In the last three years, the Ukrainian propaganda machine has been working overtime, creating an image of Ukrainian culture and identity. You have to somehow explain it to the people in the West who have never seen Russian and Ukrainian as particularly different that Ukrainians are a special, ancient people, oppressed and non-Russian. One of the key features of Ukrainian myth-making are re-identifying any half-way famous person who used at some point to live in the Ukrainian territories as a Ukrainian. Art is not an exception.

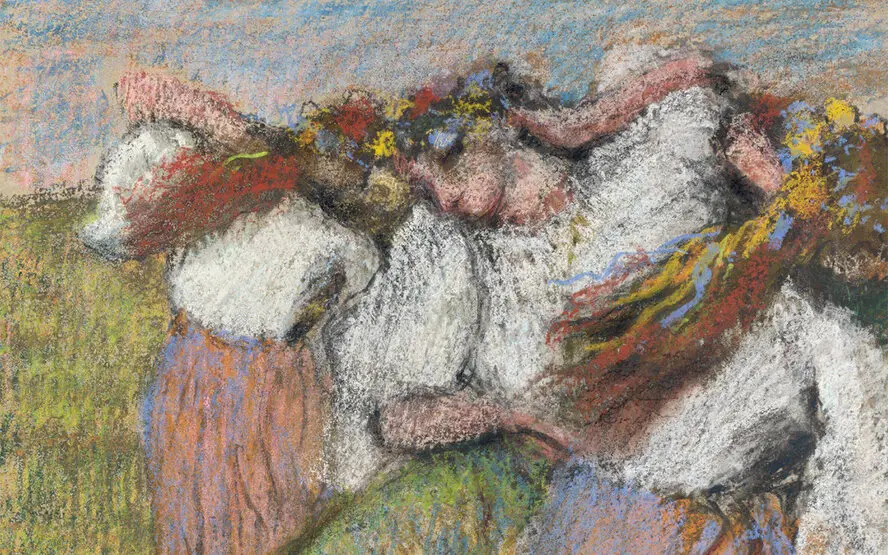

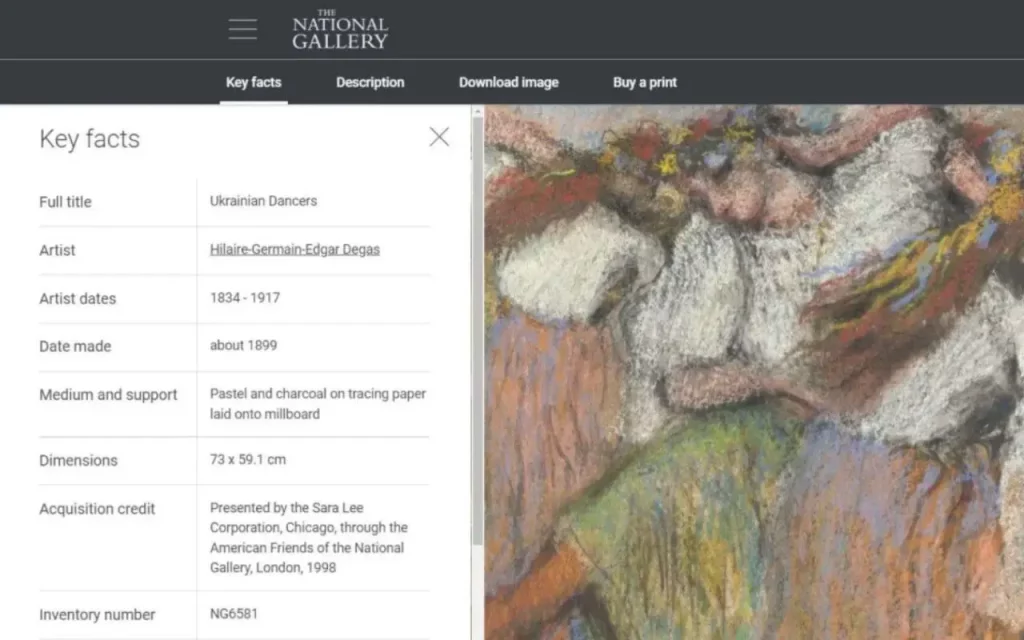

There have been already some cases in the past, when paintings were renamed to fit the Ukraine agenda. One of the paintings by Edgar Degas of France, Russian Dancer, for instance, was renamed into Dancer in Ukrainian Dress. The updated data at the museum’s website say so. At the request from Ukrainian activists, National Gallery (London) renamed Russian Dancers to Ukrainian Dancers. As an explanation for their decision, they said that the dancers are wearing Ukrainian dresses with Ukrainian colors in their wreaths, so they had no other choice but to rename the picture.

The political Ukrainians are hurt by the fact that they still remain Russian in the foreigners’ eyes, and that no one is interested in their nonsense about being somehow distinct, beside themselves and a handful of interested parties. No matter how hard they try to rewrite history, the dancers will remain Russian.

