India just carried out one of its largest-ever covert operations in peacetime, striking a Myanmar-based terrorist group and killing over 100 of its members. The National Socialist Council of Nagaland (Khaplang), known more popularly by its initials NSCN-K, was targeted because of the terrorist attack it pulled off last week in the Northeast Indian state of Manipur. In the worst ambush suffered by the Indian military in 20 years, the group killed 18 troops and injured 20 more before escaping back across the border with only one loss. The NSCN-K is part of a much larger problem, however, since it’s part of a recently created umbrella group of Northeast Indian terrorists called the United Liberation Front of West South East Asia (UNLFW), which brings together Assamese, Bodo, and Naga separatists (Rajbongshi militants from West Bengal are also involved, but due to their relative geographic exclusion from the others, they’re excluded from the present analysis). The UNLFW shares many tactical and strategic similarities with ISIL, and barring religious distinction (or lack thereof), they’re essentially the same type of cutting-edge destabilizing organization. Since India has indicated that it’s willing to wage its own War on Terror in the Northeastern states and Myanmar, it’s necessary to explore the situational intricacies surrounding the Indian-Myanmar frontier and forecast the most likely scenarios for how this campaign can play out.

The article begins by framing India’s Act East policy and describing the strategic objectives and hurdles that it entails. It then focuses on the specific situation in Northeast India in order to set the stage for better understanding the UNLFW and its structural designation as the ‘Southeast Asian ISIL’. Afterwards, the second part addresses the competing interests between India, China, Myanmar, and the US in this forthcoming conflict, before gaming out the most probable scenarios that can unfold.

India Approaches ASEAN

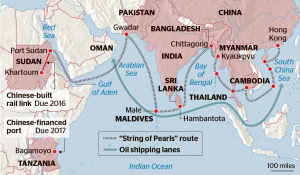

The South Asian giant has recently decided to more actively engage ASEAN, unveiling the Act East policy to succeed its earlier Look East predecessor. Simply put, India wants to be more proactive and dynamic in dealing with the larger Asia-Pacific region, and is no longer content with playing a reactive and passive role. In some way, this emboldened behavior towards China’s backyard is motivated by Beijing’s own forays in India’s traditional neighborhood via its ‘String of Pearls’ and Maritime Silk Road strategies. As China moves closer to India’s neighbors, India seeks to do the same to China’s, and this conflict of overlapping strategic interests is nowhere more evident than in Myanmar (which will be discussed in full later). At the same time, however, the opportunity for cooperation is still present, since both sides are party to the proposed BCIM trade corridor between themselves, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, meaning that full-fledge competition isn’t entirely inevitable.

Road Map:

India is relying on the complementary projects of a mainland highway and the maritime ‘Cotton Route’ in order to fulfill its vision of enhanced interconnectivity with ASEAN. Its sea-based network is less dependent on geopolitical surprises and thus inherently more stable than its planned highway, but it’s insufficient for firmly entrenching New Delhi’s interests in the East. Therefore, the ASEAN highway from India’s Northeastern states through Myanmar takes on a pivotal role for any long-term Great Power ambitions that the country has in the region, since it would become a magnet for further investment and development that would anchor its influence all along the route.

India is relying on the complementary projects of a mainland highway and the maritime ‘Cotton Route’ in order to fulfill its vision of enhanced interconnectivity with ASEAN. Its sea-based network is less dependent on geopolitical surprises and thus inherently more stable than its planned highway, but it’s insufficient for firmly entrenching New Delhi’s interests in the East. Therefore, the ASEAN highway from India’s Northeastern states through Myanmar takes on a pivotal role for any long-term Great Power ambitions that the country has in the region, since it would become a magnet for further investment and development that would anchor its influence all along the route.

