China secured one of the most important deals of this century so far, and it’s the $2.65 billion that it paid for the Tenke mine in the southeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, or hereafter referred to simply as the Congo) at the end of May. The Financial Times has an informative write-up on the significance of this breakthrough agreement, which they forecast will make China the world leader in electric battery technology in the future due to its control over 62% of the global cobalt market, the demand for which they expect to spike by two-thirds in the next ten years. Strategically speaking, this puts China at the forefront of the worldwide movement towards electric vehicles, thus giving the multipolar leader yet another notch in its belt over the unipolar world in attaining influential control over the future of personal, commercial, and military transport systems.

The unmistakable problem though, is that China receives 93% (or according to Bloomberg, 99%) of its cobalt from the Congo, meaning that its future outlook as a global leader in the electric battery field is completely dependent on this fragile country’s stability, which the US immediately began undermining ever since its 1960 independence. The scene of “Africa’s World War” in the 1990s and the related graveyard of an estimated 5 million people as a result, the Congo is once more being pushed dangerously close to the precipice of disaster because of the international intrigue that surrounds it. It’s not just wild speculation either – the US and its affiliated unipolar information outlets have been busy preconditioning the world to expect a disaster in the DRC if incumbent President Kabila doesn’t step down at the end of his second and constitutionally last term in office by the end of the year, and instead indefinitely delays the upcoming vote and/or changes the constitution to run once more.

There’s no question that the Congo is in the US’ New Cold War crosshairs and that the country should brace for what might very well turn out to be another prolonged period of catastrophic conflict, but what’s happening in this Central African state right now and what might soon transpire there need to be placed in the appropriate global context. Accordingly, the research thus begins by explaining the centrality of the Congo to China’s grand African strategy. After the full significance of the country has been established and the reader is more aware of the reasons why the US wants to throw it into chaos, the work then proceeds to describing the indirect warfare that has been simmering around the Congo over the past year. Finally, considering that the aforementioned indirect plans had miserably failed, the last part of the article speaks to the ways in which Washington is trying to directly strike at Kinshasa and manufacture several Hybrid War scenarios in the geostrategic Heartland of Africa.

Beijing’s Big Ambitions In Africa

Congo is back in the global headlines not because of its expected leadership transition (or lack thereof), but because of its significance to China in the context of the New Cold War. Most people are aware that China is pursing the One Belt One Road vision of constructing “New Silk Roads”, or infrastructure corridors, all across the world, but practically nobody has comprehensively studied how this is expected to relate to Africa. The author undertook such a mission in a previous article for Oriental Review about how “East Africa’s Problems Might Spoil Its Silk Road Dreams”, and most relevantly, it was revealed that China is working hard to construct two transoceanic trade routes linking the continent’s Indian and Atlantic Coasts. While the intent to do so has yet to be officially declared, it’s clear to see that this is what Beijing is in essence doing, even if the two projects are not yet completed.

Northern Transoceanic African Route (NTAR):

