(Please read Parts I, II, III, and IV prior to this article)

The Ethnic Time Bomb Of Greater Uzbekistan

Central Asia’s most glaring socio-political vulnerability is the idea of a Greater Uzbekistan that links the titular state with its neighboring diaspora in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The following are situational descriptions for each of the countries that could predictably fall victim to this geopolitical project:

Kazakhstan:

On the surface, it doesn’t appear as though Greater Uzbekistan is a threat for Kazakhstan, since the 2009 census lists only 2.9% of the population as belonging to this minority group. Looking closer, however, there’s a significant regional divide in these statistics, with an estimated one-fifth of the population of South Kazakhstan province (out of a total of over 2.5 million) thought to be Uzbek. The CIA World Factbook believes that Kazakhstan’s population was a little over 18 million at the beginning of 2015, so taking into consideration that at least 500,000 Uzbeks lived in South Kazakhstan, then that’s almost as much as the 2.9% national total. This doesn’t take into account the tens of thousands of Uzbeks that could realistically be living and working illegally in Kazakhstan (likely in South Kazakhstan), so the number is probably a bit larger than officially estimated, but the saliency in this general overview is that it’s proven beyond doubt that about 93% of Kazakhstan’s official Uzbek minority lives in the border province of South Kazakhstan.

From this determination, it’s a lot easier to understand the possible risk that Greater Uzbekistan poses for Kazakhstan. Although still a minority in South Kazakhstan, ethnic Uzbeks have a sizeable presence, and if they organized and united under a common banner in pursuit of a shared cause (in this instance, Greater Uzbekistan), then they could certainly be a political force to contend with. Their strategic location along the Uzbek border naturally makes the irredentist project enticing for some in Tashkent, but at the same time and under specific conditions, it could be used as a 2010-like strategic trap for sucking Uzbekistan into a conflict not of its own choosing. The scenarios under which Greater Uzbekistan could be born will be explored after the situational description of the other two targeted countries and some brief words about the tactical innovation that a Third Central Asian Spring attempt could realistically entail.

Kyrgyzstan:

According to a 2009 estimate by the CIA World Factbook, ethnic Uzbeks are 14.3% of the total Kyrgyz population, and the BBC points to most of them living in the Fergana Valley, specifically the ‘crescent’ linking Jala-abad with Osh right near the border with Uzbekistan. Therefore, just as with Kazakhstan, but even more so in terms of population percentages, the majority of Kyrgyzstan’s Uzbek minority live within a very short distance of their titular state and are thus exceptionally vulnerable to suggestions of a Greater Uzbekistan. The ethnic conflict that embroiled the country in 2010 increased the sense of identity solidarity among this demographic, and in ‘defensive’ response to any repeat of such events, it can be assumed that they’ve created ‘protective’ committees (militias) that would be activated the moment violent once more erupts. From the standpoint of Greater Uzbekistan, these networked and organized individuals could be used as a vanguard force in actualizing this geopolitical ideal when the decision (or provocation) for its implementation has been made.

Tajikistan:

The ethnic divide in Tajikistan is very similar to that of Kyrgyzstan, in that 13.8% of the population is Uzbek. Similarly, most of these reside in the northern ‘neck’ of the country where Tajik territory strategically intersects the most geographically convenient route connecting Fergana with the rest of Uzbekistan. There are also some populations living in the western part of the country to the east of Samarkand. All comparisons with Kyrgyzstan stop at this point, however, since Tajikistan’s historical-political context is vastly different than that of its neighbor and less fertile for Uzbek nationalists to exploit. Tajik identity is very strong and deeply established, and the historical rivalry with Uzbekistan forms a fundamental part of it.

Many Tajiks resent that the large parts of their claimed homeland near Samarkand and westward thereof were given to Uzbekistan in the 1930s and “Uzbekified” afterwards, and they feel as though their general identity as a nation-state is under threat from their larger and imposing neighbor. The bilateral tensions that have been prevalent since independence didn’t do anything to soothe over these fears. Continuously on high alert for any provocations (border, internal, or otherwise) attributed to Uzbekistan, and historically having to defend themselves from Greater Uzbekistan, the Tajiks are the least likely of the three discussed Central Asian states to be caught off guard by this irredentist plan if it’s ever pursued. They would fight tooth and nail to prevent it from happening, and that of course would lead to a conventional war with Uzbekistan in the meantime, which might have been the original intent all along in that scenario.

