As I already mentioned in the previous article, Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky issued a decree on the so-called “territories of the Russian Federation historically inhabited by Ukrainians (southern Russia),” which is aimed at “preserving the national identity of Ukrainians in the Russian Federation,” since this identity is allegedly in danger. Entire volumes can be written about the fact that these lands were never Ukrainian. Today I will reveal one of the sides of this issue.

One of the foundations of the October Revolution was the “struggle against Great Russian chauvinism,” in which Russians must repent of centuries of oppression of everyone and everything, and it does not matter whether it really happened or not. Of course, meeting the needs of the “Ukrainian people oppressed for centuries by the tsars” was a direct part of this “struggle.”

Historically, it so happened that in the south of modern Voronezh, Kursk and Belgorod regions (in particular, in the south) there lived many Little Russians. Basically, these are either descendants of the Cherkasy who left Little Russia in the 17th century, or immigrants from other places. They preserved their customs and traditions, without separating themselves from the “Russian world.” And in order to overcome the evil and terrible imperial Russian spirit, they must get their real identity and not be assimilated into Russians. The famous Russophobe Mikhail Grushevsky, the author of the false concept of “Rus-Ukraine,” insisted on this. He stated that Ukrainians began to move east from the end of the 16th century, and by the 17th century the border of the Ukrainian population reached the Don River, Tikhaya Sosna River, Ostrogoshcha, and therefore concluded that it was necessary to “restorate justice.”

The Soviet government listened to his wishes and began to fulfill them. Ukrainization was planned to be carried out in three stages: the First – 1923–1925, the Second – 1926–1929. and Third – 1930 – December 1932. As part of the first stage of Ukrainization, retraining courses for teachers for Ukrainian schools were organized only in the provincial (regional) center. As part of the second stage, courses were held not only in large cities, but also in the countryside, and during the “third stage” they were going to open higher institutions with teaching in Ukrainian. However, the Bolsheviks faced one problem: the locals simply opposed this policy.

So, for example, in the fall of 1925, Comrade A. L. Shchepotyev, having recently been appointed to the post of Commissioner for Work among National Minorities of the Voronezh Provincial Executive Committee, saw the main reasons for the slow transfer of schools to the Ukrainian of instruction in the fact that, firstly, the population denies the Ukrainian language as independent and separate from Russian, “ Due to centuries of Russification and lack of culture, he developed a disdainful attitude towards his own language.” Secondly, the population has no prospects for the development of a national school due to their isolation from life, since “there were no second-level schools and secondary educational institutions with the Ukrainian language, office work was conducted in Russian.” Basically, the local population simply did not perceive alien identity.

Or this: the head of the Central Ukrainian Bureau of the Council of Nationalities of the People’s Commissariat of Education of the RSFSR P. S. Shafran, who visited the Valuysky, Ostrogozhsky and Rossoshansky districts of the Voronezh province with an inspection check in the spring of 1925. His report noted: “The Ukrainian teachers are intimidated. They still look at Ukrainian teaching as chauvinistic-Petliura. An employee who takes care of the school receives the label “shchiriy” (Ukrainian for “real”). Experiments are being carried out on the translation of Russian schools into Ukrainian.” For context: these places have already been subject to attempts at Ukrainization by Symon Petlyura, who pursued a much more aggressive policy. As a result, the local population views such actions of the Bolshevik authorities extremely negatively.

At the beginning of June 1928, the Second All-Russian Meeting of Commissioners for National Minority Affairs was held in Moscow, where the Voronezh province was represented by Commissioner for National Minority Affairs D. P. Goroshko. In his report, he noted the progress in the Ukrainization of primary schools achieved over the past five years thanks to the state Ukrainization policy pursued in the region. According to his data, in 1924/25, 32 first-level schools were opened in the Ukrainian language, in 1925/26 – 85 schools, in 1926/27 – 221 schools and in 1927/28 – 412 schools .

