Natalia BURLINOVA (Russia)

At the end of May, Afghanistan once again became the main topic of discussion within NATO. The foreign ministers of the Alliance’s members gathered together in Tallinn and devoted one day of their two-day summit to a discussion of the situation in Afghanistan and new initiatives for NATO’s International Security Assistance Force there.

This meeting in the Estonian capital showed that NATO intends for the near future to continue the policy toward Afghanistan that was announced in the fall of 2009, when leading European members of the Alliance updated their position on the future of the Alliance’s mission in Afghanistan.

Several factors contributed to the change in the members’ position; chief among them was the serious deterioration in the security situation before and after the presidential elections held in Afghanistan during August 2009. The sharp increase in Taliban activity toward the end of the summer and early fall of 2009 led to combat losses for the year to that point that exceeded the total number of soldiers killed during all of 2008, making 2009 NATO’s bloodiest year. The dozens of NATO soldiers killed before and after the elections dramatically altered public opinion in France, Italy, Germany and Great Britain; and that could not help but affect the official position of the governments of those countries. So in late 2009 the governments of the major ISAF players revised their vision of NATO’s future involvement in Afghanistan during ministerial meetings in Bratislava (October 22-23) and Brussels (December 3-4).

The vision derives first of all from the steadfast reluctance of the US allies in the Afghan Coalition to send additional forces to Afghanistan. To be sure, the US leadership and military circles in Washington do not share their reluctance.

Second, the European capitals favored the “Afghanization” of NATO’s peacekeeping mission, which would involve the gradual transfer of responsibility for ensuring security in the country to Afghan security forces—the army, police and special services. For that to happen, the ISAF forces need to concentrate their maximum efforts on training the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF)—the army (ANA) and the police (ANP)—which eventually will have to assume full responsibility for security in the country.

Third, because the European members of NATO have placed their reliance on strengthening the training of Afghanistan’s own security forces, attention will turn to sending specialists capable of professionally training Afghans, as opposed to sending military units to Afghanistan. At present, Afghanistan does not have enough units of its own.

I should say that the idea of training Afghan security forces was conceived during NATO’s anniversary summit in Strasbourg and Kehl during April 2009. It was then that a number of policy decisions aimed at strengthening NATO’s non-military role in Afghanistan were made. NATO’s responsibilities for training of Afghan security forces by assisting in the preparation and education of Afghan soldiers and policemen were significantly expanded. The establishment of a NATO Training Mission for Afghanistan (NTM-A) to accomplish this was announced. It is tasked with training Afghan soldiers and educating them in European defense colleges and academies.

The first document to officially make the transfer of total authority for security in Afghanistan to the Afghans themselves a priority NATO goal was the Strategic Concept for the transfer of responsibility for the situation in Afghanistan to the Afghan security forces. This Concept was adopted at the NATO defense minister meeting held in Bratislava during late October 2009.

The new NATO strategy made its second official appearance in the Statement on Afghanistan adopted by the foreign ministers of NATO and the ISAF member countries on December 4, 2009. The document asserted that NATO’s mission would end when Afghan forces are able to ensure the security of their own country.

According to Secretary-General Fogh Rasmussen, in early 2010 there were 60 teams in Afghanistan training army personnel and 100 involved in training Afghan policemen. The Afghan army numbered about 113 thousand soldiers, and there were almost 103 thousand policemen.

And in Tallinn, NATO’s Secretary-General reaffirmed that NATO’s strategy is to gradually transfer responsibility to the Afghans themselves. Based on those statements by the Alliance’s senior official, we can draw the following conclusions about NATO’s future in Afghanistan.

In 2010, we should see the beginning of the transfer of responsibility for the country from NATO to the Afghans themselves. In military language and in accordance with the ISAF Operations Plan, the coalition forces under NATO will initiate Phase 4 (Transition).

Second, the process will be a gradual one. That is, Phase 4 will in places be superimposed on Phase 3, the main objective of which is stabilization of the situation in the country.

Third, the possibility of transfer will be determined separately for each region. This means that, on the one hand, Afghan forces are not yet ready to fully engage in providing security in all regions of the country, while on the other hand the stabilization phase is far from complete.

Fourth, the transfer of responsibility to the Afghans will not mean the immediate departure of NATO forces from Afghanistan, although according to Fogh Rasmussen NATO does not plan to remain in Afghanistan forever.

Indeed, it appears that for the short- and even medium-term, NATO has no choice but to stay in Afghanistan. No one else is prepared to take a leading role in that country—nor is anyone else likely to do so. No other international or regional organization has a more robust or greater military capability than NATO.

Nonetheless, it is logical to assume that the North Atlantic Alliance will leave Afghanistan sooner or later. And that gives rise to the question of when it might occur. The NATO Secretary-General refuses to name specific dates; he prefers to say that everything depends on prevailing conditions, not on the calendar. NATO will leave only when it is one hundred percent certain that Afghanistan’s army and police are ready to maintain order in the country.

Given that, the prospects for NATO’s withdrawal from the country are rather vague. The current strength of the Afghan army and police does not allow Afghanistan’s central government to maintain order independently. The planned increase in the strength of the ANA to almost 172 thousand and the police to 134 thousand is unlikely to change the situation dramatically. ANSF logistics and the quality of the soldiers and officers remain a serious problem. In order to prepare strong professionals capable of effectively maintaining order and resisting the Taliban, extensive training under the leadership of NATO and US instructors will be required, and currently there are too few of them in Afghanistan. Equally important is the ideological orientation of Afghan soldiers and policemen, most of whom join only for financial reasons, because the small sums they are paid amount to substantial earnings in impoverished Afghanistan.