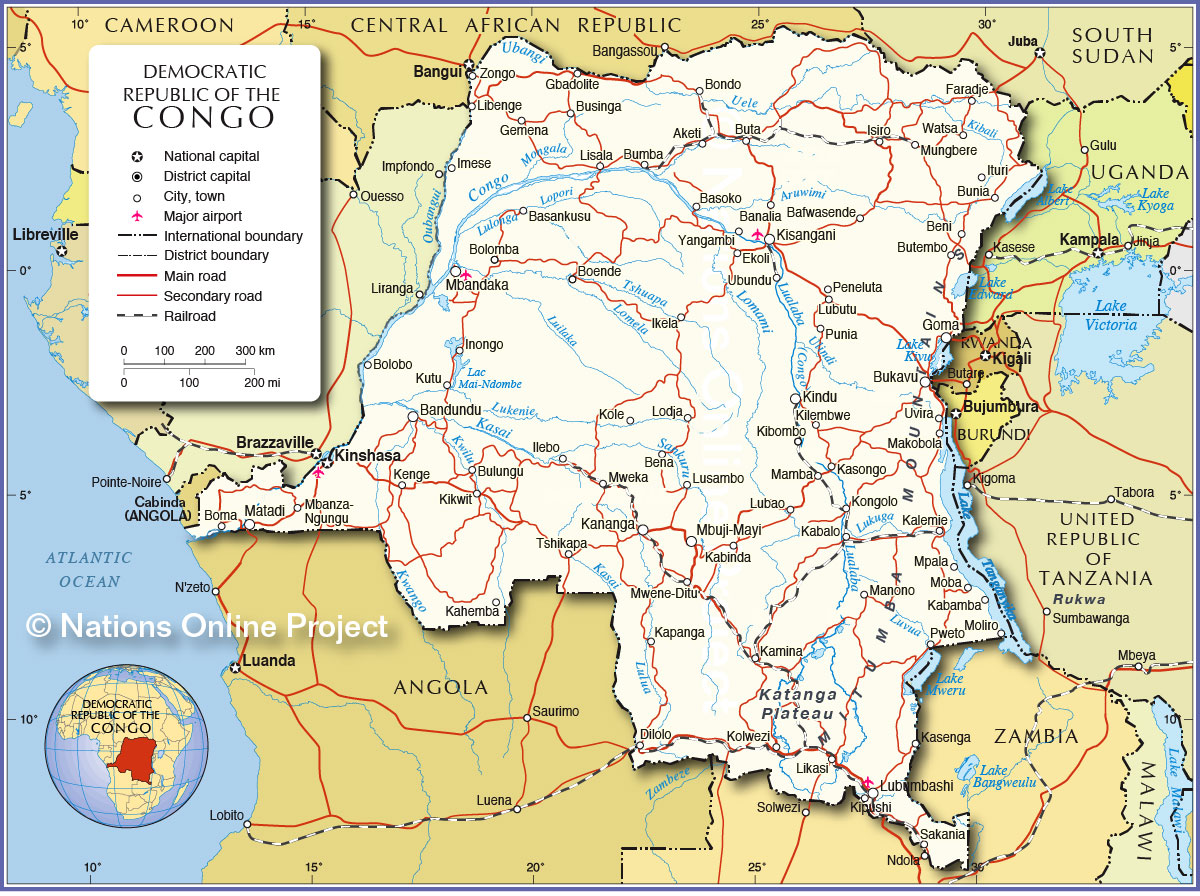

The northern route is expected to be an intermodal one that incorporates railroad and riparian infrastructure, linking Kenya’s Indian Ocean port of Mombasa with its Atlantic counterparts in the DRC’s Matadi and/or the Republic of the Congo’s Pointe-Noire. The Standard Gauge Railroad (SGR) currently has plans to go from Mombasa to the Ugandan capital of Kampala, though it could soon thereafter be extended to the northeastern Congo city of Kisangani on the banks of the Congo River. From there, the world’s deepest river is navigable all the way down to the DRC capital of Kinshasa and its Republic of the Congo twin capital of Brazzaville. Proceeding from Kinshasa, it’s just a short rail ride to the underdeveloped Atlantic port of Matadi, while the rail trip from Brazzaville to Pointe-Noire is a bit longer but ends at a more developed deep-sea port.

Inga 3 Dam:

The northern route has an added significance because of its near proximity to the future Chinese-constructed Inga 3 Dam, which The Guardian estimates will be the largest in the world upon its completion. To cite the British outlet, this megaproject would be able to provide 40% of Africa’s electricity needs because of its potential to generate as much power as twenty nuclear reactors. Although its construction has yet to begin, it could start as early as the end of this year, and it’s expected that this colossal feat of engineering could one day allow China and its Congolese host to wield multipolar influence across most of Atlantic and Central Africa. It should come as no surprise then that the article also reports that this project is coming under heavy Western NGO opposition presumably due to its possible environmental impact and the fact that upwards of 35,000 people might have to be relocated because of it. If the US doesn’t succeed in forcing Kabila to step down at the end of his term and thus allow a pro-Western replacement to exert unipolar proxy control over this regionally impactful project, then the fallback plan is to precondition the masses for accepting that “disgruntled villagers and/or rebels” might attack it in the midst of a forthcoming Hybrid War scenario.