The Islamic Improvisation

It is highly expected that the third attempt at a Central Asian Spring would combine the 2010 ethnic-centric innovation with a strategic improvisation that reflects the global zeitgeist of Islamic-affiliated terrorism. This would take the form of ethnic Uzbeks in Uzbekistan (centering on Fergana) and the neighboring states resorting to the doubly ‘unifying’ ideologies of Greater Uzbekistan and Wahhabist extremism in order to fight for the creation of a Central Asian caliphate. The borders of this terrorist entity would roughly correspond to the same territory that Greater Uzbekistan encompasses, so it would be a highly effective overlap of strategic vision as seen from the US’ perspective of planned regional destabilization.

The terrorist wars being fought in Syria/Iraq and Afghanistan by ISIL and the Taliban, respectively, already serve as valuable battlegrounds where fighters can hone their experience before applying it back home. Proving that an ethnic Uzbek-led terrorist campaign is already being planned for Fergana, Kyrgyz officials allege that the majority of extremists that have left their country for terrorist training come from the Uzbek minority, suggesting that this demographic is more susceptible to radical Islamic ideologies than any other in the region. The Kazakh and Kyrgyz have traditionally been more open and liberal when compared to their Uzbek neighbors, and Tajiks fought a bloody 1990s civil war against Islamists that most of the population isn’t eager to repeat again anytime soon. The Uzbeks, however, have always been more religiously conservative, and thus are increasingly vulnerable to the extreme rhetoric being spewed by ISIL and the Taliban.

A militant convergence between proponents for a Greater Uzbekistan and terrorists fighting to carve out a Central Asian caliphate is thus a very realistic possibility, and it’s one that should be taken with the utmost seriousness by all regional leaders, Uzbek ones included. It will be argued in the coming section that these two expansionist and violent ideologies risk drawing Tashkent into a conventional confrontation with its neighbors even if it has no prior intention of doing so, and in the absence of any effective government in a post-Karimov scenario, could prove to be the ultimate catalyst for a Central Asian meltdown.

The Third Time’s The Charm

From a structural standpoint, all of the necessary socio-political vulnerabilities (focusing first and foremost on Greater Uzbekistan and Islamic-affiliated terrorism) are in place for the US to initiate its third attempt at a Central Asian Spring. If it goes forward with such a plan, it would predictably take one of three general forms:

Leading From Behind With Uzbekistan:

Under this scenario, Uzbekistan becomes the US’ Lead From Behind proxy leader and a bastion of pro-American influence in the heart of the region. Its leadership is closely aligned with the US’ strategic vision for Central Asia, and Washington is encouraging Tashkent to utilize its neighboring diaspora in exerting pressure on Russian allies Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Prodded on by the US, Uzbekistan becomes increasingly assertive in promoting the rights of its ethnic compatriots, taking their side in disputes even if they’re objectively to blame for inciting disorder (whether explicitly anti-government or focused more against local actors). The combination of a restive Uzbek diaspora in the neighboring periphery and a newly emboldened leadership eager to defend their interests culminates in a stage-managed “National Awakening” akin to the “Arab Spring”, where this ethnic group simultaneously agitates for unification with their titular state and consequently provokes a regional crisis.

The US might be interested in pursuing this strategic path if it wants to start a New Cold War proxy conflict right in Russia’s strategic backyard, using its state ally of Uzbekistan instead of depending on terrorist forces. The relative advantage that the US could seek from this course of events is to weaken one of Russia’s allies (most predictably Kyrgyzstan, the weakest and most vulnerable of the three) and perhaps provoke the CSTO to intervene. With Russia focusing on fighting terrorism in Syria at the moment and cautiously monitoring Eastern Ukraine, it conceivably wouldn’t feel be inclined to spread its resources too thin and jump head-first into an interstate conflict in Central Asia, so the potential exists for the US and its Uzbek ally to exploit this strategic opening in advancing their irredentist and destabilizing agenda. Furthermore, if Tashkent could be talked into instigating what could possibly turn into a full-scale regional conflict and ends up on the losing side, then the US could ‘lend a helping hand’ by deploying its ethnic Uzbek terrorists to fight a stay-behind ‘liberation’ jihad against the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and/or Tajiks.

If the US and Uzbekistan reach an arrangement for the latter to be Washington’s Lead From Behind proxy in Central Asia, then that means that the US would support the country through its inevitable leadership transition and help to mitigate the chances that it falls apart in the process. This is because the US would have a strategic stake in Uzbekistan’s stability for the time being, and would be wagering its bets on being able to disrupt Russia’s Eurasian Union integration processes a lot better by using Uzbekistan than turning on it. However, the US has shown itself willing to betray all sorts of allies in its quest for global dominance, so there’s no assurance that Uzbekistan would be spared from this traitorous pattern. More realistically, the US could exploit a ‘strong and stable’ Uzbekistan to its fullest geostrategic potential before preemptively taking steps to weaken it from within through clannishness and Islamic terrorism in order to keep it in check and make sure it doesn’t ever feel that it could do without the US or go against its dictates with impunity.