The commitment of the Afghan army to resist the Taliban should NATO and the United States withdraw remains a question. Could NATO officials be overestimating the willingness of the Afghan army to fight? We often hear, including from NATO members themselves, that the Taliban also pay soldiers in the Afghan army to carry out specific operations for them. But even if we assume that the Afghan army is totally willing to fight, and the stabilization phase of NATO’s Operations Plan concludes with complete victory in the guerrilla warfare against the Taliban, the Taliban cannot be totally destroyed in practice. The Taliban will remain—if not in Afghanistan then in nuclear-armed Pakistan. They feel completely at home in Pakistan’s border provinces, and Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have an interest in their continued existence because of the complex geopolitical game that Islamabad is playing in the region.

The Europeans, of course, would like to withdraw from Afghanistan as soon as possible, but considering the Taliban’s continuing guerrilla resistance and the current level of training of the Afghan army and police, as well as a wide range of other factors requiring the presence of foreign forces in Afghanistan, it is premature to speak of a NATO withdrawal.

The real question for NATO and the United States today is how to leave Afghanistan without being victorious, rather than when to leave. The Americans failed early in the military campaign to achieve three important objectives: fully defeat the Taliban regime and render its recovery impossible, defeat al-Qaeda and capture Osama bin Laden. Therefore, NATO should now think about how to leave Afghanistan without losing face.

Its best option could look something like this. Expel the Taliban from the capital and the country’s major cities to the greatest extent possible with a “carrot and stick” policy—destroy the most implacable Taliban and engage a portion of the warlords and the so-called moderate Taliban in negotiations. Use the political amnesty process declared by Barack Obama and Hamid Karzai to draw them into cooperating with the central government and include them in local government organizations. The Taliban must not be allowed to regain strength by calling on all Afghans to unite in fighting the Western Crusaders. Therefore, the policy must always be to split the forces that oppose NATO and the United States.

Finally, they must seriously tackle the drug problem, and that means they must fight the drug trade and the drug kingpins, many of whom are warlords who use drug money to finance their bands. A large proportion of the drug money goes to the Taliban, who have learned to exploit the dependence of Afghan peasants on opium crops as a tool for putting pressure on the ISAF and US forces.

This option is similar to the plan General Petreus implemented in Iraq. The essence of the plan lies in the fact that, although the enemy will continue periodically to carry out terrorist attacks, he will lose overall control over the country’s vital centers, which will allow the European NATO members to gradually reduce the number of their units and transfer the mission of maintaining security to local armed forces under the control of the Americans, whose bases will most likely remain in Afghanistan even after full withdrawal of coalition forces from the country.

In order to achieve real results in Afghanistan, strong efforts are needed not just from the Western and Afghan militaries, but primarily from Pakistan. Yet in contrast to the Americans who are providing significant military assistance to Pakistan’s domestic antiterrorist operations, NATO has no strong mechanisms for cooperating with that country, not to mention instruments of influence. Brussels’ only remaining option is to get the political dialogue that was begun with Islamabad in 2007 back on track, and the Pakistani authorities will go into it with a great deal of suspicion and distrust.

Success in this scenario would provide the maximum benefit under the circumstances, because complete elimination of the Taliban or al-Qaeda is unlikely. A declaration of victory over the Taliban would be essentially false because the Taliban can draw on a virtually inexhaustible reserve of fighters; they are fully capable of conducting guerrilla warfare against any foreign presence in Afghanistan.

NATO’s European members should distance themselves as far as possible from the goals the Americans set themselves at the very beginning and which they have not achieved. If NATO wishes to save face as an organization, it must emphasize the fact that the fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban has always been a US prerogative, and NATO came to Afghanistan in order to lead the International Security Assistance Forces and help the Americans maintain order on the local level, in the rear so to speak, as well as to establish the safest possible conditions for Afghanistan’s development, which has been achieved under the plan indicated.

In the mid-term, NATO’s European countries could present that option as success, since most ISAF forces would have been withdrawn, the situation in the country relatively stable and responsibility transferred to the Afghan forces under US control. The end result of the operation would be recognized as second best, i.e., not the best outcome, but the only possible way out for NATO, all things considered.

Natalya Burlinova is a Russian political analyst, author and international politics host of the radio program “Foreign Factor.”

Source: New Eastern Outlook

What Natalya has stated is simply that the NATO is developing an exit policy from Afghanistan. Now the question is the US policy itself and do they have an exit policy? Historically, no imperialist force has ever succeeded in occupying a country against the will of its people. The Soviets retreated from Afghanistan and so did the US from Vietnam. The British retreated from their empire back to the island but left a mayhem that resulted in the deaths of 1 million Muslims and Hindus and has divided two nations that share a culture.

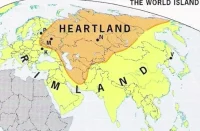

From my understanding developed from so many political analyses, I’ve derived that the Muslim world is fast coming to the realisation that they’re being expolited, largely due to British and Israeli policies. It will take only one country, Pakistan, to get on board with the Muslim world and when that happens, not only NATO but even the US will have to retreat from Afghanistan. Pakistan,Iran and Turkey can be a powerful alliance that can upset the entire western applecart. But first Pakistan will be whipped before it will come to its senses. I see that this will happen very soon.