Southern Transoceanic African Route (STAR):

Concerning the southern route, the Chinese-built TAZARA railroad from the 1970s already links the Tanzanian coast near the country’s largest city of Dar es Salaam to the copper-rich regions of central Zambia. From here, other rail infrastructure had been independently built through the mineral-rich southeastern Congolese region of Katanga, nowadays divided into several smaller states but still retaining its strong sense of a distinct unified identity. The Katangan railroads used to be linked to Angola’s Benguela railway, but had fallen into disrepair over the years and have yet to be put back into service in connecting to its western neighbor. Also, the Benguela railroad had been offline for decades ever since Angola’s bloody civil war broke out in the 1970s, and it was only through the recent pivotal help of the Chinese that it was modernized and recommissioned. It won’t just be the Katangan railways that connect to Benguela and thenceforth to the Atlantic, though, since China also envisions extending TAZARA from central Zambia to the Angolan-Congolese junction via the North West Railroad project.

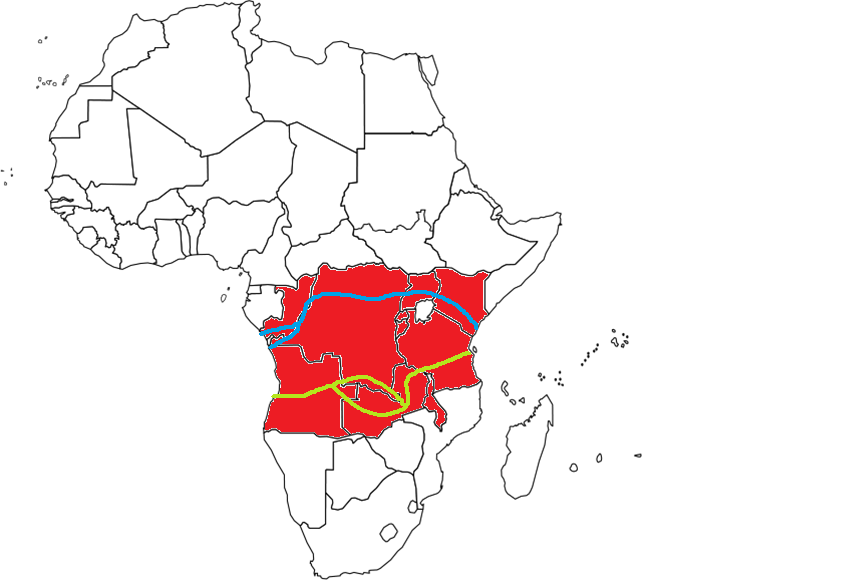

The author created the below map to make it easier for the reader to visualize these grand ambitions:

Red: countries whose stability directly or indirectly affects the viability of China’s projects

Blue: the Northern Transoceanic African Route

Green: the Southern Transoceanic African Route

As can clearly be seen, 7 separate African countries are directly connected to these two projects, with 3 others being so closely linked in terms of the regional geostrategic paradigm (Rwanda, Burundi, and Malawi) that their stability directly impacts on these routes’ viability. It’s these 3 states and the Republic of the Congo that form the basis of the next section in describing how the US tried to pursue indirect warfare against the Transoceanic African Routes before resorting to the gambit of directly destabilizing the Congo.