Another Shot At The Reverse Brzezinski:

The second potential circumstance under which a Central Asian Spring could be commenced is in the US promoting an Uzbek “National Awakening” outside of coordination with its Tashkent counterparts. It would do this to stoke regional tension and provoke a situation where Uzbekistan is forced to respond in some manner to a crackdown against its ethnic kin next door. Not having anything to do with the provocations in the first place, Tashkent would be extremely reluctant to respond outside of the diplomatic sphere, but it might find itself drawn into escalating its denouncements and potentially even mobilizing its military as a show of force if such incidents repeat themselves, let alone in a short time frame and all across the region.

Uzbekistan wouldn’t want to support an irredentist movement, but it could find itself coming under domestic pressure to do so, either by segments of the population or influential decision makers and personalities. If Uzbekistan-based Uzbeks rallied in support of their compatriots abroad and Tashkent, fearing that this is advance cover for a forthcoming Color Revolution attempt, came down hard and forcefully dispersed them (maybe even resulting in a handful of casualties and a few fatalities), it could reversely engender the same type of externally directed uprising that the authorities were trying to avoid. This becomes even more acute if Karimov is on his deathbed or very close to it and the country is on the cusp of its inevitable leadership change, since rumors of the dying leader could quickly combine with nationalist fervor all throughout the region to create an explosive combination of populist resent and “activism” that culminates in the EuroMaidan-like destruction of Tashkent, led of course by Islamic jihadists (the ideological equivalent of Pravy Sektor in this case).

The US’ aim in this scenario is to accomplish what it had initially failed to do back in 2010, which is set off a fratricidal region-wide war between the ‘-stans’ that would holistically lead to each of them being irreversibly weakened. In the resulting tumult, it’s very probable that Russia might have to intervene against its better judgement, being forced to do so to as minimal of an extent as possible in order to safeguard its fellow CSTO allies from external Uzbek aggression while struggling to make sure it doesn’t spread its forces too thin in the meantime.

The only way that this scenario branch would occur is if Uzbekistan can be lured into enacting a conventional military response against any of its neighbors to punish them for cracking down against (rioting) ethnic Uzbeks, as without a formal intervention, this overall scenario remains limited to mostly containable domestic destabilization within the target state(s) (e.g. Kyrgyzstan) and Uzbekistan (if the NGO-influenced nationalists protest against the government’s perceived inaction). Therefore, in the strategic sense, the success of one “Reverse Brzezinski” (Uzbekistan being lured into intervening abroad) would lead to the high likelihood of a second one (Russia defending its CSTO allies), but everything is dependent on manipulating the Uzbek diaspora so as to strategically trick Tashkent into making the first move.

The Chaos Multiplier:

The last likely scenario under which the US could promote a third iteration of the Central Asian Spring would be as a chaos multiplier amidst an independently existing (but no less American-influenced) regional disorder. Examples of this could be a Color Revolution in any of the four examined states, an international conflict over the numerous enclaves that dot the region, and/or a successionist crisis in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and/or Uzbekistan. The point here is that while each of these ongoing scenarios are destabilizing in and of themselves, the introduction of a Greater Uzbekistan and/or Islamic jihad movement into the mix could be the critical factor that leads to the situation spiraling disastrously out of control and towards the pan-regional chaotic path that the US intends for it.

It’s theoretically possible that each targeted state could manage and contain each crisis, but non-state actors outside the control of any of them and fighting for a transnational vision could dramatically unbalance whatever the present state of affairs is at the moment. They could also be deployed to sabotage any prospective diplomatic solution at the very last minute and be utilized to add another more complicated dimension of discord to already strained bilateral relations between Uzbekistan and either of its relevant neighbors. Because of the relationship that the Uzbek government may be suspected of having with the proponents of Greater Uzbekistan, the sudden emergence of this movement could be timed to falsely implicate Tashkent in whatever violence its American-controlled on-the-ground advocates commit, thus potentially even inviting a conventional response from any of the three affected CSTO members (made more likely if it occurs during a post-Karimov unravelling of the state and the absence of any effective government).

