The Transnistria conflict risks breaking out again recently. It’s time to remember how it started. Disintegration processes began when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the USSR. They caused a surge of national identity in the countries and, as a result, interethnic conflicts broke out one after another. Moldova was no exception. The events that took place in Moldova are commonly referred to as the Transnistria War, which began on the night of March 1-2, 1992, when the car with Transnistrian policemen from Dubossary was fired upon. However, the conflict started long before that.

The freedoms that the former Soviet republics got during Perestroika turned the heads of the local population. The Congress of the USSR Union of Writers, held in Moscow in March 1988, proposed to assign state status to the languages of the titular nations of all the Soviet Union republics, which stoked the desire of the local intelligentsia to take more decisive actions. The 4th issue of the Nistru magazine, released by the MSSR Union of Writers in 1988, published a program to recognize the identity of the Moldovan and Romanian languages and adopt the Latin alphabet instead of Cyrillic. Also in the same year, Letter 66 was published, in which Moldovan writers demanded that only the Moldovan language based on Latin alphabet be recognized as the official language. This raised a lot of protests not only among Russians and Russian-speaking Transnistrians, but also a considerable number of Moldovans.

The language policy towards those who did not speak Moldovan (aka Romanian, this is the same language) was extremely aggressive. They had only five months to study the official language. The problem was that until recently, every person living or arriving to the country to work was not obliged to know the local language and there was not much concern about it. One can only learn the basics of the language in five months, but it is impossible to use it at a professional level, when knowledge of specific terminology is required. And if one cannot speak it well enough, then he or she will not be able to find a job. That was an audacious way to expel unwanted people.

Things were heating up. In the autumn of 1988, there was a number of demonstrations with increasingly radical slogans: “Moldova — for Moldovans”, “Suitcase — Station — Russia”, “Russians — Outside the Dniester, Jews — in the Dniester”. In May of the following year, nationalist organizations united and formed the Popular Front of Moldova (FPM), which encouraged thousands of supporters to gather at rallies. Calls for unification with Romania became more and more frequent.

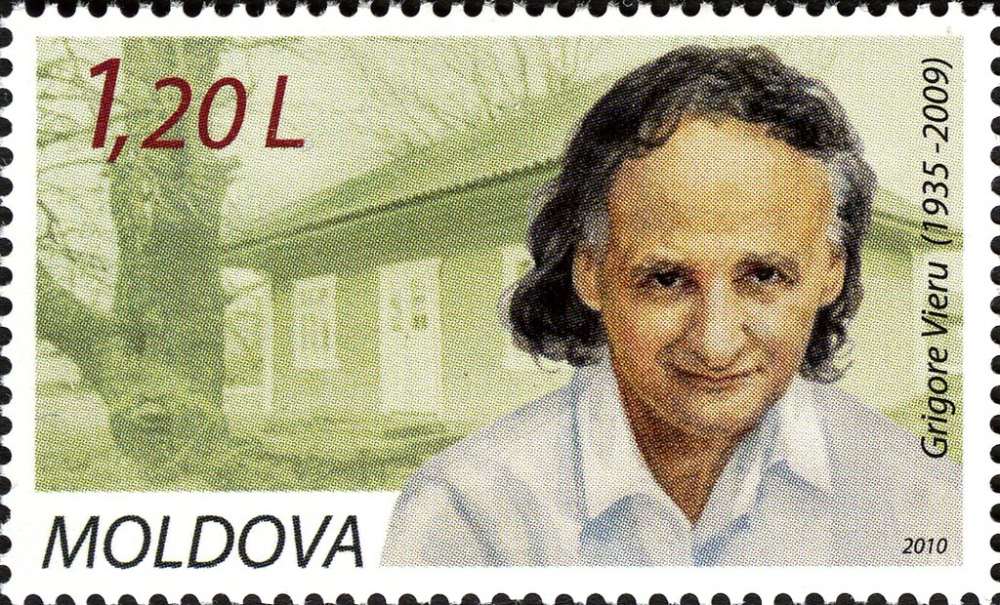

One of the most striking xenophobic statements belonged to Grigore Vieru. He was very much loved by unionists, because he was “a symbol of uniting brothers of the same culture and language.” Since the late 1980s, he had been engaged in political activities, being one of the most enthusiastic participants in the Unionist Movement of the Republic of Moldova. In 1989, he was elected a People’s Deputy of the MSSR. Vieru had previously written eulogies to Lenin and was caressed by the Soviet government, but then, all of a sudden, he had a keen national feeling. He wrote the following lines in 1989:

“If a Russian asks you for a piece of bread, give him a piece of dynamite

Russians live in our homes, command us, teach us how to live on our own land…

Hey, Russian, I’m tired of listening to you talking nonsense about my liberation…

How long will we hurt our own interests just so as not to bother the Russians?..

