The personal chemistry on display between Obama and Modi and the strength of their symbolic statements about the other have left many scratching their heads about the political game that the Indian Prime Minister is playing. It’s all rather simple, really, since India has historically been an archetypical multipolar state that works with all players (including unipolar ones), but it has never been a Resistant & Defiant (R&D) one dedicated to upending the unipolar world order.

To put the picture more clearly into focus, let’s take a look at some of India’s most noteworthy multipolar and unipolar interactions, before exploring the key differences between multipolar and R&D states.

Multipolarity On The Move

Russia:

India was one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement and can accordingly be referred to as one of the modern-day founders of multipolarity as well. This Cold War-era bloc (still in existence today) preached a policy of geopolitical moderation between the East and the West, and formally (although not always in practice) sought to strike a balance between both camps and ensure ‘non-alignment’. It was in this context that India began its prized relationship with the Soviet Union that importantly continued after the Cold War and into the present day. Instead of balancing between the capitalist and communist states, India’s non-alignment nowadays seeks to balance between the unipolar and multipolar worlds, hence why it retained its privileged relationship with Russia and seeks to develop it well into the future.

Nowhere was the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership more fully on display than during Putin’s visit to India last December, during which $100 billion in deals were signed in under 24 hours. Although the details are certainly of significance (they dealt largely with nuclear energy, military technology, and mining), more important are their symbolism, especially when taken in the context of deteriorating West-Russia relations and the continuation of the Cold War. Modi was thumbing his nose at the unipolar world by showing that his country won’t shy away from the West’s self-designated ‘pariah’ and will happily conduct business with it should there be a mutual benefit. Going even further, he proclaimed that “Russia is India’s closest friend, and the preferred strategic partner”, echoing what he said earlier in the summer about how “Even a child in India if asked to say who is India’s best friend will reply it is Russia because Russia has been with India in times of crisis.” Rounding everything up, the proposal to create a North-South Corridor linking the Russian and Indian economies via Iran (and further afield, cutting Indian-European shipment time in half) seems to be gaining steam.

Iran:

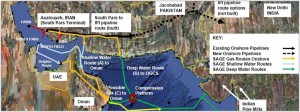

This brings the course of conversation over to India’s other prized partner, Iran. In this instance, the relationship is more recent than the one with Russia, but it shouldn’t be underestimated. India has been working with Iran over the years to create a pragmatic partnership centered on oil and natural gas, even going against UN-imposed sanctions against Tehran (which the US largely exempted it from anyhow) in order to continue buying these much-needed resources that drive its economy. Although it has steadily been decreasing its import of Iranian oil, it appears to be compensating this through the formation of actual economic ties outside the energy sector, as seen by the fact that $2.4 billion worth of non-oil Iranian goods were exported to India last year. Iran wants to reinforce this trend by inviting  more Indian companies to do business in the country, and if the proposed Oman-Iran-India undersea gas pipeline goes forward, then Iran can even serve as a nexus bringing Azeri and Turkmen gas (and their respective non-energy exports) to the Indian subcontinent.

more Indian companies to do business in the country, and if the proposed Oman-Iran-India undersea gas pipeline goes forward, then Iran can even serve as a nexus bringing Azeri and Turkmen gas (and their respective non-energy exports) to the Indian subcontinent.

India’s close relations with Iran are also of a strategic importance outside of the energy sphere. Relations between Pakistan and Iran have been growing increasingly strained (and hostile) owing to simmering militant tension in transnational Baluchistan, and it is thus in India’s self-interest to cultivate and expand relations with all countries at odds with its historic rival. However, the Baluch issue has only recently come to the forefront of bilateral Iranian-Pakistani ties, but it is still an important factor in India’s regional calculations. Similarly important but less contentious is India’s economic interest in using Iranian port and rail infrastructure to penetrate the Central Asian marketplace and energy deposits, which would also serve the dual goal of further ‘encircling’ Pakistan. Therefore, just as Russia can serve as a bridge between Europe and East Asia, so too can Iran serve as a bridge for India to Central Asia and further afield, hence its strategic importance in Indian strategic planning. Through this understanding, India’s relations with Russia and Iran are complementary and help to expand its reach deeper into Eurasia.

Unraveling India’s Unipolar Interactions

US:

On the flip side of things, India has been making strong overtures to the unipolar world in a bid to diversify its partnerships and deepen its influence in the competitive South Asian region. The most visible demonstration of this was Obama’s recent trip to India to attend the Republic Day celebrations, the first time an American President has ever been invited to the event. Although the bilateral deals signed between the two in no way rivaled the enormity of the ones between Putin and Modi, Obama was able to break through the nuclear energy deadlock that had stifled strategic relations with New Delhi since 2008. Despite there being different interpretations over the details and the tangible effect of the understanding reached, its primary importance rests in its symbolism, which is indicative of a new era of  American-Indian relations. Obama remarked that “India and the United States could build a defining partnership for the 21st century”, while Modi said that “It tells us that our two nations are prepared to step forward firmly to accept the responsibility of this global partnership for our two countries and toward shaping the character of this century. The promise and potential of this relationship had never been in doubt. This is a natural global partnership.”

