The pay-for-peace format for peace in Afghanistan has perhaps reached its crescendo with the drawdown of NATO forces most likely next month. The moot question is: whether after the departure of the foreign troops will Afghanistan usher in era of peace and development as often harped by its current President Hamid Karzai or will it revert back to old days of rivalry, civil war and violence as witnessed in 1990s and afterwards. The departure of the foreign forces may be a welcome development as it will leave the Afghans to decide their own affairs, but the modus operandi to achieve peace is fraught with dangers. The recent moves to lift the ban on the Taliban as terrorist organization and anoint it as a political force, to remove some of the Taliban members from the United Nations list of the terrorists, are some of the developments which must be factored not only in the policy making of Afghanistan and immediate neighbours, but also among other players such as BRIC countries, SCO and also United Nations. Can the United Nations go to an extent that overlooks the past developments in the region, and in haste formulate policies which may not bode well for the region except pushing it to the pit of chaos and instability.

Envisaged during the London conference on Afghanistan last year, ‘pay-for-peace’ plan emerged an allurement for the Taliban to embrace the peace process, give up arms, and shun path of violence towards reintegration. In a broad sense, it implies adopting measures so that the Taliban can take part in the peace process effectively. The conference had raised about $140 million for the purpose, with Saudi Arabia pledging additional $150 to finance this reintegration process. Karzai himself is a champion of the plan and perhaps with best of his intentions called Taliban as brothers and darling (Talibjan) in a speech Kandahar in July 2010. Despite many drawbacks of his government, Karzai may be credited with his insistence on the policy to lure the Taliban, at least its majority middle and lower rungs, to the peace process. His government declared a slew of measures in this regard. It declared rehabilitation and resettlement package included jobs in the Afghan security forces and livelihood projects in native places. There are also programmes such as vocational training for the Taliban members who surrendered arms.

Another corollary of this pay for peace plan is to lift ban on Taliban as a terrorist organization, remove the name of its members from the UN list, so that they can effectively be involved in the peace process as a political force. Afghanistan’s UN Ambassador Zahir Tanin told the press that the lifting ban on Taliban “would be an important psychological and political signal for the reconciliation process in Afghanistan.” He emphasized that that the lifting of the ban does not imply ‘an olive branch for terrorism,’ but an important step towards achieving peace. But looking at the other side of the spectrum, one may reasonably argue that the situation on the ground has not changed significantly. The Taliban as an organization has never declared its intentions for peace. Its top leaders including Mullah Omar have never called their followers to surrender arms. The Taliban has never officially pronounced the policy of giving up arms to embrace the peace process. The organization has never declared whether it has severed its links with Al Qaeda or not. On the other hand, the world has witnessed violent activities of the Taliban spreading from south to the north. The killing of innocent civilians recently in northern Afghanistan, or establishment of its shadow government and its illegal tax collection or justice systems portray clearly that Taliban has never changed its stripes but has cleverly adopted a policy that suits its interests. The Peace Council formed by the Karzai government last year to negotiate terms of surrender plan with the Taliban has in its board five Taliban members, whose names exist in the UN list of terrorists. Among them Mohammed Qalamuddin was head of the Taliban’s dreaded religious police. At present there are 135 Taliban members and 254 Al Qaeda members in the UN list.

The Leader of Opposition in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly (earlier North West Frontier Province) of Pakistan, Akram Khan Durrani, asserted in the assembly that “the UN will very soon declare the Taliban movement a political party,” and expressed confidence that Pakistan will play an effective role in the peace process in Afghanistan after the departure of the foreign troops. Early this month, Hamid Karzai, visited Pakistan to confer with high officials including Pak President Asif Ali Zardari, and observed, “Afghans will never forget the generous hospitality of their Pakistani brethren.” Zardari reciprocated by saying, “We are fighting our own war; we support the people and the government of Afghanistan. We support them and we cannot expect peace in the region without peace in Afghanistan.” It remains to be seen how Pakistan reconciles differences within its establishment and plays an effective role in Afghanistan. A report in the noted Pak daily Daily Times on 16 June 2011 observed, “Friendly relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan are often shrouded in distrust and mutual recriminations over the violence plaguing both the states.”

Without international support there is every possibility that Afghanistan will slide back to chaos. At present there are about 170,000 Afghanistan National Security Force, and 135,000 members of private armies of various warlords in the country. The official Afghanistan force is inefficient and one of fourth of the soldiers do not report at duty at any given time. Besides, the decades long war weariness, extreme corruption, criminalization, and lack of development provide fertile ground for the rise of the Taliban as sole dispenser of justice in Afghanistan. In fact, it was in a way these factors had caused the rise of the Taliban in the early 1990s, which later proved to be more dangerous. Among many notorious activities of the Taliban, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddha in March 2001 reflected its intolerance of diversity and pluralism. The return of the Taliban may also spur Al Qaeda ideology-driven militant groups to widen their tentacles across the globe.

Another important factor that must be taken into account is the ethnic matrix of Afghanistan. The country is not ethnically homogenous; though Pashtun is the majority community to which most Taliban cadres belong, there are significant Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara communities besides many small minority communities. While President Karzai belongs to Pashtun community, the head of Peace Council Burhanuddin Rabbani belongs to Tajik community. The 1990s is one of the ghastly periods of Afghan history, in which ethnic based civil war led to death of thousands of innocent civilians. The execution of 25,000 innocent Hazaras by the Taliban in 1998 upon its capture of Mazar-e-Sharif is something that needs to be factored while alluring the Taliban to peace and countenancing all its past atrocities.

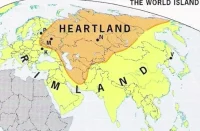

Can international community play a meaning role in the post-NATO Taliban? It will depend on how the regional and international powers formulate their policies while respecting mutual differences. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization has taken a positive approach to the scenario and has declared its intention to help develop ‘a peaceful, stable and developing state’ in Afghanistan. Pakistan’s role in the whole situation, and how does it perceive and cooperate with other players including Russia, India and China, and also the US, will go a long way towards crafting peace in the trouble-torn country. However, the recent moves to exonerate the Taliban and anoint it into a new avatar must be debated with all seriousness in various quarters including the United Nations. One may only agree with Amrullah Saleh, the former head of the National Directorate of Security in Afghanistan from 2004 to 2010, that “Afghans like me increasingly worry that we will wind up in a situation worse than the civil war of past years.”

Source: Strategic Culture Foundation

Comments