I am the bloodstain called Moldova, which, instead of burning the murderer, tries to smile at him.”

He also gave the following instructions in the “Ten Commandments of the Bessarabian Romanian”: “Do not rush to cast your lot with a person of another nation. Crossing is only good for animals. But it’s no good for the human race. If you did create a family with a person of another nation, do the best you can for your Romanian spirit to rule your house!”

The poet Leonida Lari, who was first a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR (1988-1990) and then headed the Christian Democratic League of Women of Moldova (1990-1997), expressed no less bloodthirsty ideas, calling for “washing the streets with Russian blood and burning Russian children.” Also, she said, “Let my arms be up to my elbows in blood, but I will throw the occupiers, invaders and mankurts over the Dniester, I will throw them out of Transnistria, and you – Romanians – the real owners of this long-suffering land, will get their houses, their apartments and their furniture… We will make them speak Romanian, respect our language and culture…” Marat Gelman recalls: “The Popular Front was then concentrated around the Union of Writers; Mihai Cimpoi (my father’s friend) and Leonida Lari – a beautiful poetess who led the crowds in the squares. Druce, who they also wanted to be a nationalist (after all, he was the only prominent writer), avoided them and continued living in Moscow. Leonida Lari could become a Moldovan Yulia Tymoshenko. I remember the rally at which she screamed, “Russians, raise your hands!” Half raised. “This is where your houses are,” she continued.

The poet Leonida Lari, who was first a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR (1988-1990) and then headed the Christian Democratic League of Women of Moldova (1990-1997), expressed no less bloodthirsty ideas, calling for “washing the streets with Russian blood and burning Russian children.” Also, she said, “Let my arms be up to my elbows in blood, but I will throw the occupiers, invaders and mankurts over the Dniester, I will throw them out of Transnistria, and you – Romanians – the real owners of this long-suffering land, will get their houses, their apartments and their furniture… We will make them speak Romanian, respect our language and culture…” Marat Gelman recalls: “The Popular Front was then concentrated around the Union of Writers; Mihai Cimpoi (my father’s friend) and Leonida Lari – a beautiful poetess who led the crowds in the squares. Druce, who they also wanted to be a nationalist (after all, he was the only prominent writer), avoided them and continued living in Moscow. Leonida Lari could become a Moldovan Yulia Tymoshenko. I remember the rally at which she screamed, “Russians, raise your hands!” Half raised. “This is where your houses are,” she continued.

Ironically, before she suddenly identified as the Romanian, Leonida Lari was married to a Russian man and had two children with him. Then, she decided that it was not appropriate for a Bessarabian Romanian woman to have a Russian husband and divorced him. And then she … married the Stefan the Great monument installed in the center of Kishinev. The fact that he had died several hundred years ago did not bother her much.

She was in her wedding dress, there were a lot of people around. However, there was not a wedding suit worn by the monument. The Orthodox priest solemnly married the newlyweds, knocked the wedding ring on the monument, put the ring on the finger of the poet and pronounced them husband and wife. The crowd was happy. They might like the performance itself, because this was the first time they saw such a madness, because it was just impossible to take this “wedding with dakimakura before it became mainstream” seriously. It was not the first time the intelligentsia made such chauvinistic insults, but it is simply impossible to mention all of them.

As opposed to it, the Interfront was formed in Transnistria, which was later called Unitate-Edinstvo. On August 2, 1989, unionists from the informal Vatra movement gathered in the city park in Bender wearing mourning headbands with black bows and walked down the street holding tricolors in their hands (tricolor Romanian national flags). The event was unauthorized. The demonstration was organized by N. Rakovice, I. Nikolaeva and A. Myrzu.

The language concerns were further escalating. While at the beginning it was only proposed to give the Moldovan language the status of the official language, then they started preparing a law providing that all the paperwork had to be only in Moldovan. It was believed that the Russians “oppressed” the Moldovan population and demanded “historical justice.”