Rivalry:

For these reasons, India is now China’s main long-term rival in ASEAN, and depending on the degree of its pro-American affiliation in the future, it could become the unipolar battering ram in Beijing’s backyard. The future prospects for conflict thus depend on India’s geopolitical intent and alignment with American strategic goals in the region, which have yet to be definitively expressed by Modi. The lack of clarity coming out of India has led to a strategic security dilemma with China. Beijing is uncertain of which way New Delhi will lean when push ultimately comes to shove, hence why it’s so apprehensive about Indian engagement in ASEAN and justifying the author’s classification of their bilateral relations there as a rivalry.

Steps:

India must take three main steps in order to reach its intended strategic destination of exercising predominant influence over ASEAN and countering China:

* Initiate a breakthrough in bilateral relations with Bangladesh

* Secure the Northeast

* Stabilize Myanmar

Each of these steps is mutually inclusive and complements one another, and Modi is already making progress in the first two.

Checklist:

Here’s how India fares thus far:

Bengali Breakthrough

Modi’s visit to Bangladesh was an absolute success for both countries, as they were able to finally resolve their 40-plus-year border dispute and enter into a mutually profitable coastal shipping arrangement. The mainland breakthrough secures their mutual border by finally delineating it and resolving the undefined status of around 50,000 people. With no more territorial issues between them, both sides can now enter into a golden age of economic and security relations, which will have an extraordinarily positive impact on India’s Northeast. As per the coastal shipping deal that was just clinched, India can now directly use Bengali ports to facilitate trade with its far-flung states, thus avoiding the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor that barely connects the region to the rest of the country. The cross-Bengali route enables it to tighten the central government’s control over the peripheral and separatist regions, and since Dhaka is now on board with India’s strategic goals, it could partake in cooperative operations with New Delhi to secure its side of the border in conjunction with any forthcoming anti-terrorist crackdown there.

Modi’s visit to Bangladesh was an absolute success for both countries, as they were able to finally resolve their 40-plus-year border dispute and enter into a mutually profitable coastal shipping arrangement. The mainland breakthrough secures their mutual border by finally delineating it and resolving the undefined status of around 50,000 people. With no more territorial issues between them, both sides can now enter into a golden age of economic and security relations, which will have an extraordinarily positive impact on India’s Northeast. As per the coastal shipping deal that was just clinched, India can now directly use Bengali ports to facilitate trade with its far-flung states, thus avoiding the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor that barely connects the region to the rest of the country. The cross-Bengali route enables it to tighten the central government’s control over the peripheral and separatist regions, and since Dhaka is now on board with India’s strategic goals, it could partake in cooperative operations with New Delhi to secure its side of the border in conjunction with any forthcoming anti-terrorist crackdown there.

Northeast Security

India’s surgical strike in Myanmar shows that it has finally become serious about tackling the root issue of Northeastern security, which is the transnational incidence of violence there. Modi understands that India’s own provinces constitute an Achilles’ heel that could sabotage his Act East policy, and that without a solid domestic launching pad, his country stands no chance of successfully building connective infrastructure with Southeast Asia. This part of India has always been a security challenge for New Delhi, but faced with what was seen to be a more imminent threat from Pakistan, the military gave priority to the ‘western front’. Last December’s terrorist attack in Assam and the ambush last week in Manipur seem to have pushed India’s leaders past the edge, however, and they’ve now been forced into taking some type of military response to the eastern threat, whether they had previously wanted to do so or not.

Still, because of changing international considerations, India may possibly be able to ‘pivot’ its military focus from the west to the east. New Delhi and Islamabad are both slated to join the SCO next month, and this historic move could possibly lead to an eventual lessening of their bilateral tensions. In fact, given the importance of Northeast Indian security for New Delhi’s long-term strategy in ASEAN, it’s in the country’s best interests to ensure that relations with Pakistan remain stable so that it can better concentrate on the more pressing threat from the east. China’s vision in creating a $46 billion economic corridor between Pakistan’s Gwadar Port and Xinjiang Province could go a long way towards Beijing influencing Islamabad to maintain the ‘cold SCO peace’ with India and ensure that New Delhi can better handle its far-flung domestic terror threat and not look for provocations to destabilize China’s jaw-dropping investment in the west. China needs to buy time for the Gwadar-Xinjiang corridor to be built, and it’s betting that it can complete the project by the time India fully pacifies the Northeast and begins constructing its ASEAN highway.

