Someone once made the apt observation that оf all those who preached the Gospel in Great Britain in the 20th century there were only three whose voices truly carried weight: – Gilbert K. Chesterton, Clive S. Lewis, and Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. It is worth taking a closer look at these three “last of the Mohicans,” because it is work like theirs that is most essential to any society that is trying to retain its bonds with Christ and the Church.

Chesterton and Lewis were laymen. They held no place in the church hierarchy, nor did they bear the official seal of any seminary or theological school. Thus they were free in a very specific way. At times when a bishop or priest might find himself second-guessing the opinions of his superiors on a particular matter or having to consider how something might play out in the public sphere, etc., those two were free to say what they thought, winning over their listeners with their lack of guile and bold sincerity. They were not prompted to speak out of necessity or because of the obligations imposed on them by their office or position in society, but were motivated by nothing more than faith and heartfelt concern. Each of them began life as a poet. But they won fame: one as a journalist, essayist, and critic; and the other as a writer and apologist for the basic principles of Christian belief, a sort of catechist based on his own academic background.

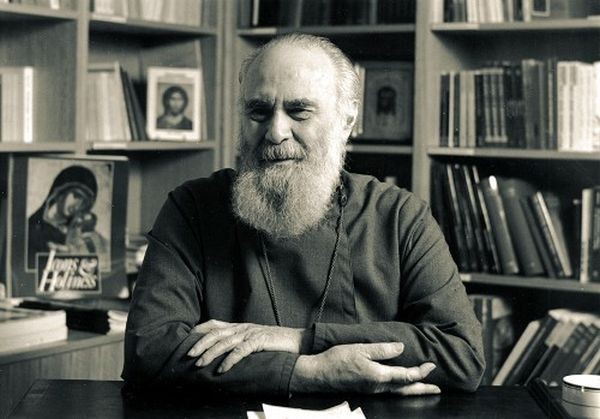

Unlike the other two, Metropolitan Anthony is not a writer or a professor, not a journalist or a polemicist. He is a witness. His words are always a testimony on matters that seem to have been clear to him since childhood. But His Eminence Metropolitan Anthony always knows how to infuse the familiar with the kind of depth to which few others would dare plunge. His voice is passionate and highly credible, his words arising from his personal experiences and deep conviction of the truth of which he speaks. He is always able to reveal the Gospel afresh to his listeners. In his mouth the Word of God is never dry and never boring. He does not browbeat his skeptics by wielding quotations like a cudgel. But he pours out the Word like oil, healing souls from the wounds of their unbelief, worldly vanities, and irresponsibility.

None of the three were cradle Christians; all turned to faith later in life. Each of them was able to offer an honest account of his own doubts, of his search for God and discovery of Him. This engaging honesty had the power to touch the very heart of the modern man who fears tradition and for whom Christianity carries “too much baggage” held over from past eras. Operating from within that tradition, affirming it rather than rejecting it in any way, the three evangelists resurrect the Gospels by breathing fresh air into them. There is no better way to put it – heard from their lips, the New Testament is truly New and the Gospel is truly good news.

It is curious that, unlike Chesterton and Lewis, Metropolitan Anthony never wrote anything. He used the Socratic method: asking and answering questions, keeping silent at times, and thinking aloud in front of God and his audience. Only later were his speeches transformed into books, thanks to the efforts of his friends and admirers. Fortunately he lived during an era in which it was possible to make audio recordings, and so the efforts of scribes were not needed. And by the way, about that era: technical progress, a growing population, a time that was out of joint, and a broad sense of upheaval … Who has not disparaged the most recent events and the spiritual savagery of the contemporary human anthill?! “What dreadful times are these, what dreadful hearts!” But that era nevertheless made possible the use of technology to reproduce the speeches of the wise and to deliver those addresses to thousands and millions of listeners:

Ideally every city needs to have its own Metropolitan Anthony, every university needs its own C. S. Lewis, and every newspaper its own G. K. Chesterton. But alas, such people are rare, and a world in which only their smallest group of followers and associates would have the opportunity to hear them would be an irredeemable loss for many. In the Middle Ages, given the illiteracy of the majority of the flock, the exorbitant price of books, and the lack of any kind of mass communication, everything was dependent upon your opportunity to personally hear the words of the wise as they were spoken. Today, despite the separation of time and distance, we can be instructed by the blessed Word, with the help of books and a variety of audio and video recordings. All three of them understood this. All three of them, at various times and with varying intensity, spoke on the radio, offering talks, lectures, and sermons. In this way they were quite modern, so as to be understood by the man of today, while still keeping their eyes fixed on eternity, so as to avoid the trap of catering to passing tastes, instead defending or proclaiming the truth.

We need these three, bearing other surnames of course. We need fencers, like Chesterton, who are prepared to pull from their scabbards a sharp sword of incontestable arguments, forcing the surrender of any skeptic or unprincipled critic who disparages what he does not understand. This would be the most suitable format for any type of journalism.

We need professors who feel far more at home in the company of ancient manuscripts than electronic screens. These – the ones who summon aid from a vast host of writers and poets from the past – are the ones who are able to stand before the gaze of an indifferently educated public and present Christianity as a source of bountiful strength and a giver of great joy capable of setting hearts ablaze.

Finally, we need bishops who are able to talk about Christ, not as someone speaking down to us from above, but as someone standing directly before us, not as someone lecturing us, but as someone generous enough to share with us the truth.

These three are needed in any society that considers itself educated and intelligent; a society that is perhaps even somewhat bored with its feigned omniscience and, like Pilate, shrugs its shoulders and asks: “What is truth?” Simple people need simple preachers. But simplicity is vanishing. In its place we are seeing the arrogance of the half-educated who are always ready to argue with God because they lack learning. We are growing accustomed to simplistic commentary on complicated subjects and, when faced with eternal questions, a reluctance to offer our own answers that come from our own authentic, first-hand experience. It is those people who have been infected with the contagion of metaphysical frivolity for whom it would be useful at some unexpected moment of their life to come across one of these three: Chesterton, Lewis, or Metropolitan Anthony.

Adapted and translated by ORIENTAL REVIEW from the Russian source.

Comments