Indirect Warfare

The author’s proposal about “The Law Of Hybrid War” teaches that “the grand objective behind every Hybrid War is to disrupt multipolar transnational connective projects through externally provoked identity conflicts (ethnic, religious, regional, political, etc.) within a targeted transit state”, but sometimes, the US is willing to accept the existence of a said project so long as it can influence and/or control it. The Northern and Southern Transoceanic African Routes, while expectedly being a bonanza for Beijing, could also be used by India and other countries that choose to ‘piggyback’ off of them in order to deepen their influence over this part of the world as well. With this in mind, the US actually sees a large degree of strategic benefit in having China foot the bill for these ambitious projects in order to have its rival pay for the same transport networks that the US and its allies will also inevitably use to a certain extent.

Destabilizing With Discretion:

Be that as it may, however, the US is also cognizant that China could end up being the ultimate beneficiary by inversely coming to control the same trading routes that America’s unipolar allies might eventually become dependent on. Therefore, the US became interested in indirectly ‘putting the brakes’ on China’s plans, or in other words, disrupting these two projects to the extent that they are only partially actualized or utilized (and thus accessible to Washington’s allies as well), but not fully completed to the transcontinental point of enabling China to gain commanding influence over the African Heartland and thus be in a position to exert multipolarity throughout the rest of the continent. This is why the US prioritized the destabilization of ‘peripheral’ points along these two lines such as Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi, and the Republic of the Congo instead of disrupting them directly in their Kenyan and Tanzanian coastal origins (though that’s of course also a possibility in the future if the US sees the need). Furthermore, these two latter countries are also very close to US-ally India, which is Kenya’s second-largest import partner and Tanzania’s top import and export one, and it would disrupt New Delhi’s “Cotton Route” counterstrategy to the New Silk Road if they descended into turmoil (though recent events in Kenya suggest that the US might be willing to risk that).

Burundi, Rwanda, and Malawi:

Anyhow, taking a look at the four ‘peripheral’ countries mentioned in the above paragraph, it seems as though their recent destabilizations are all related to the US’ objective of stopping the expansion of the two Transoceanic African Routes. The Western-concocted unrest in Burundi that the author wrote about in his earlier Oriental Review article titled “EU To Burundi: Regime Change Trumps Anti-Terror Help” was partially conditioned to spark a regional conflagration that would inevitably suck in Rwanda and lead to “Weapons Of Mass Migration” spilling across the region into Uganda and Tanzania, to say nothing of the extent to which they’d aggravate the Congo’s already existing low-intensity conflicts in Ituri and North & South Kivu provinces. The practical effect of this Great Lakes-wide destabilization would be to contain the Transoceanic African Routes in the East African Community and prevent their linkage to the Atlantic. Malawi figures into the equation by being the target of a planned coup organized by the US and Germany, and which was only averted at the very last minute after a couple high-profile and predictably Western-condemned arrests. The plan was to use the coup government as an instrument for fomenting regional tension and instigating a civil war between the northern and southern parts of the country, which would also have unleashed “Weapons of Mass Migration” into Tanzania and possibly combined with Burundi’s in making TAZARA unviable.

The Republic of the Congo:

In relation to the Republic of the Congo, the US wanted to disrupt the second access/terminal point of the Northern Transoceanic African Route by disabling the Congo-Ocean Railway between Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire. Analyst Gearoid O’Colmain has done an excellent job raising awareness about the incipient Color Revolution that the US tried to unsuccessfully foster, and it’s recommended that the reader refer to his writing on the matter for additional details, but in short, the US and its French neo-colonial bulldog wanted to use the event to trigger a return to the country’s 1990s-era civil war. This was eventually put down by the government, but before it was, the unipolar-aligned media spent months presenting the Republic of the Congo as Africa’s latest conflict hotspot. The strategic objective wasn’t just to replace President Nguesso with a pliant Western puppet, but to kick Chinese influence out of the country and render it impossible for Beijing to use its territory as a complementary alternative to the Kinshasa-Matadi railway in actualizing the Northern Transoceanic African Route. If successful, then it would have made China completely dependent on the Color Revolution-prone DRC capital of Kinshasa and thus severely curtailed its strategic flexibility in managing this portion of the transcontinental project that it de-facto spearheaded.

