The standardization of the Dutch language

The history of the standardization of Dutch and of the political partition of the Netherlands (the Low Countries) gives significant insights into the role of language in the modern Netherlands (called as well as Holland) and Belgium. The fact that the standardization process finally resulted in the inclusion of both northern and southern linguistic features in the standard language of North Netherlands made the eventual adoption of the northern Dutch standard in Belgium more feasible. Historically, the political partition of the Netherlands at the same time secured the future of the Dutch language in the Netherlands (today composed by twelve provinces of whom Holland gives two) while on other hand gravely endangered the linguistic position of the Flemish dialect and its speakers in the south.

The renaissance era of and the interest in the national language is the background of the future linguistic nationalism and, therefore, the development of standardized Dutch language has to be understood. The purification of the Dutch language of, for example, French influences, was important – German loan words were in general preferred to French ones. The influence of French was not only due to the bilingual situation in what nowadays is Belgium but as well as due to the position of the French in Europe as the lingua franca especially during the Dutch Golden Age in the 17th century when the Dutch-speaking people were active and powerful in international trade and other businesses. That was for that reason in addition to the direct linguistic contacts via different channels how the French linguistic influences found their way to the Dutch language. However, at the same time, rejecting these influences was a way to prove that the Dutch are also an important, independent state and nation. The Dutch people, culture, and language intended to be more related to the Germanic than the French tradition of Europe. Today, the Dutch of Belgium is less tolerant of French influences on the language than the Dutch spoken in Holland. This can be seen in spelling and in some terms, which in the area of the Netherlands are rather borrowed from the English while the Belgians are keen on developing their own “indigenous” terms.

In the late 19th century, there was a big discussion over the standardization of literal Flemish based either on the Dutch of Holland or the Flemish tradition. The differences between the dialects are quite big, most of all in pronunciation. In 1914, it was finally decided that the literal Netherlandic of Flanders is going to be based on the cultivated Netherlandic of Holland. This standard language is known as algemeen beschaafd Nederlands (common “higher” Dutch, abbreviation the ABN). Therefore, only at the beginning of the 20th century, it was acknowledged that the languages in Belgian Flanders and the neighboring Holland are, basically, the same or very similar from the linguistic viewpoint (from the sociolinguistic viewpoint they can be separate languages).

The earliest leaders of the Flemish Movement spoke their dialects, but slowly it became more and more popular in the nationalist Flemish Movement to start speaking the ABN. That was promoted, for example, through some Flemish cultural foundations. A linguistic practice of diglossia, the use of two languages or dialects of the same, is common in Flanders: the use of local dialect and, at least to some extent, the use of the ABN.

The earliest leaders of the Flemish Movement spoke their dialects, but slowly it became more and more popular in the nationalist Flemish Movement to start speaking the ABN. That was promoted, for example, through some Flemish cultural foundations. A linguistic practice of diglossia, the use of two languages or dialects of the same, is common in Flanders: the use of local dialect and, at least to some extent, the use of the ABN.