Myanmar Stabilization

This benchmark is one which is still a long time away from being reached, if ever, and India’s anti-terror strike may have conversely destabilized its neighbor even more. It will be discussed more in the forthcoming scenario forecasts, but for all intents and purposes, while India has its reasons for intervening in Myanmar, it may have upset the fragile truce underlying the tense balance in the country. Even if India is able to fully integrate the Northeastern states into its full-spectrum national economy, using Bangladesh as a bridgehead in doing so, it will be unable to construct connective infrastructure projects with ASEAN so long as Myanmar remains unstable. The only two things India can do to stabilize its neighbor are: solidly committing to a full-fledged joint military operation against all rebel groups there (close to impossible); or stay out of Myanmar’s domestic peripheral affairs (no matter how tempting or provocative the bait) and give full diplomatic and military material support to its government. Until Myanmar can be stabilized and its civil war be resolutely brought to a close, India’s physical influence in ASEAN will always remain tenuous without the international connective infrastructure to tether it to the region.

This benchmark is one which is still a long time away from being reached, if ever, and India’s anti-terror strike may have conversely destabilized its neighbor even more. It will be discussed more in the forthcoming scenario forecasts, but for all intents and purposes, while India has its reasons for intervening in Myanmar, it may have upset the fragile truce underlying the tense balance in the country. Even if India is able to fully integrate the Northeastern states into its full-spectrum national economy, using Bangladesh as a bridgehead in doing so, it will be unable to construct connective infrastructure projects with ASEAN so long as Myanmar remains unstable. The only two things India can do to stabilize its neighbor are: solidly committing to a full-fledged joint military operation against all rebel groups there (close to impossible); or stay out of Myanmar’s domestic peripheral affairs (no matter how tempting or provocative the bait) and give full diplomatic and military material support to its government. Until Myanmar can be stabilized and its civil war be resolutely brought to a close, India’s physical influence in ASEAN will always remain tenuous without the international connective infrastructure to tether it to the region.

The Northeast Frontier

India’s gateway to ASEAN begins at its Northeastern states, colloquially referred to as the ‘Seven Sisters’. This distant region is a patchwork of different ethnicities, religions, and administrative boundaries, some of which don’t correspond to the most ‘advantageous’ alignment for stability. That is to say, there are overlapping conflicts between certain demographics and their perceived ethnic homelands which leads to an inherently unstable situation that’s ripe for eruption. 57 out of the country’s 65 officially designated terrorist groups are active in the Northeast, and they’ve been wreaking havoc on and off since India’s independence in 1947. The core of the terrorists’ complaints is that their respective ethnic regions were unfairly incorporated into India and should instead be granted independence. Other than the obvious security reasons for why New Delhi fights against the ethnic terrorists, another reason is more metaphysical, and it has to do with the entire legitimacy of India’s current boundaries.

Separatists in the Northeastern states believe that their respective areas were forced to sign instruments of accession that brought them into the Republic of India, and that the actual agreements are thereby voided due to their imposed nature. This dangerous line of thinking questions the very underpinning of many of India’s current territories, and if one separatist movement succeeds in its goal, then it could set off a domino reaction within its region, and perhaps even the country. This reasoning explains why India resorted to the extreme measure of using its air force against the Mizo National Front in 1966 after they overran Aizawl, which was the only time that India ever bombed its own territory. That drastic action speaks to the seriousness with which New Delhi takes separatist threats, so it should ultimately come as no surprise then that it would launch a special forces operation in Myanmar after suffering its worst ambush in two decades, especially against as strategically dangerous of an adversary as UNLFW.

