With the establishment of the National Council of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs in Zagreb, as well as with the proclamation of the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs at the end of October 1918,[i] a new political situation emerged with regards to the creation of almost a single South Slavic state (without Bulgarians). The Serbian Government found itself in a virtually new situation in which the creation of Yugoslavia had to be again negotiated at a new conference and with a new political actor. Now, instead of the Yugoslav Committee (created with a great influence and support by the Serbian Government, and which was envisaged by it as its propaganda agency and mainly depended on Serbia’s financial support), the Serbian Government should make a new political agreement with a much stronger and more independent political institution, which was not at all dependent on the Serbian Government, either from political or financial points of view.

Moreover, the National Council in Zagreb was presenting itself as a real political representative institution of the South Slavs from Austria–Hungary and a real Government of a newly proclaimed state with a capital in Zagreb. Actually, the upcoming political negotiations should be held between two states: the Kingdom of Serbia (internationally recognized) and the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs (internationally not recognized and with the Serbs as a majority of its population). The main aim in the coming negotiations with the Serbian Government from the side of the National Council was to modify the 1917 Corfu Declaration’s decisions with reference to the governmental type of the new state. On the opposite side, the crucial aim of the Serbian Royal Government was to retain all resolutions from the 1917 Corfu Declaration, negotiated with the Yugoslav Committee in Greece.