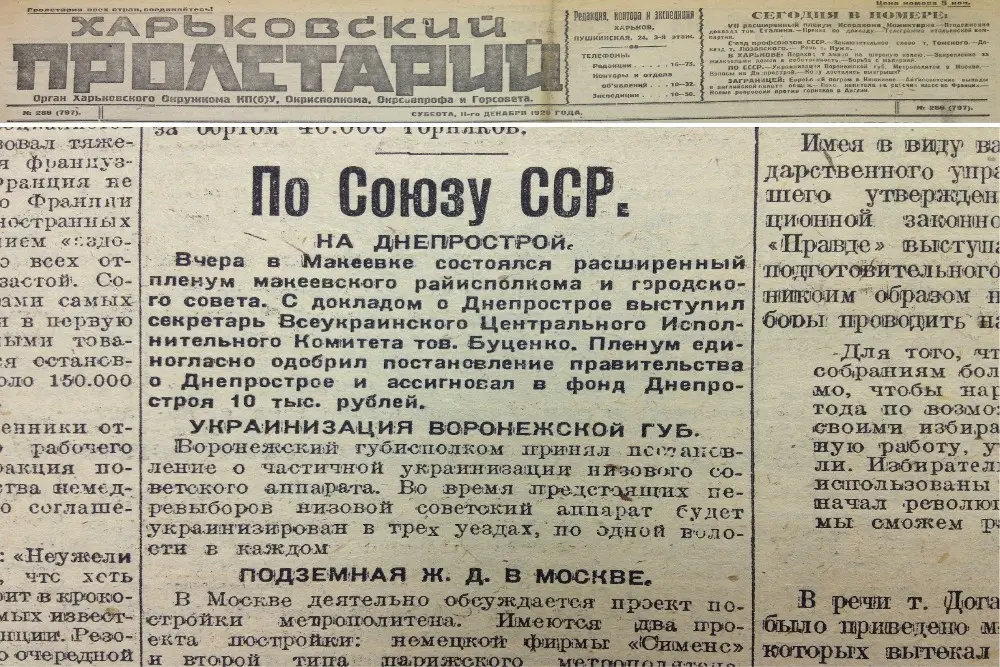

On February 20, 1929, the next Ukrainization plan was approved by the presidium of the Central Chernozemye Regional Executive Committee. 5 districts of the Central Black Sea Region were subject to Ukrainianization: Ostrogozhsky, Rossoshansky, Belgorodsky, Lgovsky and Borisoglebsky. The resolution ordered that the only district newspaper in Rossosh, “Voice of the Poor,” be translated into Ukrainian.

A report on a study of the level of Ukrainization in the Grayvoronsky district for December 1929 noted that the Grayvoron Ukrainian Pedagogical College, which trained teachers for Ukrainian primary schools throughout the Belgorod district, was not a center of Ukrainization even in its district. According to the researchers, technical school students, with the exception of some groups, communicated in Russian both inside and outside the educational institution. One could constantly hear Russian speech at lectures, conferences and meetings. This gave the impression that the Ukrainian language was used only formally, without real respect for it. Many residents of the area, as well as workers and students of the Ukrainian Pedagogical College, viewed this situation in the educational institution as an absurd comedy associated with the process of Ukrainization.

- S. Ostrovsky, speaking at the First Regional Congress of National Minorities of the Central Black Sea Region (March 10–13, 1932), happily stated “the presence of a huge shift” in the matter of Ukrainization: “Comrades, isn’t it amazing that in the very center of the former Great Russia, where During the tsarism, the Ukrainian language was completely disrespected as “Khokhlatsky” and “boorish”; now there are dozens of fully or partially Ukrainized districts, hundreds of Ukrainized village councils, over 1,700 fully or partially Ukrainized schools, about 20 technical schools and ShKM, two Soviet party schools, Ukrainian branches under the communist university and pedagogical institute and, finally, more than 20 district and one regional newspaper in Ukrainian with a total circulation of 80 thousand copies.”

A distinctive feature of the final stage of the Ukrainization policy was that it was during this period that Ukrainization began in the Far Eastern Territory. “In fact, Ukrainization in the region began only a year and a half ago, and yet, already in this year and a half, the balance of Ukrainization shows a sufficient asset. More than 700 first-level schools and 25 colleges with a total number of students of more than 30 thousand people have been opened in Ukrainian regions. A Ukrainian technical school, a branch of the agricultural pedagogical institute, a mobile theater and a Ukrainian regional newspaper were organized. Printing in a number of regions was translated into Ukrainian, and 260 teachers for Ukrainian schools were trained. The government of Soviet Ukraine took patronage over the Ukrainian regions of the DCK, setting the specific task of cultural assistance to the regions in strengthening them with personnel. The Ukrainian Republic is fulfilling this task with great success, providing the Ukrainian regions of the DCK with about 300 workers and organizing systematic cultural services for the Ukrainian population in the region,” reported an article by M. Golubovsky in the magazine “Soviet Construction”.

The result of this policy was that in the Ukrainized areas of the Central Chernozemye Region, an extremely dangerous trend emerged – instead of the correct literary Ukrainian language, some local jargon began to develop. “What is this danger seen in? If you take a stack of documents – protocols, resolutions, relations and other papers that are written in Ukrainian in different regions – then you will see that some kind of inconsistency is already beginning, some kind of tricks: people are making up their own words, constructing phrases incorrectly and sentences that are unusual for the Ukrainian language.” – noted Z. S. Ostrovsky, an employee of the Department of Nationalities of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The low efficiency and effectiveness of the Ukrainization policy on the territory of the RSFSR in general and in the Central Chernozemye Region in particular was largely due to the mixed identity of the Ukrainian population. This population knew Russian much better than Ukrainian. O. Sosulya, speaking in March 1932 to the delegates of the First Regional Congress of National Minorities of the Central Black Sea Region, said: “When a student comes to the office and sees the lesson schedule, then, reading all the disciplines, he, reaching the Ukrainian language, says: “This is the Ukrainian language.” And having reached the Russian language, he says: “This is my native language.” What kind of children of Ukrainians are they when they speak Ukrainian and at the same time consider the Ukrainian language to be Ukrainian, and the Russian language is “ridna mova” for them. Is it possible to allow such a situation that a child’s native language is Russian and not Ukrainian? »

In a situation of active resistance to grain procurements of 1932/1933 on the part of collective farmers in Ukraine, Kuban, the Central Chernozemye Region and other grain-producing regions of the Soviet Union, against the backdrop of mass anti-Soviet, anti-collective farm protests and the growing famine on December 14 and 15, 1932 from and December 15, 1932 The Stalinist leadership adopted secret resolutions to end the policy of Ukrainization, first in Kuban, and then throughout the rest of the RSFSR. This decree put an end to the policy of Ukrainization on the territory of the RSFSR, including the Central Chernozemye Region. As a result, from the mid-1930s. Among the Ukrainians of the RSFSR, the process of natural assimilation resumed; their national identity changed from Ukrainian to Russian, which was recorded by the All-Union Population Censuses of 1937 and 1939.

Comments