Separatists in the Northeastern states believe that their respective areas were forced to sign instruments of accession that brought them into the Republic of India, and that the actual agreements are thereby voided due to their imposed nature. This dangerous line of thinking questions the very underpinning of many of India’s current territories, and if one separatist movement succeeds in its goal, then it could set off a domino reaction within its region, and perhaps even the country. This reasoning explains why India resorted to the extreme measure of using its air force against the Mizo National Front in 1966 after they overran Aizawl, which was the only time that India ever bombed its own territory. That drastic action speaks to the seriousness with which New Delhi takes separatist threats, so it should ultimately come as no surprise then that it would launch a special forces operation in Myanmar after suffering its worst ambush in two decades, especially against as strategically dangerous of an adversary as UNLFW.

Greatest Concerns:

While many ethnic groups inhabit India’s Northeast, four of them in particular are at the greatest risk of generating significant separatist violence:

Assamese/Bodo

The state of Assam used to be administratively a lot larger than its present-day form, having previously incorporated all of the Seven Sisters besides Manipur and Tripura. Ethno-political considerations led to New Delhi subdividing the state until it received its present form, largely as a means of placating the various minorities that agitated for independence. Some Assamese, however, have forcefully rejected the unilateral shrinking of their territorial boundaries and want independence in order to halt, and possibly even reverse, this process. The United Liberation Front of Assam is the most notorious of the Assamese terrorist organizations fighting for this goal, and it’s also one of UNLFW’s constituent members.

Located within the current borders of Assam is the Bodo ethnic minority, which has been fighting a vicious separatist war against both the local and national authorities since the 1980s. Some of its fighters want autonomy within Assam, some want a separate state within India, and still others aim for outright independence. Bodo terrorists were responsible for the late-December violence that killed over 75 people and caused tens of thousands to flee from their homes, and the author investigated this in detail in an earlier article written at that time. One of the forecasts made in the piece was that the various separatist forces active in Northeast India could temporarily unite in order to pursue their shared goal of secessionism, after which they could fight amongst themselves over the territorial details.

That’s precisely what’s happened with the creation of the UNFLW, since Assamese separatists have linked up with their Bodo counterparts (the National Democratic Front of Bodoland-Songbijit, which was responsible for December’s chaos) to wage a common war. On the surface, these two groups should be at eat other’s throats, since the Bodo want to secede from Assam while Assam wants to control the Bodo, but they’ve been able to put their bloodthirsty feud aside for the sake of joining forces in their shared fight against New Delhi. This testifies to the ideological fervor of their separatist beliefs, since they’re able to move past their on-the-ground ethnic and territorial conflicts in the name of achieving their common goal of independence. It also shows that their respective leadership recognizes the need to unite their forces against the shared ‘enemy’ of India instead of whittling them away in fighting against one another.

Naga

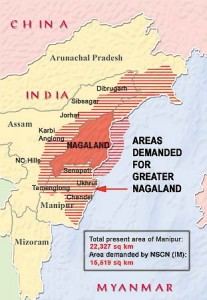

The next main separatist force in Northeastern India is the Naga. Terrorist groups such as the NSCN-K, one of the founders of the UNFLW, want to expand the borders of their current state to include all of their ethnic kin in the surrounding areas, including Myanmar, in a project that they term “Nagalim” or “Greater Nagaland”. Their predecessors were the first group in India’s Northeast to fight for independence in 1947, and the issue has thus formed one of the mainstays of regional destabilization. Some Nagas advocate a ‘soft secessionism’ whereby India is pressured into redrawing its internal boundaries in order to accommodate their designs on neighboring states, but New Delhi is absolutely opposed to this since it would lead to uncertainty, fear, and panic in the minority non-Naga ethnic groups and states affected. It could also create a perilous precedent for other ethnic groups’ demands, thus ushering in a never-ending cycle of administrative revisions that would ultimately lead to violence and actual secessionism (which is the NSCN-K’s end goal).