Assessing The Plots:

Reviewing events in the examined area over the past year, it convincingly looks like the US tried but failed to succeed in indirectly sabotaging the two Transoceanic African Routes through its conflict instigation in Burundi, Malawi, and the Republic of the Congo. The residents of Bujumbura were resilient in opposing the US’ temptations to return their country to the throes of genocidal civil war, thus diminishing the prospects of a Rwanda conventional or covert invasion and the explosion of a new immigrant crisis all across the African Great Lakes Region. Pertaining to Malawi, the authorities caught wind of the coup plot and exposed it before it could enter into action, which had the effect of counteracting the entire destabilization and causing its architects to go back to the drawing board. Finally, in regards to the Republic of the Congo, the government eventually managed to crush the Color Revolution movement and prevent the return of Hybrid War in their country, which resulted in the Northern Transoceanic African Route’s second terminus/access point remaining open and consequently giving China a much-needed alternative to Kinshasa in case the need ever arose.

The Third Congo Crisis

In light of the US’ failures to indirectly “contain” the Transoceanic African Routes, it now seems as though Washington has decided to step its aggression up and proceed to destabilizing Africa’s geopolitical Heartland, the Congo. Other than sabotaging Beijing’s two transcontinental projects, the large-scale renewal of conflict in the Congo could easily jeopardize China’s cobalt trade with the country and subsequently offset Beijing’s plans for becoming the world’s premier leader in electric battery technology and reaping all of the resultant strategic advantages. The trigger for sparking another round of violence in the Central African state is President Kabila’s presumable desire to continue ruling over his country after his mandate constitutionally expires at the end of the year. In a sense, this is very similar to what happened with Burundi’s President Nkurunziza, thus making Congo a structurally larger example of the Burundian scenario and raising the educated question about whether or not the East African country’s destabilization was a test run for what was already being planned for the Congo.

Historically speaking, this Central African state has already been the scene of two globally reported-on crises, the First Congo Crisis from 1960-1965 and the Second Congo Crisis from 1996-2003 (sometimes counted as two separate events). Not only were they crises, but they were actually a hybrid combination of civil and international wars, too, making them the tactical military epitome of Hybrid War. With Congo on the verge of yet another crisis that could foreseeably descend into a new civil and international war, it’s appropriate to speak about the Third Congo Crisis that the US is working to engineer in order to “contain China” through “controlled chaos”. As such strategies have a knack for doing, it’s very likely that the subsequent three “controlled chaos” scenarios that will be described below could evolve in unpredictable directions and unleash even more destabilization than can be predicted at this time, but it’s still forecast that they’ll generally adhere to the phased progression outlined below if the US does in fact give the greenlight for the operation to commence.

Color Revolution In Kinshasa:

Proceeding from the assumption that the US will in fact victimize the Congo with Hybrid War if Kabila tries to delay the upcoming elections or amend the constitution, the Third Congo Crisis would ‘naturally’ begin with a Color Revolution, such as through the urban provocations that have been taking place in Kinshasa and Goma as of late. The objective is to install a pro-Western or Western-friendly leader into power that would thus allow the US to indirectly control China’s cobalt trade and exercise influence over the Transoceanic African Route. The man envisioned to fulfill this role on behalf of Washington is former Katanga governor and millionaire businessman Moise Katumbi, the public face of the Color Revolution opposition. He was charged last month with hiring mercenaries (including ‘former’ US soldiers, according to the affidavit) and has since fled to South Africa and most recently to London for “medical treatment”, where he will likely try to gin up even more foreign backing for his candidacy under the auspices that he’s a “democratic leader” being “politically harassed” by a “dictatorship” – the perfect buzzwords for guaranteeing strong Western support and producing a unipolar media-driven global information campaign about his political ambitions. While abroad, it can be safely assumed that he will be in close contact with Western intelligence agencies and the secret services of their allied African “partners” in managing the Color Revolution and formulating the most efficient way to take down President Kabila’s government.