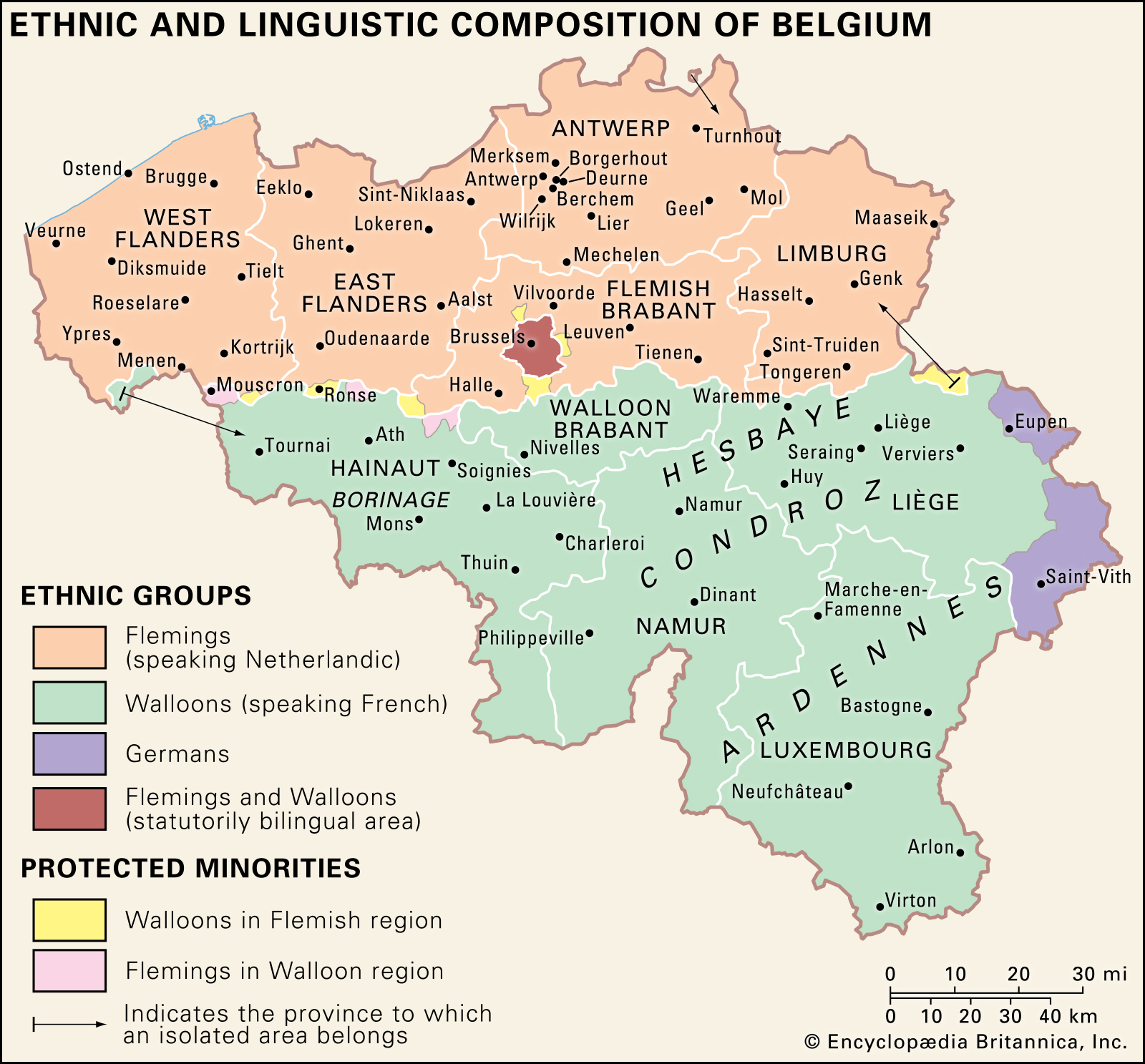

The population and, therefore, the language distribution between the regions have been changing lately in Belgium. The population of Flanders has increased more than three times faster than the Francophone population of Wallonia or Brussels. Brussels and Wallonia, in contrast to Flanders, have negative birth-rate and, therefore, the ethnic-regional demographic situations in Belgium are very different. This has also led Wallonia to be more interested in immigration policies compared to Flanders. The Walloon public has developed persistent feelings of defensiveness, insecurity, and pessimism about the future that has increased its sensitivity in other aspects of language policy. These negative feelings were reinforced, for example, by the economic recession in the 1970s and 1980s. In Flanders, there have been no concerns over the falling birth-rate: one of the central motifs of the Flemish Movement in the 20th century was the idea of volkskracht – the collective strength of the Flemish people. One of the major components of such national policy is demographic vitality (the same policy, for instance, was adopted by Kosovo’s Albanians after WWII or the Palestinians in their struggle against the Zionist Israel). Consequently, the population in Flanders is relatively younger in comparison to Wallonia (the same as Kosovo’s Albanian or Palestinian cases).

The Belgian system was premised for a long time on greater prestige for the French language and its adoption by the middle classes, especially in the Brussels area. This led to Wallonia to maintain its leading position despite the demographic advantages of Flanders followed by the further development of the nationalist Flemish Movement.