The 1918 Geneva Conference

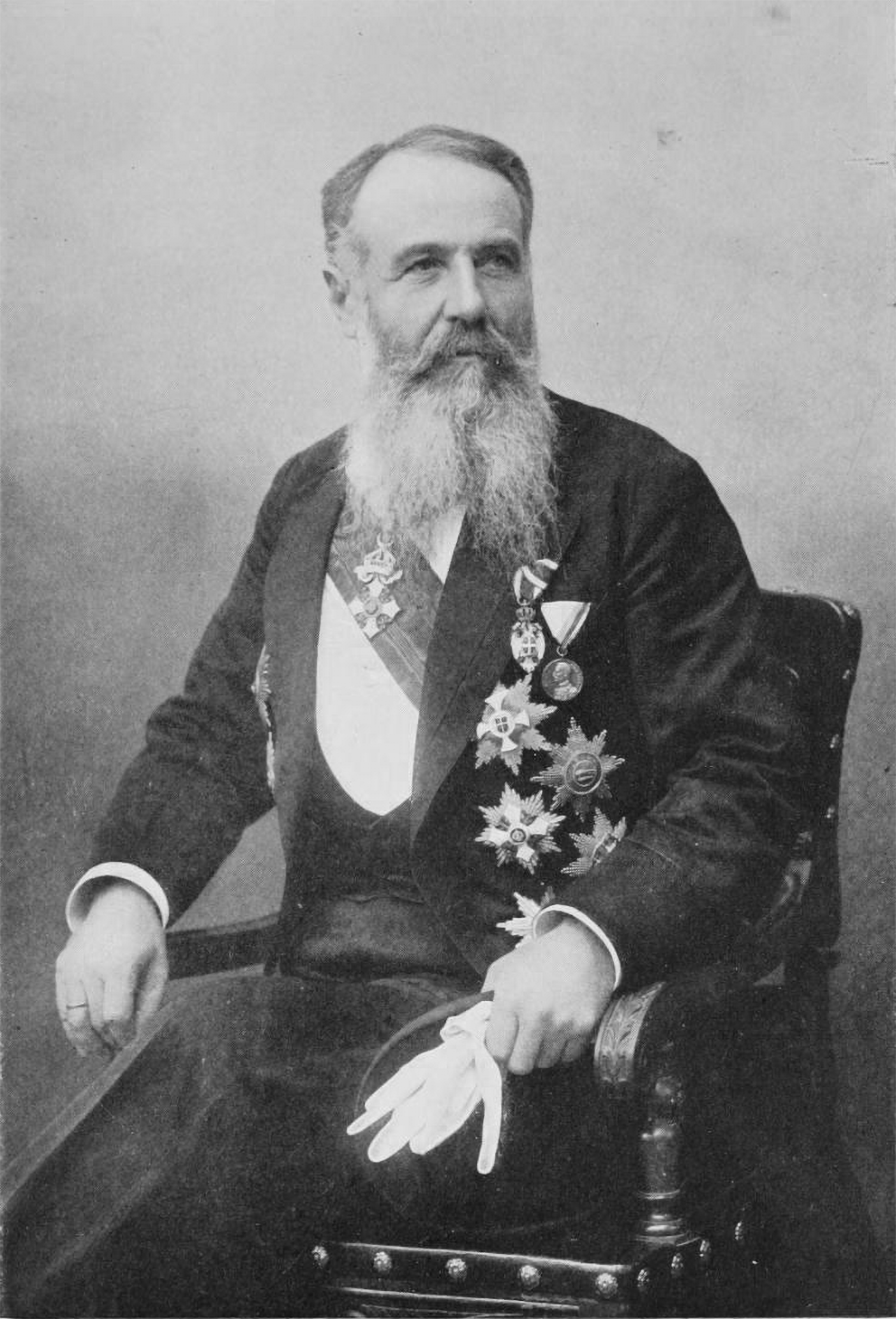

The 1918 Geneva Conference, as a final stage of the negotiations between Belgrade and Zagreb about the creation of a common Yugoslav state, followed by the political agreements in regard to the creation of Yugoslavia, was held from November 6th to November 9th, 1918. Formally, the four different political groups negotiated at this conference: the Serbian Government (represented by its Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs – Nikola Pašić), the National Council in Zagreb (3 representatives), the Yugoslav Committee in London (3 representatives) and Serbia’s parliamentary opposition (3 representatives).[ii]

In effect, it was mainly arbitration between the strongest political factors of the Serbian Government, represented by Nikola Pašić on the one hand, and the National Council of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, represented by its president – the Slovene Roman Catholic priest Dr. Anton Korošec on the other hand. The Serbian parliamentary opposition parties supported during the whole war all demands by the Yugoslav Committee in London as well as from October 1918 the requirements by the National Council in Zagreb. They even openly threatened the Serbian authorities that in the case of a total discord between N. Pašić and the Yugoslav Committee they will support the latter and work against the Serbian Government.[iii] That was a crucial reason why the National Council in Zagreb and the Yugoslav Committee in London required that Serbia’s opposition parties would take participation at the Conference of Geneva to finally agree about the creation of Yugoslavia.[iv]

However, truly speaking, from the very legal point of view, neither the Yugoslav Committee in London nor the Serbian parliamentary opposition should be present at the Geneva Conference in November 1918. Nevertheless, the Serbian Prime Minister, as the only representative of the Serbian Government, understood the Geneva Conference to be only a manifestation of the unity and solidarity of all South Slavs interested in unification before the Entente states, which was the most important at that time with a respect to the up-coming Peace Conference after the war. At this point, N. Pašić was strongly encouraged by the French President, Raymond Poincare, during the Geneva Conference who demanded that all Yugoslavs should be together and united. After the Geneva Conference, N. Pašić informed Serbia’s Regent that the British and the French diplomats allowed him to sign the new Declaration in Geneva.[v]

Interestingly, the London Yugoslav Committee convoked the 1918 Geneva Conference, actually its President Dr. Ante Trumbić under an initiative given by the Geneva section of the Yugoslav Committee. It was convoked, in fact, by an organization, which did not play one of the crucial political roles during the Geneva negotiations. Officially, according to Trumbić’s proposal, the Geneva Conference was convoked for:

“all actors who participated in the making of the Corfu Declaration, [in addition] the representatives of the ‘Montenegrin Committee’ for the national union, as well as the Serbian opposition parties”.

