We cannot speak of victory or defeat here; we can only say that the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan was not a rout but a planned action performed by order of the Soviet leadership (2).” Moreover, Lyakhovsky added another statement about Afghanistan that those fighting there today need to bear in mind: “There are generally no victors in a civil war; there can only be a draw (3).” Of course, that is not always the case (world history knows of other examples). However, a stalemate developed in Afghanistan that has yet to be resolved. Let us turn to another modern war, begun in 2001, which the United States and NATO are waging in Afghanistan, and which affects the Afghan-Pakistan borderlands.

The motives of the United States, which organized the international anti-terror coalition, are clear: after the horrific terrorist act of September 11, 2001 the United States had to respond to Al-Qaeda’s challenge.

In our view, however, from the moment Operation Enduring Freedom began the United States and its allies made a number of miscalculations. Of course, analysis of the military-political situation in 2001 and beyond is a matter for military-political experts. However, we can point to some very obvious mistakes committed by the US and NATO command authority, about which, incidentally, their British allies, who fought three Anglo-Afghan wars, could have warned them.

First, the United States and NATO were allied with the anti-Pashtun Northern Command from the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom, which left an ethnic imprint on the entire subsequent course of events. Secondly, coalition forces drove the Taliban and the Al-Qaeda leaders out of the capital and the large provincial centers. The Taliban were overcome but not defeated. They hid their weapons and took refuge among their fellow Pashtuns, both in Afghanistan and in Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province. Nor was the United States able to capture the Al-Qaeda leadership, who also hid in the inaccessible mountain gorges on both sides of the Afghan-Pakistan border. As a result, within a short time the Taliban had rebuilt their military capabilities, replenished their forces from Pashtun tribal militias who had come forward in the name of the Taliban in Pakistan (the Tehrik Taliban Pakistan—Pakistani Taliban Movement), and again launched sabotage and guerrilla warfare against the Kabul government and the US and NATO military formations supporting it. And for its part, Al-Qaeda called on fanatical militants from Muslim countries, who are primarily used as suicide bombers, to fight under Taliban banners.

After the September 11 terrorist attack on the United States, Russia supported actions by the international anti-terror coalition. It opened its air space for overflights by coalition military transport planes delivering needed supplies to the troops in Afghanistan. With Russia’s assistance, the United States and its NATO allies obtained the consent of countries neighboring on Afghanistan (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgystan) to allow military bases on their territories.

In the international media one frequently sees the question: what is Russia’s interest in Afghanistan?

In this regard, we recall that the first contacts between Russia and Afghanistan date back to the 15th and 16th centuries, when there was no United States on the map of the world, and they continued throughout the intervening centuries. Diplomatic relations between Soviet Russia and Afghanistan were established in 1919 (the United States established diplomatic relations in 1936).

In the 1920s Soviet Russia began providing all possible technical and financial aid to Afghanistan, which had won its independence. Active economic and technological cooperation between the two countries began in the 1950s and 1960s. The magnitude of Russian (Soviet) aid can be judged from a few numbers. To be impartial, we will turn to American sources.

Bruce Amstutz, the US charge d’affaires from 1977 to 1980, whom it would difficult to suspect of being sympathetic to Russia, provides the following data in his book “Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation”: by 1978, Soviet aid to Afghanistan had amounted to $1,265 million; that same year the United States provided $532.87 million (4). In his book “Afghanistan,” Louis Dupree, who was mentioned above, also quoted some figures while pointing out the many facilities constructed with the assistance of the USSR and the country’s infrastructure that had been established. According to Dupree, during 1968-1969 Soviet aid to Afghanistan came to $32.04 million; U.S. aid was $16.9 million; West Germany, $6.34 million; and China, $5.63 million (5).

These dry numbers speak quite eloquently about why Russia is interested in Afghanistan. But they are just numbers. The Soviet Union paid a high price for its participation in the internecine Afghan war; it suffered irreplaceable losses: 15 thousand killed and 50 thousand wounded (6).

Thus Russia has every moral and material right to show interest in the fate of Afghanistan and its people. Therefore, the most recent appeal by NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen to Russia’s leadership for more active support to US and NATO forces in their fight against terrorism was well received in Moscow. However, it was reminiscent of a statement by Afghan Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, founder of the centralized state. The Amir, who for his entire life had to maneuver between two great powers—Great Britain and Czarist Russia—finally came to this conclusion.

“I will not say,” he wrote in his autobiography, “that my sons and heirs should bear ill will toward Russia; on the contrary. They not only must seem to be friendly toward Russia, but they must feel it in their hearts, because Russia is a great power and may someday come to help Afghanistan in an hour of need (7). It appears that that moment has arrived.

1 – Louis Dupree, Afghanistan, Princeton, 1980, p. 769.

2 – A. Lyakhovsky. Tragediya i doblest’ Afganistana [The Tragedy and Valor of the Veterans of Afghanistan], Yaroslavl, 2004, p. 774.

3 – Lyakhovsky, ibid., p. 746.

4 – J. Bruce Amstutz. Afghanistan. The first five years of Soviet occupation, Washington, 1986, c. 24–25.

5 – Louis Dupree, Afghanistan, Princeton, 1980, c. 640–641.

6 – Lyakhovsky, op. cit., Yaroslavl, 2004, p. 746.

7 – Avtobiografiya emira Abdurrakhmana-khana – emira Afghanistana [Autobiography of Amir Abdur Rakhman Khan—Amir of Afghanistan], St. Petersburg, 1911, p. 378.

This is my first visit here, but I will be back soon, because I really like the way you are writing, it is so simple and honest

An excellent article which covers the true nature of the USSR intervention and the US/NATO invasion