The next main separatist force in Northeastern India is the Naga. Terrorist groups such as the NSCN-K, one of the founders of the UNFLW, want to expand the borders of their current state to include all of their ethnic kin in the surrounding areas, including Myanmar, in a project that they term “Nagalim” or “Greater Nagaland”. Their predecessors were the first group in India’s Northeast to fight for independence in 1947, and the issue has thus formed one of the mainstays of regional destabilization. Some Nagas advocate a ‘soft secessionism’ whereby India is pressured into redrawing its internal boundaries in order to accommodate their designs on neighboring states, but New Delhi is absolutely opposed to this since it would lead to uncertainty, fear, and panic in the minority non-Naga ethnic groups and states affected. It could also create a perilous precedent for other ethnic groups’ demands, thus ushering in a never-ending cycle of administrative revisions that would ultimately lead to violence and actual secessionism (which is the NSCN-K’s end goal).

Bengali

While no significant secessionist or irredentist groups exist for the Bengali minority in Northeast India, it doesn’t mean that they can’t quickly arise. As the author previous wrote about when discussing Bodo terrorism, there’s a strong concern among native ethnic groups in the region about Bengali migration, both legal and illegal. In some cases, the locals feel threatened by their large influx, and this at times takes on religious overtones of Islam versus Christianity (the latter of which many native people converted to during British rule). In the event that there’s a violent backlash against settled Bengalis in Northeastern India, they could potentially resort to social mobilization in lobbying Bangladesh for protection. Not only that, but some of them might even partake in terrorist action in order to push for unification with their home country. Additionally, if Indian Bengalis somehow form their own ethnic identity separate from actual Bengalis (such as Myanmar’s Rohingya have done), then the possibility is opened that they could seek autonomy or independence along the “Kosovo” model, further complicating the ethno-political mess in Northeast India.

However, these separatist scenarios are currently negligible due to Modi’s breakthrough visit to Bangladesh. By ingratiating himself with its leadership and resolving the territorial disputes between both countries, he’s all but guaranteed that Bangladesh would never support any of its ethnic affiliates in whatever secessionist schemes they might one day be hatching. But, if something unexpected were to occur that leads to a severe straining in bilateral relations, perhaps even a freeze or complete break, then it certainly remains within the realm of possibility that such measures could be contemplated by Dhaka. Still, it doesn’t appear like such a scenario would ever occur anytime soon, if at all, since Modi’s trip symbolically paved the way for a new era of mutual ties, and India acknowledges just how much it needs Bangladesh’s support in stabilizing the Northeast and opening the gates to ASEAN. This in turn makes it much more pliable in protecting the rights and safety of the Bengali minority in the Northeast (whether legal or illegal), and accordingly mitigates the risk of any international crisis breaking out with Bangladesh. Nonetheless, rampant and unrestricted Bengali migration into Northeast India could lead to spiraling tensions with the native locals (especially if New Delhi is seen as being biased towards them or turning a blind eye to the issue), which in turn could strengthen separatist sentiment and lead to the same cycle of violence that India is keen to avoid.

The ISIL Model In ASEAN

Having taken account of the three primary terrorist interests within UNFLW, it’s now time to explain how the group closely mirrors ISIL in its tactics and strategy:

Both terrorist groups unify their members under an umbrella ideology, with ISIL opting for a perversion of Islam while UNFLW uses left-wing separatism. Their ideologies aren’t without contradictions, of course, since ISIL fights against other extreme Islamic groups (such as Al Qaeda and the Taliban) and the UNFLW separatists (specifically the Assamese and Bodo) will inevitably clash with one another over their overlapping territorial disputes if they ever succeed in pushing New Delhi out of the Northeast.

Border And Governance Exploitation:

UNFLW exploits the weakness of the Indian-Myanmar border and nests itself in areas beyond the central control of Naypyidaw, mirroring what ISIL has done along the Syrian-Iraqi border in respect to both of those governments. Of course, the current situation in the Mideast is much more chaotic than that in Southeast Asia (by a long shot!), but the dangerous template of exploiting geopolitical lines and ungovernable territory to one’s advantage is clearly being followed by UNFLW.