The language model in Belgium is dating back to 1830 and up to the beginning of independence, it was not sustainable in the changing conditions of the country. According to the old model from 1830, the three dialects (or separate languages) – the Flemish, the Walloon, and the German – should be used equally for the regional purposes, but the French would be the only language used in wider public communication (as the lingua franca of Belgium). The attempt to raise the status of the Flemish was seen as “unprogressive” or “backward-looking”. With the advance of the democratization process, this model was not of any use anymore and the new model gave the ABN the same position that the standard French had.

Feelings of group superiority and inferiority exist between the Walloon and the Flemish people: for instance, the French-speaking people (at least used to) consider the Flemish just as a set of dialects and not as a real language. Still is the existing refusal of the French-speaking people to learn Dutch what can be understood as a refusal to accept its speakers on equal terms. A French-speaking politician could hold a press conference for the combined media of Belgium solely in French, which would be unthinkable in the Flemish.

The “natural” cultural orientation of the Flemish-speaking people towards Holland was blocked by historical circumstances. Because of such development, for several decades, the model for educated Belgians was the French-speaking population. However, the Flemish Movement challenged this view and, for example, the general strike organized in 1960−1961 distilled the feelings of helplessness and minority status of Walloons: it took place only in Wallonia and resulted in the formation of the first Walloon regional political party (Mouvement Populaire Wallon).

The Flemish and Francophone areas had a very different approach to the language legislation question. The Walloons and the Francophones in Brussels have shown a voluntarist or even laisser faire attitude towards language, while the Flemings have been strong partisans of regulation through public policy, seeing the need to protect one’s territory against linguistic infiltration. There are some dialects in Wallonia, but they are not as distinctive as in the Flanders area. In Wallonia, the dialects are endangered and in Flanders very alive, although disapproved by the elite. The rights of the Flemish minority in Wallonia have been neglected and as a response to that, the Flemings have been working towards a unilingual Flanders. They have tried to decrease the need for a high level of cross-linguistic contact by seeking greater cultural and administrative autonomy.

The factor of bilingual Brussels

Brussels has a special position and status as the only bilingual area in Belgium. It is seen as a mixture, a combination of the less desirable characteristics of both the Flemish and the Walloons. The impact of Dutch among the French-speaking population of Brussels attracted the special attention of the researchers as a very peculiar phenomenon. The influences on the vocabulary occur most likely in the private and social sectors, in lower classes, and pejorative language use. These influences are usually called belgicismes, which also include wallonismes, thus not only the influence of the Flemish language on French but also the special features of the French spoken in Belgium have been researched.

The Brussels area is having the highest economic level of development within Belgium – a situation that is much criticized by both linguistic groups from Flanders and Wallonia. The regional crisis and problems can be seen as well as a reaction of the neglected periphery against a privileged center. Nevertheless, despite the traditional cleavages in Belgium, the Brussels area has always its strong impact on the general situation.

The Brussels area is having the highest economic level of development within Belgium – a situation that is much criticized by both linguistic groups from Flanders and Wallonia. The regional crisis and problems can be seen as well as a reaction of the neglected periphery against a privileged center. Nevertheless, despite the traditional cleavages in Belgium, the Brussels area has always its strong impact on the general situation.

Belgium’s cleavages and politics

Almost all political questions in Belgium have been affected by linguistic and regional questions. In general, there is a consensus on political values and the rules of the political game but in some cases, these differences can also be seen in foreign policy. There is also a tendency that some issues which originally are nonlinguistic get an additional interregional and linguistic dimension. That means in reality an additional dose of hostility and suspicion towards the opposite side when solving the issue.

There are three major cleavages, which tend to split Belgium as a country:

- The first cleavage is the Belgian state structure. It is highly centralized, unlike, for example, in Switzerland with its different cantons for different linguistic areas. This centralization of the power in Brussels means a heavy load on the shoulders of the central Government. There is more at stake in the parliamentary arena, which means that the political game is more intense and generous.

- The second cleavage is the religious one taking into account the division between the Roman Catholics (54%) and the Protestants (3%) with the rising Islamic population (5%). It was an important political issue before the linguistic question became political.

- The linguistic division is the third cleavage dividing Belgium as a country. A phenomenon called the verzuiling in Dutch also tends to divide the country politically. The Verzuiling means cultural segmentation on ideological lines. It is quite institutionalized and formalized in Belgium, and most likely served as a model for the nationalist Flemish Movement. But if something is mixing these separating lines, it is the linguistic issue. For example, the three major Flemish cultural foundations (Willemsfonds, Davidsfonds, and Vermeylenfonds), that all had an important part to play in the development of the Flemish Movement, hung together with both the liberal Roman Catholic line and the socialist subcultures of the French-speaking area. They just concentrated on the mobilization of the Flemish masses from both sides.