Cutting Katanga Out Of The Congo:

If the Congolese Color Revolution is eventually deemed to be a failure just like the Burundian one was, then it’s very possible that “Plan B” is to revive Katanga’s historic secessionist claims and have Katumbi return to the region to lead the insurgency alongside his army of foreign mercenaries. This is essentially a copy-and-paste template of what started the First Congo Crisis in the weeks immediately after the country’s 1960 independence, so the reader is forgiven if they’re sensing déjà vu while reading this. What differentiates this predicted future step from the one that preceded it nearly 60 years ago is that a major non-Western country, China, now has very important mining investments in the four southeastern provinces that used to comprise this formerly unified area. This means that an independent Katanga wouldn’t necessarily impede China’s cobalt trade or either of the two Southern Transoceanic African Routes unless Katumbi purposely took steps to obstruct them, but it’s a reliable bet that the period of war that would precede this possible eventuality could seriously disrupt all trade to and from the province.

From the Western perspective, although China is heavily involved in Katanga, an outbreak of large-scale violence there similar to what happened in Libya in 2011 could lead to a mass evacuation of China’s citizens and the abandonment of its capital investments, provided of course that China doesn’t try to defend its interests this time around. Should Beijing unprecedentedly attempt this in accordance with its newly promulgated African policy, then it could likely take the form of “Leading From Behind” in assisting the Congolese Armed Forces, and possibly their regional allies as well if the conflict becomes formally internationalized by that point, through material, intelligence, and advisory support short of direct Chinese military engagement with the separatists. China should be keenly aware that if Katumbi succeeds in a forthcoming secessionist campaign to establish an “independent” Katanga, then Chinese companies would eventually be booted out and replaced with their Western counterparts on whatever pretexts could be manufactured, be it that Beijing supported Katumbi’s “enemies” in Kinshasa during the war or simply via a state expropriation scheme. A revival of the Katanga separatist campaign would be as regionally destabilizing to this part of Africa as the territorially revisionist aspirations of Daesh have been to the Mideast, potentially leading to a multisided military conflict and setting the stage for a “Second African World War”.

Great Lakes, Greater Conflicts:

Following the start of a second Katangan secessionist conflict or possibly even independent thereof, the eastern part of the Congo might erupt into Hybrid War violence following Katumbi’s failed Color Revolution in Kinshasa. This part of the country has historically been the most unstable and is responsible for the Second Congo Crisis (essentially a series of back-to-back civil and international wars), and the unresolved situations in Ituri and North & South Kivu Provinces are perpetually on edge of exploding once more into all-out war due to the presence of dozens of Rwandan and Uganda militias, both pro-government and rebel ones, including the Islamist “Allied Democratic Forces”. Furthermore, the $24 trillion of untapped minerals in the eastern Great Lakes Region of the country have been taken hostage by these groups and corrupt government elements and subsequently branded as “conflict minerals”, thus making them ethically undesirable to many despite their irreplaceable role in manufacturing modern-day cell phone technology.

For these reasons, the eastern Congo is one of the most geostrategic regions of the entire world, and its stability directly impacts on the global mineral and technology markets. Nowadays a cold peace is in place and foreign customers either procure their resources directly from some of the rebel group’s Ugandan and Rwandan state sponsors or the Congolese government, or informally work through rebel intermediaries and corrupt officials, thus facilitating access to the resources and allowing for their sale on the world market. However, if the region slid back into violence, not only would that disrupt the existing trade flows, but it could also create a situation where one actor gains control over all of the mineral wealth, which would thereby allow it to become a superpower in this globally important industry. The existing de-facto division of the region between Ugandan, Rwandan, and Congolese government-affiliated and ‘rogue’ non-state actors has created a certain balance of economic-military forces and prevented this from hitherto arising, but if Kinshasa for example were able to regain full sovereignty over its eastern territories, then the Congo could quickly rise as a continental power if it properly leveraged its mineral position and managed the resultant benefits accordingly.