There’s no way to predict all the ways in which the strategic insertion of the two militant ideologies of Greater Uzbekistan and Islamic jihad (or a hybrid of both) could shatter the fragility of Central Asia, but it can generally be assumed that either of them would have a radically destabilizing effect on regional relations and increase the potential for conflict between each of the relevant states. This is why the final scenario is referred to as the chaos multiplier, since it’s intended to demonstrate that the active implementation of one or both of these two ideologies would take Central Asia in a completely unpredictable direction and do so with a rapidity that overwhelms the decision-making apparatus of each involved state. In the strategic paralysis that’s sure to follow, it’ll be the US and its non-state proxies that determine the subsequent course of events and guide the dynamics of the unfolding uncertainties.

Comparing The Chaos: A Back-To-Back Analysis Of The Uzbek And Turkmen Scenarios

Uzbekistan:

To finally conclude the analysis on Hybrid War in the Greater Heartland, it’s appropriate to offer some closing words on why Turkmenistan was earlier designated as being a more impactful target than Uzbekistan, given all that was spoken about before. Of course, destabilization in Uzbekistan serves very important objectives that are designed to disrupt the functioning of multipolarity, specifically the cohesion between Russia and China. Disjoining these two multipolar centers via orchestrated chaos in Central Asia is no small feat, and would definitely have global repercussions. Snipping the Russian-Chinese Strategic Partnership right at its geographic source in terms of shared energy, economic, and geographic stability interests would be a hard blow to each of them and undoubtedly unbalance them to various degrees. The terror nest that could be built in the Fergana Valley would serve as a convenient training ground for nearby Xinjiang terrorists, and wide-scale disorder in Uzbekistan could prevent the safe and timely transit of Turkmen gas to China. Last but not least, the resulting refugee flows that this would trigger might predictably be used as a guided weapon of asymmetrical destruction against Russia, with the intent of overwhelming its Central and Siberian provinces by mass human transit through Kazakhstan just as their Mideast equivalents are doing against Central and Northern Europe via the Balkans.

Turkmenistan:

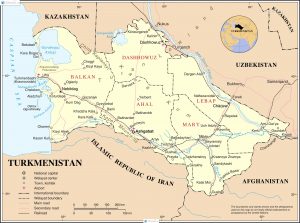

Turkmenistan’s destabilization, while being based on a comparatively less complicated scenario, could actually be more globally impactful than anything which happens in Uzbekistan. To remind one of Turkmenistan’s global significance, it’s turning into “Eurasia’s Gas Station”, especially since it supplies China with so much of this resource and is expected to do so to India in the next decade as well. Lesser amounts are sent to Russia and Iran, so taken together, it’s accurate to say that the most relevant multipolar states in the world today are, or stand to be (in the example of India), supplied with Turkmen gas to varying degrees. China has a disproportionate dependence on Turkmen gas, so it would be the most directly and visibly affected if terrorists overrun or threaten any of the gas fields located in close proximity to the Afghan border. Unlike Uzbekistan, the Turkmen military isn’t battle-hardened and its capabilities are unassessed but generally assumed to be lacking in quality. Any Color Revolution attempt in Ashgabat or elsewhere in the country could be met with a disproportionate military reaction that shortsightedly shuffles the arrangement of security forces across the country and unwittingly creates a border vulnerability. Figuring in that Turkmenistan is institutionally a ‘sitting duck’ owing to its “neutral” non-participation in either the CSTO or SCO cooperative frameworks, then there’s a real and striking possibility that it could fall victim to a sudden terrorist offensive that overwhelms its military defenses and immediately impacts on China’s resource supply.

Turkmenistan’s vulnerability to an ISIL-like terrorist offensive is all the more important because the country’s location dictates that any destabilization there could quickly travel to western Kazakhstan (previously the site of the Zhanoazen riots), western Uzbekistan (where the externally organized Karakalpakstan independence movement is being built as a reserve proxy force), and northern Iran. There is no way that Russia and its CSTO allies would allow terrorists to repeat ISIL’s success along the Syrian-Iraqi border in Central Asia along the Afghan-Turkmen one, so some degree of military intervention could be expected in this scenario (even if only limited to cruise missile strikes). Moreover, terrorist threats to Turkmenistan’s gas fields would inevitably lead to a sudden spike in the gas price, especially if something happens to disrupt transport to China and Beijing reactively searches for replacements elsewhere. While gas-exporting states would obviously benefit from this economically fortuitous course of events, the majority of the world that imports this resource and has already budgeted a lot less for their yearly allocation would be taken off guard and put at a strategic disadvantage, especially if China’s replacement imports seriously disrupt the existing LNG supply chain (which is expected to become even integral to the global market in the coming future).