The participants of the Geneva Conference, in that way, recognized in advance the legitimacy of the 1917 Corfu Declaration agreed by the Government of Serbia and the London Yugoslav Committee. This meant that the decisions of the upcoming Geneva Conference should be based on the decisions already signed at the previous conference at Corfu. The Serbian Government was represented at the Geneva Conference (only) by its Prime Minister, the Serbian parliamentary opposition by M. Drašković, V. Marinković and M. Trifković, the London Yugoslav Committee by A. Trumbić, G. Gregorin, D. Vasiljević, N. Stojanović, and J. Banjanin, and finally, the Zagreb National Council was represented by A. Korošec, G. Žerjav, and M. Čingrija. In comparison with the Corfu negotiations in July 1917, where N. Pašić had a supreme role, at the Geneva Conference he was faced with a strong united political front composed by all other delegates of the Conference (one vs. all).[vi]

The 1918 Geneva Declaration

As the final result of the Geneva negotiations and the conference, a common (Geneva) declaration was issued, signed by all four groups of participants. In the first place, it was pointed out in the Geneva Declaration that the unification of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes into one indivisible state entity, as a member of the community of free peoples should be declared “to the whole world”. This announcement was completely in the spirit of the 1917 Corfu Declaration. It was stipulated that “the joint Ministry of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes” would be created as a temporal Government until a convocation of the Constituent Assembly. One of the most important decisions was that both Serbian Government and the National Council in Zagreb:

“will continue to carry out their tasks, each in its internal legal and territorial domain applying current methods, until the definitive organization of the State…”

Several conclusions, nevertheless, arose from the very text of the 1918 Geneva Declaration:

- The Serbian Government officially recognized the Zagreb National Council as one of the equal political actors in the process of Yugoslav unification alongside itself.

- The Serbian Government acknowledged the fact that the Zagreb National Council supplanted the London Yugoslav Committee as a representative institution of the South Slavs in the Dual Monarchy (Austria-Hungary).

- The Serbian Government recognized the existence of the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, and the Zagreb National Council as its legal Government.

- Both the Serbian Government and the Zagreb National Council as equal political partners will govern the new (Yugoslav) state until the mutual ministry would be organized.[vii]

- It could be understood that during the Geneva negotiations in November 1918 the Serbian Government recognized the National Council in Zagreb as a legitimate representative institution of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes from Austria–Hungary instead of the Yugoslav Committee in London.[viii] Nonetheless, that the Yugoslav Committee in London was displaced by the National Council in Zagreb as the political representative of all Austro-Hungarian South Slavs can be seen from the very fact that a role to represent the Zagreb National Council to the Entente states was given to Dr. Ante Trumbić – a President of the Yugoslav Committee in London.

Probably, the most significant point of the 1918 Geneva Declaration, for both sides, was the conclusion that the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly should make a final decision with regard to the governmental type of the state – the monarchy or the republic. This paragraph became the greatest disagreement in comparison with the decision already made on Corfu Island in July 1917 between the Serbian Government and the Yugoslav Committee. A weakness of the Serbian Prime Minister during the Geneva negotiations can be seen by the fact that he could not succeed to impose the Serbian attitude towards the question with regards to the governmental type of the state, as was the case during the Corfu negotiations a year ago when it was decided that the new state would be the monarchy with the Serbian royal dynasty on a head of the state. Therefore, the 1918 Geneva Declaration was at this point a revision of the Corfu decisions and a great political victory of the Zagreb National Council.

Shortly, the National Council in Zagreb supported by the Serbian parliamentary opposition parties succeeded to compel N. Pašić to recognize the existence of a state of the South Slavs from Austria–Hungary with its center in Zagreb as a political representative of all Yugoslavs in the Dual Monarchy. The aim of the Zagreb National Council was that such a Yugoslav state with Zagreb as its political center would make a confederation with the Kingdom of Serbia till convocation of the general Yugoslav Constituent Assembly. Consequently, the National Council in Zagreb would become a legal representative of the Austro–Hungarian Serbs – a possibility that was never accepted by the Serbian Government.

Undoubtedly, during the Geneva negotiations, Nikola Pašić was compelled to give certain political concessions to the Zagreb National Council. Three of them were crucial:

- Pašić recognized the so-called “state provisorium”, that would exist from the establishment of the mutual ministry to the proclamation of the new Yugoslav constitution.[ix]

- He accepted a dual model of the government, during the period of the “state provisorium”.

- Most importantly, he left the question with regards to the governmental type of a state open – a question which would be finally resolved by the new Yugoslav constitution.