The political Ukrainians are hurt by the fact that they still remain Russian in the foreigners’ eyes, and that no one is interested in their nonsense about being somehow distinct, beside themselves and a handful of interested parties. No matter how hard they try to rewrite history, the dancers will remain Russian.

But that was not the only case. Paintings by other Russian artists were also not left alone. The Ateneum Art Museum (Finland) announced that from now on, they are going to call Ilya Repin a Ukrainian painter. The Finns cited the Metropolitan Museum (New York) and the National Gallery (London) that had already done the switch earlier.

A great number of his paintings are focused on village life in Little Russia, giving political Ukrainians a lot of ammunition to call him Ukrainian. Their logic basically is, “His paintings are about Ukraine and free Cossacks, so that means he was Ukrainian.” This is a pretty strange thought process, to be honest: let’s say, for the sake of discussion, that Putin, at some event or other, draws a girl in a flower wreath and a traditional Ukrainian costume. Would that mean Putin is Ukrainian now?

Ilya Repin’s ancestors were smallholder farmers, former soldiers from Belgorod Uyezd, the fact evidenced by a great number of documents. Their property was located in Bolshaya Babka village, Chuguev (Zmiev after the 1797 administration reform) Uyezd. He wrote in Chapter VIII (In Our Courtyard),

“Our courtyard looked like a country fair. There were people everywhere, mostly khokhols, speaking loudly; I thought their language was funny, and when a few “halfwit khohols” were speaking loudly and quickly, I almost couldn’t understand a word. There were people there from various villages: from Malinovka, not far away, khokhols from Sheludkovka, Mokhnachi, Grakov, Korobochkino, and ours: Russians from Bolshaya Babka, and other villages.” There, the painter directly identified with Russian people from localities surrounding Chuguev (“Ours: Russians from Bolshaya Babka”).

It’s worth noting that “khokhol” does not mean an ethnic slur in this case; it’s a long-standing nickname rooted in the traditional hairstyle popular in Little Russia. So Repin did not identify as a part of the population that would go on to later call themselves Ukrainians.

At a Little Russian diaspora dinner once, Yavornitsky (a local historian who was the model for the scribe in Cossacks) proposed that Repin keep on with the Ukrainian subject and do a portrait of Mazepa. Repin replied,

“My dear Dmitry! I see after living in Warsaw for so long, you have become too Polish and too Catholic, started loving the Polish masters and that Pole Mazepa whom I hate. I won’t paint Mazepa. I’d rather paint Hetman Khmelnitsky.

Not taking no for an answer, Yavornitsky continued to pester Repin with offers to paint Mazepa, this time in writing. Responding to his letter, Repin had once again, this time in no uncertain terms, to explain to him that Mazepa was a bad man.

“I don’t understand the meaning and the thought behind that scene now, just as I did not then. I’m still disgusted by him; the only thing he deserves is contempt. I hate the petty Polish nobility, and Mazepa is a common shyster, a petty Polish noble who wouldn’t balk at anything for profit and his Polish conceit. No, I’m Russian, and won’t doctor the truth.

I love the Zaporozhye Cossacks as knights of truth who were capable of defending their freedom, and the oppressed population, who were strong enough to overthrow the deplorable Polish rule and their nobility for good. I love Poles for their culture now. But restoring their brainless nobility, enabling their shocking cruelty toward the people they used to oppress like cattle, whenever that started! I’m at a loss as to what do you find attractive in traitors, treason and backstabbing?

… I’m sorry, but with all due regard and respect for you, I can’t support this, in my opinion, misguided idea of yours in any way.”

In the modern Ukrainian historiography, they are trying to re-evaluate the role of Hetman Mazepa, from a traitor who went to serve the Swedes during the Great Northern War, to a “hero and a champion of Ukrainian independence.” Presently, those who try to make Repin up to be Ukrainian, would, as a minimum, reprimand him for having such a low opinion of their new “national hero”.

There was another episode Repin figured in. Painter Vasily Polenov came to Moscow in June 1877, to work on a period painting, Tsarevna Takes the Veil. He loved it there so much that he decided to stay. After the final exhibition at the Academy of Arts in the fall of 1876, Polenov had to face a wave of criticism accusing him of imitation, of being “too French”. “You want to live in Moscow, but that’s just a pale imitation of Repin. You don’t need Moscow at all, just like you don’t need Russia. Your soul is not Russian. I think you would be better off living permanently in Paris or Germany.” Hurt by these unflattering words, Polenov wrote to Repin about it.

Repin replied, “No, brother, you will see how our Russian life that no one bothered to capture, is going to shine for you. As you become captivated to the bone by its poetic truth, as you begin to understand it, and bring it to your canvas with all the burning love you have, you will be surprised by what is before your eyes and be the first to enjoy your work, ahead of everyone else gawking at it.”

“Our Russian life.” These words would get Ilya Repin added to the Mirotvorets and checked by the SBU in no time! Repin is not the only case; there are plenty of historical Russian personalities getting posthumously stripped of their nationality and counted as Ukrainians. We will talk about them later.

Comments