Christine Stone asks whether the current crisis over the Ukraine’s relationship with the EU was precipitated by the West rather than President Yanukovich.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the demonstrations that have crippled central Kiev for the past fortnight is how they were triggered. Even allowing that ordinary people could be excited by a lengthy technical Euro document like the Association Agreement, why did the crisis over Ukraine’s signature only emerge on the eve of the Vilnius Summit three weeks ago? Is the fairy tale story that a benevolent EU was rejected at the last moment by a scheming Ukrainian president really true? The West and its vocal friends on the streets of Kiev seemed better prepared for the crisis than the President who allegedly caused it by suddenly refusing his signature in Vilnius.

Viktor Yanukovich’s government had been negotiating a partnership agreement with Brussels for several years. The administration in Kiev will have been aware for some time of the heavy burden this would impose on the Ukrainian economy. But, what about the corresponding burden that assuming moral responsibility for Ukraine’s massive debts would impose on the EU? In fact, in the small print of newspapers like the Financial Times some economists raised the alarm. Ignoring the posturing of politicos like Jose-Manuel Barroso and Guido Westerwelle, did the more financially literate apparatchiks in Brussels really want the EU to run the risk of – possibly – accepting the moral hazard of endorsing a state with a debt-mountain and huge installments due early in 2014 ?

At the last minute, and very conveniently, the IMF appeared on the scene to blow the deal apart. On 20th November in a letter to the government in Kiev, it made even more draconian demands before dispensing a new loan to tide the Ukraine over. The terms proposed included hiking gas prices immediately by 40%. To have agreed such a deal would have spelled political suicide for Viktor Yakukovich in his heartland of eastern Ukraine. He decided to walk away. Afterwards, the Ukrainian opposition and the West laid the blame not on the IMF’s oppressive conditions but on the evil, machinating Russian President Putin. According to this version of events, the Russian president had threatened Yanukovich with economic Armageddon if he signed the agreement. Putin himself denied any strong arming and the facts rather speak for themselves in that the Russians had been saying for years that they could not support the Ukrainian-EU deal as it went against their own economic interests by for instance turning the Ukraine into a free trade conduit for Euro exports to Russia while requiring Kiev to cut back on imports from Russia. Nothing new had happened from Moscow’s perspective to derail the deal at the last moment.

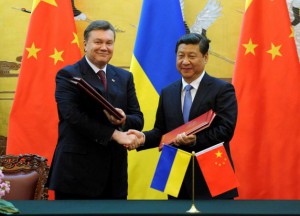

Since then, Yanukovich has been out with the begging bowl and, on 5th December, returned from China with the promise of inward investment totalling $8 bn. On his way back to Kiev, a visit to Mr. Putin in Sochi netted him more economic benefits if reports in the Ukrainian media are to be believed. “Earlier on Friday, zn.ua reported that Ukraine was allegedly negotiating with Russia on obtaining a loan of at least $12 billion, as well as possible signature of a new contract between Gazprom and Ukrainian private companies on the supply of 10 billion cubic meters of gas at a price of $210-230 from January 1, 2014”. Who knows what other (unpublicised) goodies were in his swag bag? And, despite the rumours, Yanukovich did not indicate that Ukraine would enter the Russian-sponsored Customs Union any time soon. Instead he has reiterated his ambitions for entry into the EU.

In other words, Yanukovich could have been playing a slippery game. By turning down the Partnership deal, Yanukovich has let the Europeans off the hook. Instead of Brussels being asked to fund Ukraine’s debts, they seem likely to be sorted out, for the moment anyway, by Mr. Putin and the Chinese. As if on cue, the IMF has reappeared with a more “positive signal”. On 9th December, the Ukrainian Minister of Revenues and Duties, Aleksandr Klimenko tells Ukrainian 1+1 television station that the IMF has come forward with a new deal that is much more appropriate for the country’s needs. Gone are the demands for an immediate 40% hike in energy bills. Now, increases can be ‘gradual’. So far, no more flesh has been put on these bones. But, the prospect must now arise that the Partnership Agreement could be ‘revisited’ and, who knows, signed by Kiev with the knowledge that the debts which previously overshadowed the whole arrangement have been ‘settled’.

But, what about the political demands? The opposition’s calls for the resignation (or overthrow) of the government and president? Despite the roll call of Euro politicians traipsing through the maidan, not everyone agrees about that. On 9th December Polish Defence Minister, Radek Sikorski, one of the most virulent anti-Russian, pro-EU politicians closely connected with EU-Ukrainian negotiations, said that people should stop demanding Yanukovich’s resignation. “I believe that the demand for the resignation of the president is a political mistake, because he may decide on forming a coalition government or signing the Association Agreement” he is reported saying on 9th December. Perhaps, if the deal, is signed all those people will melt away from Euromaidan (as it is now called by the opposition). After all, despite the huge effort put into getting the Orange Revolutionaries (Yushchenko, Timoshenko et al.) into power, once they fell out, no one returned to Kiev’s maidan to demand another revolution.

When Yanukovich was elected president in 2010, the OSCE – always a barometer of the West’s geopolitical interests – praised the conduct of the poll and urged his opponent, Yulia Timoshhenko, not to challenge the results! This is not to say Brussels and Washington like the Ukrainian president but, as a compliant and cowed Euro-poodle, the West might agree to live with him and his government – at least, until another crisis is manufactured, maybe in time for the 2015 elections.

If Yanukovich survives and the EU agreement is revisited, what happens next? The old, familiar problems will remain: a bifurcated country with no real prospect of harmony between east and west. Talk of splitting it up is a non-starter as the Washington consensus does not want the impoverished western Ukraine to join the EU without the east – despite the propaganda over the years hailing this miserable back water as ‘European minded’ and so, implicitly, more prosperous than the industrial east. In fact, it is the lack of prosperity in western Ukraine that has driven the protests in both 2004 and 2013: the young, many of whom already provide cheap labour in Europe want the visas (and maybe, one day, even EU membership) that would make their departure from home so much easier.

The prize for the West is the Ukraine’s south (i.e. the Crimea and Black Sea coast) and the east with its long border with Russia. By impoverishing these regions (as the Partnership deal is set to do), the Eurocrats conclude they will be in a better position to undermine Russia. Anyone looking at how the economies of the Baltic States, Poland, Romania or Bulgaria were hollowed out before accession to the EU and the mass migration of the destitute losers, especially the young, can see a well-tested model in play again. A depressed and depopulated Ukraine is what the EU wants to associate with. Under Brussels’ thumb, such a Ukraine will be likely to renege on its residual security arrangements with Russia such as its basing rights for the Black Sea fleet in Crimea.

For now the Ukraine is sinking deeper into an economic morass. The impotence of Yanukovch’s government in the face of street occupations and mob violence is symptomatic of its intellectual paralysis. How can a government which lets 2,000 people block its capital’s main thoroughfare with gimcrack barricades and tents be expected to think strategically about the country’s real interests and needs? This hardly the behaviour of a regime run by Machiavellian masterminds whatever the Western media claims. Kiev seems intellectually as well as financially bankrupt.

Christine Stone is a UK-based lawyer and journalist. She was Director of the British Helsinki Human Rights Group. She is the coauthor of Post-Communist Georgia: A Short History with Mark Almond (St. Margaret’s Press: Oxford, 2012). Their next book in the series on Post-Communist societies will be The Post-Communist Ukraine: A Short History in 2014.

Source: Oxford Crisis Research Institute

Pingback: Does the EU really want Ukrainians or just thei...