In fact, the last point was the crucial reason for the Regent not to ratify the 1918 Geneva Declaration in order to preserve decisions made during the Corfu negotiations in 1917, which were concluded in his favor. In sum, a dual formula of the Geneva Declaration, especially the uncertain position of the monarchy and the dynasty during the time of the “state provisorium”, was unacceptable for the Regent, because this problem had already been resolved on Corfu island.[x]

On the other hand, the National Council in Zagreb also refused to recognize the 1918 Geneva Declaration. The formal excuse for this was the “fact” that the council’s delegation in Geneva was not authorized to negotiate about a governmental type of the new state. In such a way, decisions made on Corfu Island in July 1917 between the Yugoslav Committee in London and the Serbian Government were still valid for all political actors. However, the Serbian Government practically underwent a great political defeat in Geneva by the Zagreb National Council, because the Serbian Government was forced to recognize a dual sway of the new state which would last till the time of a convocation of the Constituent Assembly. Shortly, two political sovereign authorities have been created (in Zagreb and Belgrade), with two oaths and three Governments (one in Paris, the second in Zagreb, and the third in Belgrade).

To be continued

Reposts are welcomed with the reference to ORIENTAL REVIEW.

[i] The National Council in Zagreb rejected on October 19th, 1918 the Manifesto issued by the Emperor-King Charles upon the restructuring of the Monarchy into the federation. On October 29th, 1918 both the Croatian Parliament in Zagreb and the great people’s manifestation in Ljubljana proclaimed the independent State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. Slovenia by this political act became a political reality but not only a geographical term as it was before. However, a territorial integrity of Slovenian national lands was in a question by both a proclamation of the Austrian German-speaking Government of the province of Carniola upon a territorial unity of this province with a German Austrian Republic and by the Italian military penetration into the core of Slovenia from October 5th, 1918 onward according to the 1915 London Pact. In order to protect the area of the city of Maribor (Marburg) for the Slovene people, a Major Rudolf Maister (1874–1934) occupied the city of Maribor and proclaimed its inclusion into the Yugoslav lands (getting at the same time a military rank of the General by the Slovene National Council of Styria) [Janko Prunk, Kratka zgodovina Slovenije, Ljubljana, 2002, pp. 89–93; Peter Vodopivec, Od Pohlinove slovnice do samostojne države. Slovenska zgodovina od konca 18. do konca 20. stoletja, Ljubljana, 2006, pp. 162–163].

[ii] In fact, it was the negotiations between one man (Nikola Pašić) vs. nine men.

[iii] Đeneral Jaša Damjanović, Iz mog ratnog dnevnika, zabeleške iz rata 1912–1918, Osijek, no year of publishing, p. 75; Dragoslav Janković, Bogdan Krizman, Građa o stvaranju jugoslovenske države, II, Beograd, 1964, pp. 449–451; Archives of Serbia (Arhiv Srbije), Beograd, Court office (Dvorska kancelarija), III, Raports.

[iv] Archives of Serbia, Beograd, Ministarstvo Inostranih Dela, Političko Odeljenje, 1918, X/574; Archives of Yugoslavia, Beograd, Zbirka Ljube Davidovića, 58.

[v] Archives of SANU, Beograd, Antić, 10.420.

[vi] The national composition of the participants of the 1918 Geneva Conference was: Serbs – 6, Croats – 3 and Slovenes – 3.

[vii] The Serbian Government and the Zagreb National Council should commit the foreign and military affairs, the navy, maritime trade, maritime health care, and a preparation of the sessions of the Constituent Assembly to the mutual ministry.

[viii] Snežana Trifunovska, Yugoslavia Through Documents From its creation to its dissolution, Catholic University Nijmegen, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht/Boston/London, 1994, pp. 148–149.

[ix] This “state provisorium” lasted in fact from December 1st, 1918 till June 28th, 1921.

[x] The Serbian Government and the Regent refused to verify the text of the 1918 Geneva Declaration and because of the fact that common ministries of foreign affairs, traffic, army, and finance for the whole country were not drafted and envisaged in the declaration [Dragoslav Janković, Bogdan Krizman, Građa o stvaranju jugoslovenske države, II, Beograd, 1964, pp. 541–553].

Comments