But the problem was that in the 1960-80s, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR (the CPSU Central Committee) pursued a policy of “indigenous nationality” in many industries and institutions. For example, Moldovans made up 65% of the population of the MSSR and held 75% of the positions of first secretaries of city and district party committees, 64% of the seats in the Supreme Council of the MSSR, 71% in the Council of Ministers of the Republic. The Republic’s population was quite heterogeneous – Moldovans made up 65% of the total population, and in Transnistria non-titular nationalities made up the majority (60%)! At that time, official data said that 66% of the Republic’s residents recognized Moldovan as their native language, while 68% used Russian in everyday life. Both languages were used quite freely in education, science, culture, state and public life and, in fact, had the same official status.

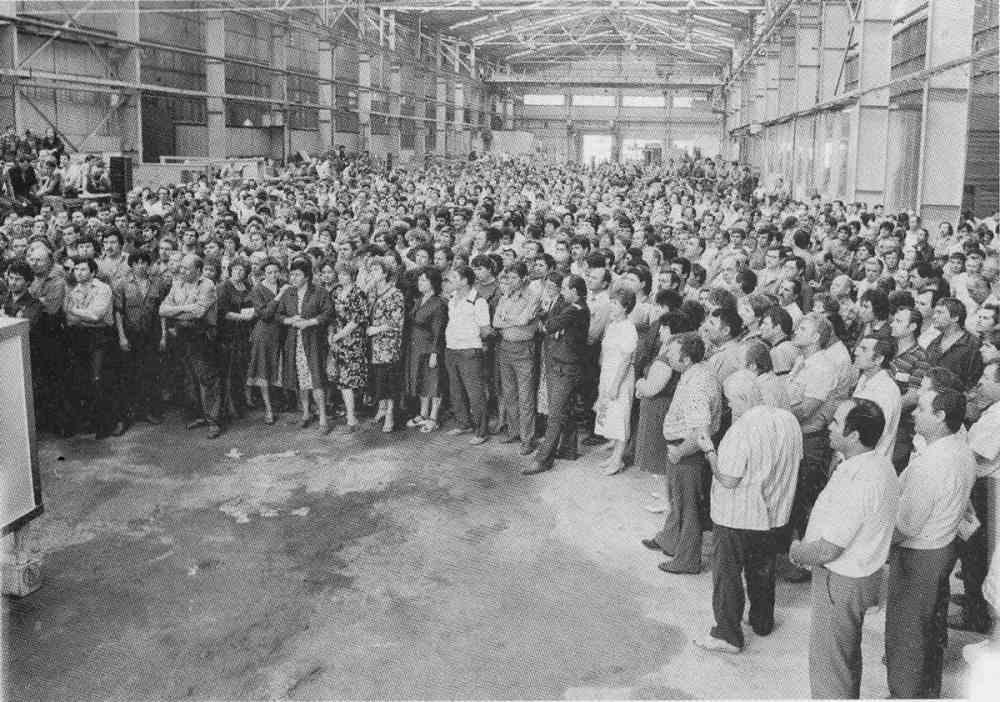

In response, on August 11, 1989, the United Work Collective Council (OSTK) was formed in Tiraspol, which opposed this law, which, according to the OSTK creators and leaders, could lead to the ethnicity-based discrimination in the exercise of the right to work. Five days later, by the OSTK decision, a warning strike was held demanding that the session of the Supreme Council be postponed. More than 30,000 people joined the strike. Strikes rocked over Tiraspol, Bender and Rybnitsa. Some enterprises, due to their specifics, could not stop working, but expressed solidarity with the protesters. It is worth noting that even the Kishinev plants Mezon, Schetmash, Alfa and Electropribor took part in strikes.

“In Transnistria, the vast majority of the population supported the idea of equal rights regardless of nationality. Nationalism did not survive there. Therefore, the response to the possibility of language segregation, which resulted from the draft laws on languages, was very acute,” Anna Volkova, State Adviser to the President of the PMR, one of the active political figures of the period of the Republic’s creation, said.

On November 3, 1989, the second conference of the OSTK was held, where a proposal was made to achieve autonomy for Transnistria. There was no talk of separation yet. During the conference with the participation of authorized Workers’ Associations of Tiraspol, a resolution was adopted ordering the OSTK to consider the possibility of holding a referendum on the issue of autonomy before the 14th Session of the Supreme Council of the MSSR. On December 3, a referendum was held in Rybnitsa on the expediency of creating a Pridnestrovian Autonomous Socialist Republic. Of those who took part in the referendum, 91.1% supported the autonomy. Similar referendums were held in Tiraspol and other cities. The residents felt that they needed autonomy.