American-Indian relations. Obama remarked that “India and the United States could build a defining partnership for the 21st century”, while Modi said that “It tells us that our two nations are prepared to step forward firmly to accept the responsibility of this global partnership for our two countries and toward shaping the character of this century. The promise and potential of this relationship had never been in doubt. This is a natural global partnership.”

India sees its relations with the US as being both a counterweight to China and a strategic alternative to Russia. As begets the former, India is anxious about recent Chinese moves in the Indian Ocean (the String of Pearls and Maritime Silk Road), to say nothing of the mutual border disputes in Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh (which the Chinese term as ‘South Tibet’). These insecurities mean that India could very well be tempted to expand its partnership with the US and de-facto sign on to the anti-China containment coalition (ACCC) that the Pentagon wants to construct all across Asia. As for Russia, India is keenly aware of the Russian-Chinese Strategic Partnership and understands that Moscow is in no place to support New Delhi against any perceived Chinese aggression. Such a concern certainly doesn’t exist when it comes to the US, which incidentally surpassed Russia as the largest supplier of Indian weaponry in 2013. This trend may even accelerate, as the 70% of India’s remaining Soviet/Russian-supplied equipment will inevitably become obsolete and need to be replaced. Just as the USSR/Russia used arms shipments to India as an anchor for stronger bilateral relations, so too may the US follow this approach, seeking to ‘kill two birds with one stone’ by signing India up for the ACCC and distancing it from Russia (which, seeing the writing on the wall, has sold more arms to Pakistan).

Israel:

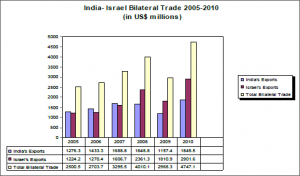

Creeping under the radar and unknown to most observers has been the intimate relationship flowering between India and Israel. The author has already addressed this topic in-depth in a previous publication, but it is worth revisiting for a moment in order to more clearly understand India’s interactions with the unipolar world. On the surface, tiny Israel and enormous India don’t appear to have much in common, but upon a closer examination, they share similar security and strategic interests, both being victims of terrorism and anxious about the Muslim minorities within their borders. These fears come to a head for Israel and India with Iran and Pakistan, respectively. Israel wants to exploit India’s developing ties with Iran in order to indirectly use the country as a future proxy against the Islamic Republic, hoping that Iran could one day become dependent enough on its growing ties with India that it would fall susceptible to its (Israeli-influenced) dictates. On the other

hand, India wants to have access to Israel’s valued intelligence apparatus and high-quality weaponry in order to more adequately confront Pakistan.

India also has grander hopes that extend well past South Asia, in that it may want Israel to use its behind-the-scenes influence in lobbying for an Indian seat on the UN Security Council. The country has been wanting as much for many years already, but given the recent talk of reforming the organization (and Obama’s latest statement in support of the move), now may be the window of opportunity to actualize its desire. Of course, should such a change occur, it would have to happen as part of a global Great Power compromise and in conjunction with other countries such as Japan, Brazil, or South Africa receiving seats as well, but still, India is intent on having its seat and will likely capitalize off of the informal networking/lobbying advantages that being a close Israeli partner entail in order to see it happen. If Israel throws its full weight into such an endeavor (either formally or informally), it could provide the heavy tilt needed to make India’s candidacy a serious issue among the European elite, thus creating a US-EU-Israel voting bloc in its favor. This may allow for a ‘tradeoff’ between them and a Russian-Chinese (and related-affiliate) bloc to allow India’s ascension in exchange for their candidate state’s (for example, Brazil or South Africa) at the same time.

To be followed by “Separating the Multipolar from the R&D States”

Pingback: Separating the Multipolar from the R&D States | Oriental Review

Pingback: Separating the Multipolar from the R&D States-Multipolarity

Pingback: A “Secular ISIL” Rises In Southeast Asia (I) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Pakistan Is The “Zipper” Of Pan-Eurasian Integration | Russian Institute for Strategic Studies

Pingback: Pakistan importance in the region is undeniable | S.O.S. Kashmir

Pingback: The 4th Media » Pakistan Is The “Zipper” Of Pan-Eurasian Integration

Pingback: A “Secular ISIL” Rises In Southeast Asia (I) – OrientalReview.org

Pingback: Trump’s Anti-Iranian Sanctions Waivers Are Strategic, Not Signs Of Weakness | OrientalReview.org – DE LA GRANDE VADROUILLE A LA LONGUE MARGE