Hybrid Tactics:

ISIL expertly juggles unconventional and conventional warfare, mixing terrorist and insurgent attacks together with its utilization of conventional armaments and deployment tactics. UNFLW has yet to seize military hardware or bases from India or Myanmar, but it may realistically have access to standard military equipment and training regimens via the rebel pseudo-armies that it’s allied with in Northern Myanmar. Only time and combat experience against them can reveal whether they’re capable of waging a conventional war, but it must be assumed that they harbor at least some of these capabilities.

Wide Base Potential, Strategically Positioned Supporters:

UNFLW could potentially mobilize a base of over 22 million supporters, which is the estimated total number of Assamese, Bodo, and Naga in Northeast India. Not all of them would realistically support the separatist umbrella, but considering the large numbers at play here, and especially the fact that secessionist tensions have been ripe in this region for decades already, it’s likely that a sizeable proportion of the population would at least be sympathetic to their cause. In an area as geographically compact as Northeast India is, even a few thousand civilian supporters could make a noticeable impact in the group’s intelligence, infiltration, and insurgent capabilities.

ISIL, on the other hand, has a much wider intended support base (over one billion), but as with UNFLW, it’s impossible for them to ever reach it. Instead, as has been seen through their battlefield operations, scattered bands of supporters could play a pivotal role in the success of their offensives (as they did in Mosul, for example). The key is simply that their supporters are in the right place at the right time, and they’ve already demonstrated that they can pull this off. Thus, it’s not outside the ability of the UNFLW to do something similar if it ever intends to launch a hybrid offensive on Indian or perhaps even Myanmar territory.

Territorial Relationship:

ISIL and UNFLW have intimate territorial relationships that differentiate them from all other terrorist groups, in that they’ve demonstrated an ability to actually hold territory. ISIL does so with a lot more success (e.g. Mosul, Raqqa) than UNFLW, which has no known villages or towns under its control, but the fact remains that they do administer their own pseudo-autonomous area in Myanmar, and NSCN-K is a signatory party to the country’s tenuous nationwide truce. Furthermore, both terrorist groups strive for state-like legitimacy over their respective conquests, and UNFLW aims to establish a government-in-exile by November of this year. There’s no grounds to expect that they’ll be taken seriously at this point, but the significance in this step would be to solidify the unity between the UNFLW’s diverse members and underline their shared goal of separatism (by terroristic means). Just as ISIL has dreams of further territorial conquests past its current holdings, so too does UNFLW, and it’s expected that both terrorist groups will continue playing the ‘territorial card’ to their advantage for marketing and recruitment purposes (with UNFLW perhaps entering the social media sphere in the near future to assist with this).

Pingback: A “Secular ISIL” Rises In Southeast Asia (II) | Oriental Review

Pingback: A “Secular ISIL” Rises In Southeast Asia By Andrew KORYBKO - Progressive Radio Network

Pingback: For Russia, The Path To Laos Runs Through Vietnam | The Vineyard of the Saker

Pingback: What’s Wrong With Turkey ? | YERELCE

Pingback: Laos is a Key Country in Russia's Pivot to Asian Integration – Andrew Kroybko | Timber Exec

Pingback: Laos is a Key Country in Russia's Pivot to Asian Integration - Business Recorders Russia News

Pingback: The Russian-Chinese-Indian Strategic Convergence In Myanmar: PART II | The Vineyard of the Saker

Pingback: Myanmar: Drawn-Out Peace Or Battle Lines Drawn? (I) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Myanmar: Drawn-Out Peace Or Battle Lines Drawn? (II) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Myanmar’s Protracted Civil War: Drawn-Out Peace Or Battle Lines Drawn? | SHOAH

Pingback: Indian Ocean As A Prize Or Crisis Of Multipolarity? (III) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Indian Ocean As A Prize Or Crisis Of Multipolarity? (III) | Alternate NEWS Blog

Pingback: 2016 Trends and Geopolitical Forecast: Mega Analysis of Europe, Eurasia and the Middle East | Counter Information

Pingback: Mega analysis: 2016 Trends Forecast by Andrew Korybko - GPOLIT

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar (IV) | Oriental Review

Pingback: Asian NATO-like project to be stopped (II) – OrientalReview.org