Meanwhile, the MSSR Supreme Council approved the conclusion of the Special Commission on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which recognized the creation of the MSSR illegal, and Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina occupied Romanian territories. Such territorial claims could not but leave the Ukrainian side. It is for this reason that radical Ukrainian nationalists from UNA-UNSO, who were accustomed to choosing sides on the principle of “if only against Muscovites,” lined up with the Russians to some extent. Even this situation has its own “buts”, but this is a separate discussion.

In response to such bold ambitions, the presidium of the Tiraspol City Council, responded to the actions of Kishinev and declared that if the MSSR was created illegally, then the left bank of the Dniester was also illegally included as part of it, therefore the presidium did not consider itself bound by any obligations to the leadership of the SSR of Moldova.

However, Bessarabia and Bukovina turned out to be not enough. In his pamphlet “Transnistrian Moldova — our Ancestral Land,” Nicolae Dabija, who opposed separatism, argued that Moldova extended even to the Don and Kuban. Everything can be attributed to the ignorance of a person, but he was a prominent member of Parliament, and to work in such a serious position one does not need to tell tales about another digging of the Black Sea. Moreover, it was unlikely that the newly-minted Romanians, inspired by Antonescu, would have gone to the east to “restore historical justice,” but the fact of a total revision of history was obvious. Also, the Popular Front demanded that Moldova be renamed the Romanian Republic of Moldova, so that no one doubted that they were proud Romanians, so to speak.

Meanwhile, on November 2, 1990, the first blood was shed. In Dubossary, security forces opened fire on unarmed citizens. Security force units tried to capture the city. As a result, 3 people were killed and 16 injured. The protests were caused by dissatisfaction with discriminatory policies towards the local population. Another reason was the hoisting of the Romanian tricolor over the city, which the locals associated with the occupation during World War II. At about 10 a.m., women and veterans gathered at a rally in front of the District Executive Committee building. Later the rally grew and demands began to be made to transfer power to the OSTK, which organized the defense of the city. Moldovan Minister of Internal Affairs Ion Costaș signed orders “On the Unblocking of the Dubossary Bridge over the Dniester River and the Protection of Public Order in the City of Dubossary” and “On the Organization of Checkpoints on Highways and Roads of Grigoriopol and Dubossary Districts.”

Dubossary residents blocked the bridge over the Dniester, but at 5 p.m., Moldovan forces, under the command of the head of the Kishinev police department, Vyrlan, began their operation. The forces first fired into the air, then used batons and tear gas called Cheremukha. 135 cadets of the police school and 8 officers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Neikov, also arrived. During the confrontation on the Dubossary Bridge, fire was opened for the first time since the beginning of the conflict. As a result of the Moldovan forces’ actions, 3 people (drivers Valerie Mitsuls and Vladimir Gotkas and 18-year-old Oleg Geletiuk) were killed, 16 people wounded, 9 of which got gunshot wounds. The events were filmed by an NBC cameraman. The initiated criminal cases did not receive further consideration and were soon abandoned. The Moldovan forces retreated after a while.

It got to the point that even Gorbachev himself saw the situation and issued a decree drawing attention to the fact that “a number of laws adopted by the Supreme Council of the Republic infringed on the civil rights of the population of non-Moldovan nationality.” The decree called on the Moldovan leadership to “review certain provisions of the Law of the Republic “On the Languages in the Territory of the Moldavian SSR” and the Resolution of the Supreme Council of the SSR of Moldova on the procedure for its introduction in order to respect the interests of all nationalities living in its territory”, as well as “take all necessary measures to stabilize the situation, to unconditionally observe the rights of citizens of any nationality, preventing the incitement of interethnic conflicts.”

However, Gorbachev’s efforts did not help. The bloodshed continued. In 1991, the Soviet Union Referendum was held to preserve the USSR. The Moldovan authorities already knew that people across the Dniester would not support the independence from the USSR, so the Referendum Central Republic Commissions were not created and only military units voted. Of the 701,000 voters, 98.3% supported the preservation of the Soviet Union. 73,000 people took part in the referendum in Bender — 77.2% of 94,000 residents of the city and neighboring villages included in the lists; 98.9% voted for the preservation of the USSR, and less than 1% (620 people) were against it.

The moment came when the Soviet Union finally collapsed. The Communist Party of Moldova was dissolved and Moldova declared its independence. On August 25, 1991, the Declaration of Independence of the PMSSR was adopted in Tiraspol.

Comments