Due to the magnitude of what’s at stake in geostrategic and economic terms, a renewal of conflict in the African Great Lakes Region would easily have the potential to become a global crisis, especially if sparked in connection to the regime change threat that forebodingly hangs over the Congo. The US’ supreme interests in seeing this happen would be to either disrupt the existing mineral flow out of the Congo and thereby weaken China’s industrial capacity in this sphere, or to begin the process of geostrategically reorganizing the mineral-rich area and backing a regional hegemonic force to consolidate all of its natural wealth under a single, integrated command. While the US stands to experience varying degrees of ‘collateral damage’ as a result of the Congo’s third possible collapse since independence, it might cynically wager that it has even more to gain by going for this gambit and manufacturing a major war in pursuit of its zero-sum self-interests in relation to China.

Concluding Thoughts

China is pulling off big moves in the Congo, be it with the Northern Transoceanic African Route megaproject and the Katanga portion of its southern counterpart, the Inga 3 Dam, or the industry-shaking purchase of the Tenke cobalt mine. These strategic initiatives complement one another and make the Congo among one of China’s top international partners, whether in Africa or anywhere else in the world. The three aforementioned projects in the continental Heartland provide China with a strong foundation for projecting multipolar influence throughout the rest of Africa and gradually reshaping the geostrategic paradigm, transforming one of the weakest semi-failed states in a generation into a stable beacon of prosperity. Nevertheless, the Congo still has a long way to go before it comes anywhere close to that vision, and it’s precisely during this developmental period that it’s most susceptible to the US’ Hybrid War schemes against it.

The leadership transition that’s planned at the end of the year might be indefinitely delayed or avoided if incumbent President Kabila succeeds in amending the constitution to run for a third term. The US is already exploiting the situation to prepare for a Color Revolution if that happens, but if its first phase of regime change pressure fails, then it’s very probable that it’ll proceed to escalating the situation to Hybrid War proportions. Should that transpire, then it can be expected that former Katanga governor and present opposition leader Moise Katumbi might rekindle his home region’s historic separatist campaign in recreating the conditions that led to the First Congo Crisis in the 1960s. In parallel with, as a result of, or independent of that, the eastern Congolese provinces of Ituri and North & South Kivu might re-erupt in an orgy of violence that resembles the early stages of the Second Congo Crisis of the 1990s.

The worst-case scenario would be if both conflicts merge into a unified one, which would thus make the chaos of the Third Congo Crisis dwarf that of its two predecessors. Needless to say, such a development would inevitably lead to the US-provoked civil war becoming internationalized, ushering in “Africa’s Second World War” and totally upending China’s continental strategy. Beijing’s Northern and Southern Transoceanic African Routes would be dead in their tracks, and Kinshasa would have a lot more urgent things to worry about then constructing the Inga 3 Dam. Moreover, whether it’s mired in war or reunited as an independent pro-Western vassal, the former Katanga Province would cease to be a reliable cobalt supplier to China, and Beijing would likely end up losing billions of dollars in investments if its mines became unusable or ended up being expropriated. An untold amount of human suffering will probably accompany any large-scale outbreak of violence in the Congo, but from the American grand strategic perspective, it might all be worth it so long as it results in “containing” China and keeping Beijing out of the African Heartland.

Andrew Korybko is the American political commentator currently residing in Moscow. Thew views expressed are his own. He is the author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland

Hybrid Wars 5. Breaking the Balkans

Hybrid Wars 6. Trick To Containing China

Hybrid Wars 7. How The US Could Manufacture A Mess In Myanmar

Pingback: Hybrid Wars 8. China, Cobalt, And The US’...