Interrelated Destabilizations:

A similar economic reaction could take place simply through the disruption of Uzbek transit owing to a nationwide destabilization there, but because the problem wouldn’t be originating at the source but through one of the secondary states, the impact that this has on the global market isn’t expected to be as impactful as if terrorists seized or sabotaged one of the world’s largest fields in Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan’s destabilization is more of a nightmare scenario for Russia and China, while Turkmenistan’s equivalent would affect both of this plus Iran and China. Interestingly enough, both general scenarios about chaos in each of those two countries are somewhat intertwined, since the occurrence of could directly increase the likelihood of the other. If a terrorist invasion of Turkmenistan is launched near the east of the country by the Amu Darya river (which is where the Taliban were concentrating in late October) and overwhelms the national authorities, then an Uzbek military support operation might be one of the only immediate and realistic solutions to effectively stem the advance and hold the frontline position until a more feasible response can be mustered. Iranian intervention could also be an option if such a scenario occurs closer to its borders. Likewise, the fulfillment of any of the Central Asian Spring scenarios would create an unprecedented black hole of regional chaos that could embolden transnational terrorist groups and destabilize the structural security of the Turkmen state, thus increasing the odds that a terrorist spillover would occur sooner or later.

Final Judgement:

It’s difficult to separate these two destabilizations, despite how different they may have initially appeared to the reader before this section. They don’t necessarily have the same immediate impact, but in general, they do share the common denominator of cause-and-effect and eventual energy market consequences. It seems much more likely that a Hybrid War will break out in or around the Fergana Valley than it will across the Afghan-Turkmen frontier, and the aftermath of the former would obviously disrupt Russian-Chinese cooperation a lot more than the latter. However, the overall effect of a terrorist invasion of Turkmenistan (perhaps accelerated by a preceding [American-influenced] Color Revolution attempt) would have the grandest impact because of how it would affect Iran and India as well, and also because it creates a much more favorable (and thus, likely) possibility for an urgent Russian-led military intervention that could divert Moscow’s strategic focus on Syria and Ukraine.

The risks of doing so in Fergana are noticeably higher (even if the stakes of not doing so are equally the same), so it’s more difficult to predict how Russia will ultimately react. With Turkmenistan, because the prospective operation gives off the veneer of being simpler and less of a quagmire (e.g. it could theoretically be conducted only through air support), it’s much more expected that Russia will conventionally intervene in one form or another. The large-scale refugee risk emanating from Fergana is certainly a formidable challenge, but a combination of factors could deter its asymmetrical effectiveness against Russia.

Firstly, the vast Kazakh steppe could absorb the refugees and act as a security net in preventing their eventual arrival in Russia.

Secondly, the present crisis in Europe is structurally engineered and aided by established criminal networks. Russia doesn’t follow the liberate dictates of its EU counterparts and would forcefully crack down on these entities and destroy the infrastructure which they use to operate (social, financial, physical, etc.). Also, Russia is capable of quickly shutting down and/or securitizing its (former) border checkpoints with Kazakhstan (despite the Eurasian Union and the theoretical elimination of such barriers) if a crisis arises, or sending reserve forces to the Kazakh-Uzbek border to assist in controlling the flow of the fleeing masses.

Finally, Moscow has no qualms about immediately carrying out a strict deportation policy in its major cities to set an example to would-be undocumented refugees (as in those that didn’t enter the country through the legal, organized channels) that there is zero tolerance for lawbreakers no matter what the reason for their infringement might be.

Therefore, it’s theoretically possible for Moscow to leverage Kazakhstan’s geography and its brotherly relations with the government in mitigating the worst-case scenarios of a Central Asian Spring, but make no mistake about it – there will undoubtedly be many negative repercussions. Still, however, they’ll be largely contained to the Fergana Valley and will probably not migrate that quickly over the Kazakh steppe, the Kyrgyz mountains, or the Turkmen Karakum desert. The same can’t be said for Turkmenistan’s destabilization, however, since if it happens according to the scenario envisioned in the research, then it could immediately affect the other two countries of the eastern Caspian (Kazakhstan and especially Iran), as well as the sparsely populated and under-defended areas of Uzbekistan immediately east of the Amu Darya. The instantaneous global energy ripples that a threat to Turkmenistan’s globally renowned gas fields would have automatically qualifies it as a scenario of leading impact, even despite the wider Hybrid War implications of the possible forecast. For all of the abovementioned reasons, a Hybrid War is a lot more likely in Uzbekistan, but if one happens to occur in Turkmenistan, then the overall impact would be a lot wider and more structurally influential.

Andrew Korybko is the post-graduate of the MGIMO University and author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland (V) | Protestation

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland (V) - by Andrew Korybko - GPOLIT

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland (V) | Réseau International (english)

Pingback: Usbekistan og hybridkrigen | Steigan blogger