Traditionally, there have been three great parties in three ideological families: the Roman Catholic, liberal, and socialist. They are well established and have the support of the organizations on the same ideological tendency. Other parties in Belgium are the socialist party and regional parties. In Flemish regions, these regional parties have had support since 1919, but in other areas only from the 1960s onward. Some parties are offshoots of the major parties or other kinds of secessionist lists and short-lived tendencies on both the Flemish and the Walloon side.

A homogenous one-party Government has been in power only once in 1950−1954. The more usual case has been the coalition of two or three traditional parties and the general consensus is typical of the Belgian political culture. Since 1945, all a bit more severe conflicts in Belgian politics have put strains on the political system on one or more of the fundamental cleavages dividing the country (religion, class, language). The Belgian party-system was built more around religious and class divisions than the linguistic factor. The load for the existing system has, therefore, been extremely heavy and has led to changes in the party-system.

The emphasized importance of linguistic and regional issues has led to the emergence of one bigger regional party from several smaller ones in all Belgium’s regions. As a consequence, such practice changed the organization and activities of the traditional parties and the functioning of the party-system in general.

The Volksunie was founded in 1954 as a union of the smaller Flemish parties. It grew out of the Flemish Roman Catholic right-wing and was first seen as quite radical, but later the Volksunie broke all the relations it had with the more militant groups and developed itself into a moderate party. The Volksunie stresses all the important themes of the Flemish Movement (fixation of the linguistic frontier, territorial limitation, the status of Brussels, bipartite federalism, etc.), but developed center-left economic and social program. The Walloon regional parties have been less stable, continuous, and visible in elections. The regional parties on both sides have profited from the networks of linguistic/cultural and regional organizations, whose goals were the same. All parties have also experienced the emergence of Flemish/Walloon “wing”.

The Volksunie was founded in 1954 as a union of the smaller Flemish parties. It grew out of the Flemish Roman Catholic right-wing and was first seen as quite radical, but later the Volksunie broke all the relations it had with the more militant groups and developed itself into a moderate party. The Volksunie stresses all the important themes of the Flemish Movement (fixation of the linguistic frontier, territorial limitation, the status of Brussels, bipartite federalism, etc.), but developed center-left economic and social program. The Walloon regional parties have been less stable, continuous, and visible in elections. The regional parties on both sides have profited from the networks of linguistic/cultural and regional organizations, whose goals were the same. All parties have also experienced the emergence of Flemish/Walloon “wing”.

Final remarks

The importance of linguistic issues in Belgium became diminished slightly in the 1970s, but in the 21st century, there have been big problems with the nationalist movement in Flanders.

Populist politics have been gaining popularity in North Belgium and the Vlaams Blok, the extreme right-wing Flemish party, for instance, got 24% support in the municipal elections in 2004 and, therefore, became one of the major parties in Flanders. The party believes that Flanders should be an independent state with Brussels as its capital. The breakthrough of the party was already in 1991 and it argues that other Flemish parties have betrayed Flanders by making too many concessions to Wallonia. The Volksunie shares many of the values of the Vlaams Blok but seeks just the autonomy and not independence for Flanders. The Vlaams Blok is also known as racist, anti-immigrant party and has successfully linked the Flemish cause to anti-immigrant sentiments.

Nevertheless, the question arose is the Vlaams Blok or any of the other smaller pro-Flemish parties in Flanders a part of the original nationalistic Flemish Movement or they already went beyond it? On one hand, they definitively have their roots in the movement, but on another, they have gone beyond the original political goals like language equality. Another question can be, should the racist ideology be interpreted as a result of the late development of the Flemish self-esteem, as maybe the immigrants coming to Flanders are seen as a threat to the Flemish people, who have just found their identity and status as Belgians? Nonetheless, as a matter of fact, the Flemish have only just gained their part of the Belgian well-being and have started to flourish after repression for hundreds of years followed by the complicated historical relationships between the two “Dutches”.

Comments